You’ve seen them. Those ethereal, cascading clusters of pearly white or soft grey shelf-like fungi growing out of a decaying log in a misty forest. Or maybe you've scrolled past a high-contrast studio shot of a "Pink Flamingo" oyster mushroom looking more like a tropical flower than something you’d sauté with garlic and butter. Pictures of oyster mushrooms are everywhere lately—from cottagecore Pinterest boards to high-end culinary blogs—but there is a massive gap between a pretty photo and what these fungi actually represent in the wild or on your plate.

Most people look at a photo and think "dinner." Experts look at those same images and see a complex network of mycelium that is literally digesting the world around it.

The Pleurotus genus is actually one of the most resilient and fascinating groups of fungi on the planet. They aren't just passive decomposers. Did you know they’re carnivorous? Yeah, for real. While you’re admiring the delicate gills in a close-up shot, that mushroom is busy secreting toxins to paralyze microscopic nematodes (roundworms) in the soil, digesting them to get the nitrogen it needs to grow. It’s a brutal, tiny world out there, and the pictures rarely capture that predatory edge.

Identifying What You See in Pictures of Oyster Mushrooms

When you’re looking at a photo, how do you even know it's a real oyster? You have to look at the gills. On a true Pleurotus ostreatus, the gills are "decurrent." That’s a fancy mycological way of saying they run all the way down the stem, often tapering off into the wood or substrate. If the gills stop abruptly at the top of the stalk, you’re looking at something else. Maybe a poisonous Look-alike like the Jack O'Lantern mushroom (Omphalotus olearius), which can cause some serious gastrointestinal distress, though it usually glows in the dark—which is a cool trick, just not one you want in your frying pan.

📖 Related: Other Words for Assassin: Beyond the Hollywood Hitman

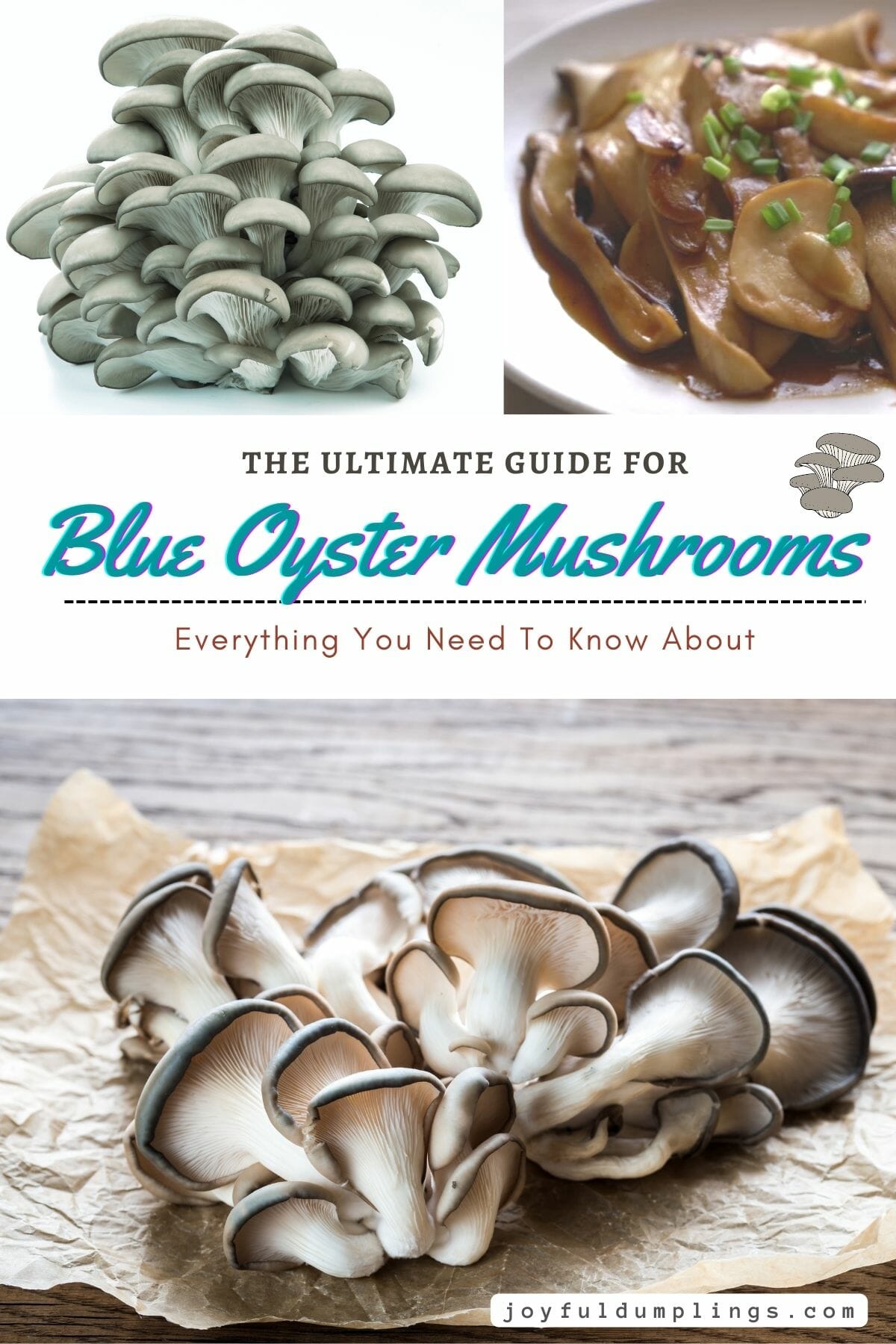

Color is another thing that trips people up. In professional pictures of oyster mushrooms, you'll see vibrant blues, startling yellows, and deep browns. These aren't filters. The Blue Oyster (Pleurotus columbinus) actually thrives in cooler temperatures, and that steely blue hue is a reaction to the environment. If it gets too warm, that blue fades into a dull grey. Then you have the Golden Oyster (Pleurotus citrinopileatus), which is stunningly bright yellow but has become a bit of a controversial figure in North American forests. It’s an escaped cultivar from Asia that is now spreading aggressively through the wild, outcompeting native species. So, a beautiful photo of a yellow cluster in a Wisconsin forest is actually a snapshot of an ecological shift in progress.

The Problem With Commercial Stock Photos

If you search for stock imagery, you’ll often find "perfect" specimens. They’re clean, symmetrical, and usually sitting on a white background. Honestly, these are the least helpful images if you’re trying to learn about the species.

In reality, wild oysters are often covered in little black beetles or have bits of bark embedded in the cap. They grow in overlapping shelves, often so thick you can’t see the wood behind them. A "perfect" mushroom is usually a lab-grown one. Commercial growers use bags of pasteurized straw or sawdust blocks to get those uniform shapes. When you see a picture of a mushroom that looks like a bouquet of roses, it likely came from a climate-controlled grow tent where the CO2 levels were meticulously managed to encourage the caps to spread wide rather than growing long, "leggy" stems.

Why Quality Images Matter for Foragers and Cultivators

For the amateur forager, a high-resolution photo is a lifeline. But it’s also a trap. You cannot—and I mean never—rely solely on a picture for identification. You need to feel the texture. You need to smell it. Oyster mushrooms have a very specific scent that many describe as slightly sweet, almost like anise or black licorice. Some people just think they smell like fresh mushrooms, but that faint hint of sweetness is a key field mark.

📖 Related: Why 1232 Ridge Ave Evanston IL 60202 Stays on the Radar for Local Real Estate

If you're looking at photos to decide whether to pick something, pay attention to the substrate. Oyster mushrooms are saprotrophic, meaning they eat dead or dying wood. If you see a "mushroom that looks like an oyster" growing directly out of the soil with no wood nearby, walk away. It might be a Hohenbuehelia, or something even more obscure.

Cultivators use photos for a different reason: contamination checks. A "good" picture of an oyster mushroom colony in a grow bag should show pure white, fuzzy mycelium. If the photo shows even a hint of green or "bread mold" black, the whole batch is toast. Experts like Paul Stamets have spent decades documenting these growth patterns, and his books are filled with the kind of gritty, technical photos that show the ugly side of mushroom farming—the molds, the "weeping" metabolites, and the distorted growth.

Decoding the Different Species

It’s easy to think an oyster is just an oyster. It isn’t.

- Pearl Oysters (Pleurotus ostreatus): These are the ones you see most in grocery stores. They have a mild, nutty flavor and a brownish-grey cap.

- King Oysters (Pleurotus eryngii): These look nothing like the others. They have tiny caps and massive, thick stems. If you see a picture of sliced "scallops" made from mushrooms, it's these guys. They are the giants of the family.

- Pink Oysters (Pleurotus djamor): These are incredibly photogenic but very temperamental. They love heat and will actually die if you put them in a standard refrigerator. Their vibrant pink color usually fades to a light peach or white once they’re cooked.

The Art of Mushroom Photography

Taking a good photo of a fungus is harder than it looks. You’re usually on your hands and knees in the mud. To get those "hero shots" you see in National Geographic or high-end foraging blogs, photographers use small mirrors to bounce light up into the gills. This reveals the structural complexity that makes these organisms so efficient at shedding spores.

A single oyster mushroom can release billions of spores. In some indoor farm photos, you can actually see a fine white dust coating everything nearby. That’s not dust; it’s the mushroom’s "offspring." This is why commercial growers have to wear respirators. Breathing in that many spores can lead to "mushroom worker's lung," an allergic reaction that’s as unpleasant as it sounds.

When you look at pictures of oyster mushrooms through this lens, they stop being just pretty objects. They are biological engines. They are recyclers. They are, in a very literal sense, the lungs of the forest floor, breaking down tough lignin and cellulose that other organisms can't touch, turning old trees into new soil.

Modern Uses and Environmental Impact

Beyond the plate, oyster mushrooms are being photographed in labs for some pretty wild reasons. Mycoremediation is the big one. There are famous photos of oyster mushrooms growing out of piles of oil-soaked soil. Because they are so aggressive and produce powerful enzymes, they can actually break down complex hydrocarbons (oil and plastic) and turn them into non-toxic organic matter.

We’re also seeing them used in "myco-fabrication." Companies are grown-modeling furniture, packaging, and even vegan leather out of oyster mushroom mycelium. In these photos, you don't even see the mushroom cap. You just see a dense, white, brick-like material that is biodegradable and stronger than some plastics. It’s a complete reimagining of what a "mushroom" can be.

How to Use This Information Today

If you’re interested in these fungi, don't just look at the pictures. Start by observing the real thing. Go to a local farmer’s market and buy a cluster. Look at how the gills join the stem. Feel the slightly tacky texture of the cap.

If you want to take your own photos, get low. Use a macro lens if you have one, or just the "portrait" mode on your phone to blur the background and make those gill structures pop. But remember, the photo is just a flat representation of a three-dimensional, living, breathing (literally!) organism.

For those looking to get into foraging, join a local mycological society. There is no substitute for an expert standing next to you, pointing at a log, and explaining why that specific cluster is safe and the one ten feet away isn't. Use books like "All That the Rain Promises and More" by David Arora—it’s full of great, quirky photos that give a much better sense of the mushroom’s "personality" than a sterile stock image ever could.

Final Practical Steps

- Check the Substrate: Always note if the mushroom is on wood (correct) or dirt (suspicious).

- Inspect the Gills: Look for that "decurrent" pattern where the gills run down the stem.

- Verify the Spore Print: If you’re unsure, take a cap and leave it gills-down on a piece of dark paper overnight. Oyster mushrooms should leave a white to lilac-grey spore print.

- Store Properly: If you’ve bought or foraged some, never store them in plastic. They need to breathe. Use a paper bag. Plastic turns them into a slimy mess within 24 hours.

Understanding the reality behind pictures of oyster mushrooms makes the images themselves much more rewarding. You aren't just looking at a plant—mostly because they aren't plants at all—you're looking at one of nature's most sophisticated survivalists. Whether they're cleaning up an oil spill or just making your pasta taste better, they deserve a closer look than a quick scroll-by.