When you look at pictures of New York in 1800s, you probably expect a black-and-white version of the modern skyline. Maybe some horses? Some top hats? Honestly, the reality caught in those early daguerreotypes and gelatin silver prints is way grittier—and more chaotic—than the romanticized versions we see in period dramas. It wasn’t just a city in transition; it was a city that was basically a massive, muddy construction site for about eighty years straight.

Photography itself was a baby back then. When Louis Daguerre’s process hit the scene in 1839, the city was already a bustling hub of over 300,000 people. But if you look at the earliest shots, the streets look eerie. They’re empty. That isn't because the city was quiet; it’s because the exposure times were so incredibly long that moving people and carriages simply blurred into nothingness. You’ve got these crisp images of buildings like the Astor House, but the "life" of the city is a ghost. It’s a weird paradox. The more crowded the city got, the harder it was for early tech to actually see the people.

📖 Related: 6 foot 9 in inches: Why This Specific Height Changes Everything

The Gritty Reality of Early Manhattan Photography

Most people think of the 19th century through the lens of the "Gilded Age," but the pictures of New York in 1800s captured by folks like Jacob Riis tell a much darker, more honest story. If you’ve ever seen his work in How the Other Half Lives, you know what I mean. He wasn't just taking photos; he was using a brand-new, terrifyingly bright magnesium flash powder to expose the conditions in the Five Points slums.

The air was thick. Coal smoke from thousands of chimneys created a constant haze that photographers had to fight against. And the streets? They were genuinely disgusting. Before the "White Wings" (the city’s first real street cleaners under George E. Waring Jr. in the 1890s), the ground was a cocktail of horse manure, household trash, and mud. When you look at high-res scans of old street photography, look at the bottom of the frame. You’ll see the filth. It’s a detail most history books gloss over because it’s not particularly "majestic."

The Vanishing Architecture of the Mid-1800s

New York has this habit of eating its own history. We have photos of the Crystal Palace—a massive iron and glass structure that sat where Bryant Park is now. It was a marvel. It burned down in 1858, just five years after it opened. If it weren't for the early photographers who hauled their heavy glass plates out there, we’d only have sketches to go on.

📖 Related: Princess decorations for room: Why the plastic pink aesthetic is finally dying

Then there’s the Croton Distributing Reservoir. This was a literal Egyptian-style fortress where the New York Public Library stands today. It had 50-foot thick walls. People used to walk along the top of it for fun on Sunday afternoons. Seeing pictures of New York in 1800s featuring this massive stone monolith in the middle of Midtown feels like looking at an alternate dimension. It reminds you that the city we see today is just the latest layer of a very messy palimpsest.

How Technology Changed the Way We See the 19th Century

You can't talk about these images without talking about the gear. Early photographers were basically chemists and weightlifters. They had to carry mobile darkrooms. Imagine trying to navigate a horse-drawn cart through the chaos of Broadway just to take one photo.

- The Daguerreotype Era (1840s-1850s): These are one-of-a-kind images on silvered copper plates. They have a depth that modern digital photos still can't quite replicate.

- Stereographs: These were the 19th-century version of VR. You’d have two slightly different images side-by-side, and when viewed through a special device, the city jumped out in 3D. Millions of these were sold. It was the first time people in rural America could "see" the scale of the Brooklyn Bridge.

- Dry Plate Photography: This was the game-changer in the 1880s. It allowed for faster shutter speeds. Suddenly, the "ghosts" were gone. We started seeing the blur of a moving trolley and the candid expressions of street urchins.

The transition from posed, stiff portraits to "detective camera" shots (early hidden cameras) meant we finally got to see New Yorkers as they actually were: hurried, annoyed, and intensely busy.

The Mystery of the "Missing" Skyscrapers

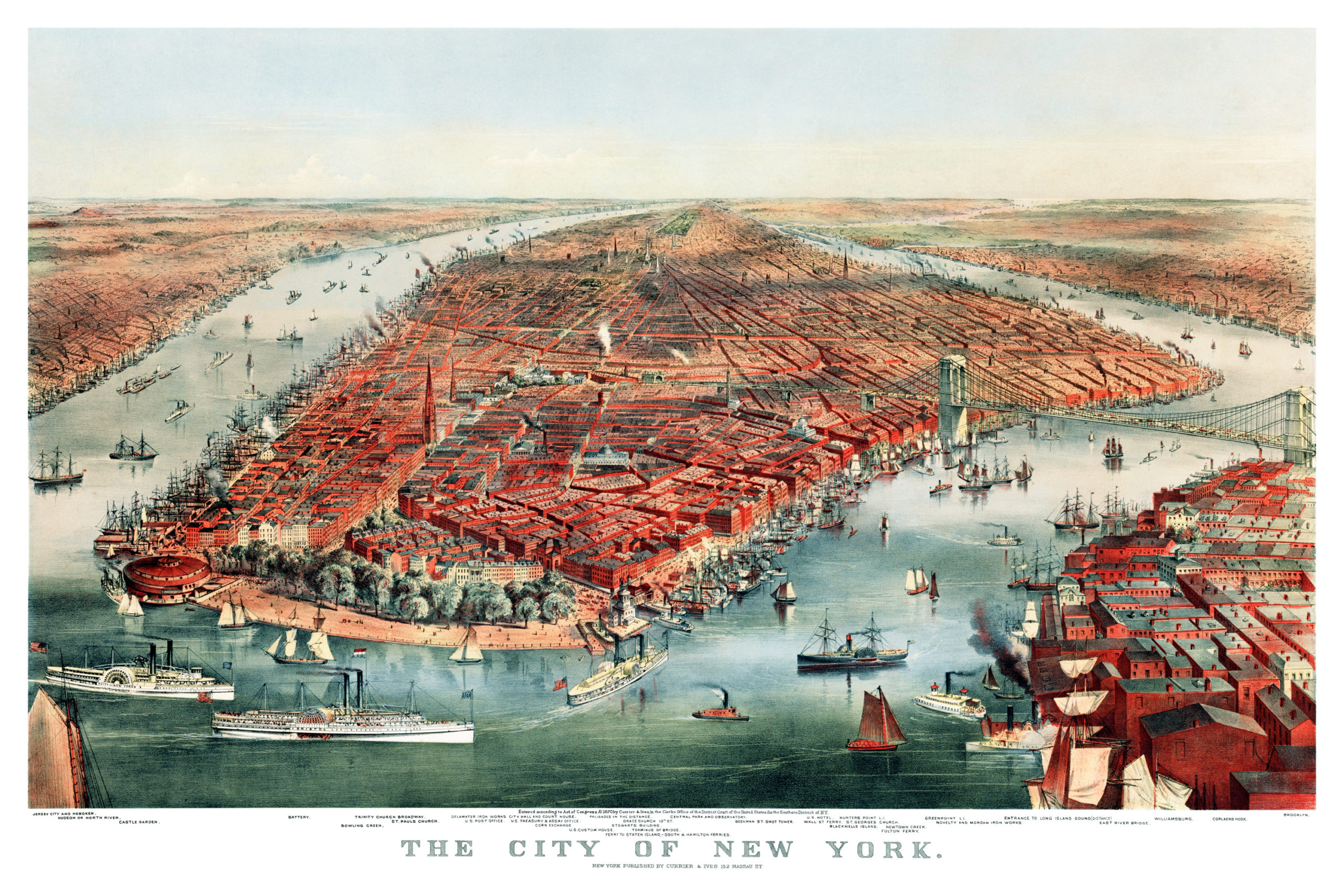

A common mistake people make when browsing pictures of New York in 1800s is looking for the skyline. It didn't exist yet. Until the very end of the century, the tallest things in the city were church steeples. Trinity Church dominated the view. It wasn't until the Tower Building in 1889 that the "vertical" race really started. If you see a photo with a massive skyline, it’s likely from 1905 or later, regardless of what the caption says.

The scale of the 1800s was horizontal. The city was creeping northward, past 42nd Street, devouring farms and rocky outcrops. Central Park was a massive engineering project that involved more gunpowder than the Battle of Gettysburg just to clear the terrain. Photos from the 1860s show the park as a barren, muddy wasteland—not the lush oasis we know.

Practical Ways to Verify and Explore These Images

If you’re hunting for authentic pictures of New York in 1800s, don't just trust a random Pinterest board. People misdate photos constantly. A "1850s" photo showing a skyscraper is a lie. A "1870s" photo showing the Statue of Liberty is also a lie (she wasn't fully assembled until 1886).

- Check the New York Public Library (NYPL) Digital Collections. They have the "Digital Schomburg" and the Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views. This is the gold standard.

- Look for the "OldNYC" map tool. It’s a fan-made project that pins NYPL photos to their actual geographic locations. You can "walk" down a street in 1875.

- Study the lighting. Early photos relied heavily on natural light. If a photo looks perfectly lit in a dark alleyway in the 1860s, it might be a later recreation or a highly edited print.

- Identify the transit. The presence of "El" (elevated) trains tells you you’re looking at 1870 or later. Horse-drawn omnibuses were the kings of the road before that.

The best way to truly experience these images is to look at the high-resolution "Tiff" files. Zoom in. Look at the signs in the windows. Look at the posters for long-forgotten theater shows. That’s where the real New York lives—in the tiny, accidental details that the photographer didn't even know they were capturing.

To get started on your own archival journey, head over to the Library of Congress website and search for the "Detroit Publishing Company" collection. They hold some of the clearest glass-plate negatives ever produced of the late 1800s. Download a high-res copy of a Broadway street scene from 1890 and spend ten minutes just looking at the faces of the people in the background. You'll realize they weren't that different from us; they were just navigating a much louder, smellier, and faster-changing world. Don't just look at the buildings—look at the life between them.