He isn't always wearing red. He doesn't always have a giant, snowy beard that looks like a marshmallow. Honestly, if you saw some of the earliest pictures of St Nicholas, you might not even recognize him as the guy who supposedly slides down your chimney every December.

We’ve spent centuries sanitizing the image of a 4th-century Greek bishop from Myra (modern-day Turkey). Today, we have the Coca-Cola version. But the real history? It’s written in gold leaf, jagged Byzantine mosaics, and even forensic facial reconstructions that might make you do a double-take.

💡 You might also like: Years of Ox Chinese Zodiac: Why Your Birth Year Is More Than Just a Cow

The Evolution of the Image

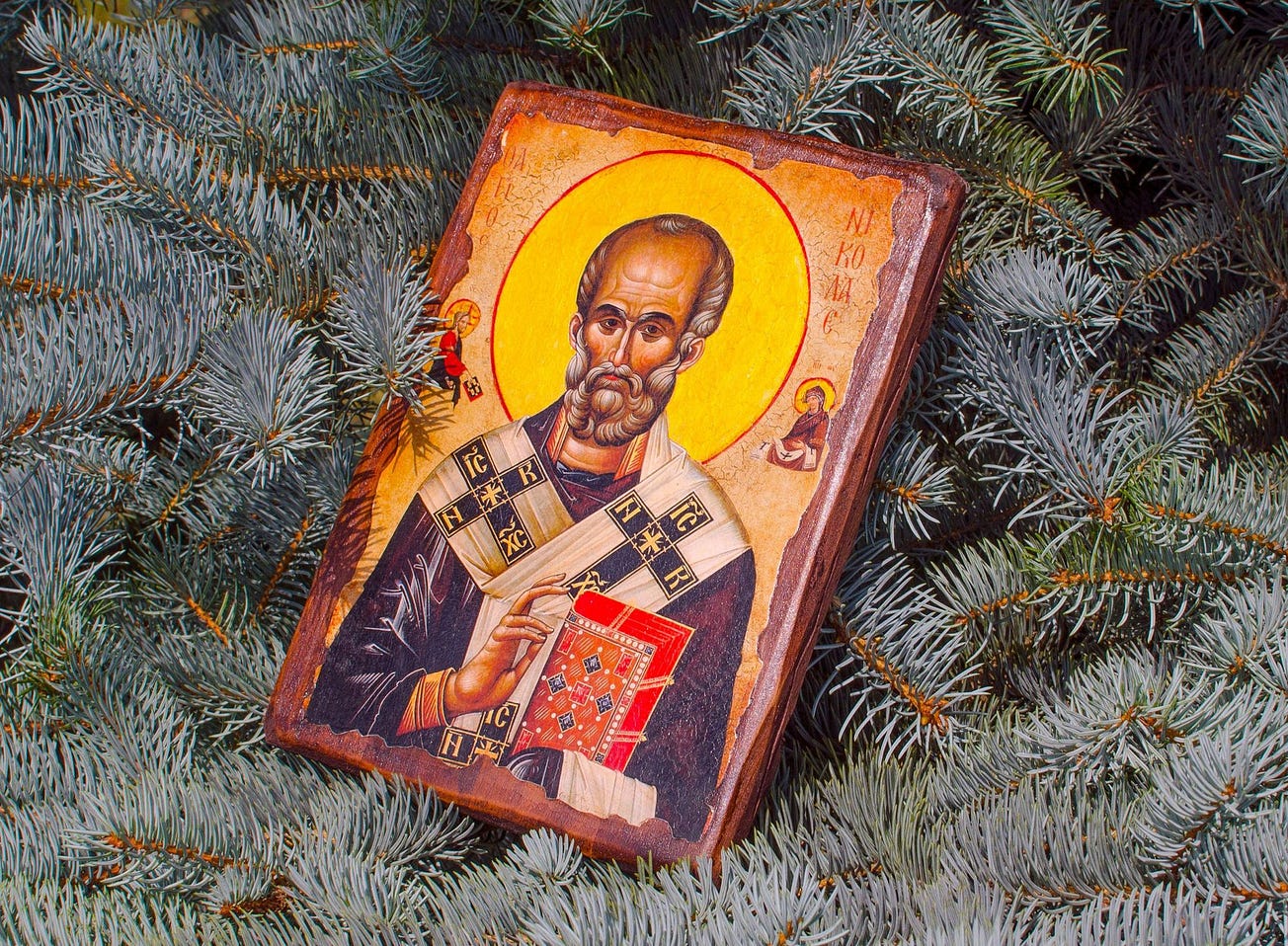

The earliest depictions of Nicholas of Myra aren't "jolly." Not even close. If you look at the 11th-century mosaics in the Hosios Loukas monastery in Greece, you see a man who looks serious. Grave, even.

He’s thin. His forehead is high and balding. He’s wearing the omophorion—that long, white silk scarf decorated with crosses that signifies his rank as a bishop. There is no fur trim. There is no velvet.

For a long time, the way we viewed pictures of St Nicholas was dictated entirely by the Eastern Orthodox tradition. These icons weren't meant to be "realistic" portraits in the modern sense. They were windows into the divine. Artists used specific color palettes—ochre for the skin, deep blues or reds for the robes—to convey spiritual authority rather than physical likeness.

But then things got weird in the West.

When his relics were stolen—or "translated," depending on who you ask—and taken to Bari, Italy, in 1087, the imagery started to shift. Western artists began adding flair. They started including the "Three Gold Balls" or the three bags of gold he supposedly tossed through a window to save a poor man's daughters from a life of destitution.

Why his face looks different in every century

It’s all about the audience. In the Middle Ages, people needed a protector. They needed a saint who could stop shipwrecks and bring children back to life (yes, there's a wild legend about three pickled boys—look it up). Consequently, the art reflected that power.

By the time we get to the Dutch Sinterklaas, he’s starting to look a bit more like a tall, regal figure on a white horse. But he’s still a bishop. He’s still wearing the miter (the tall, pointy hat).

What science says he actually looked like

In 2004, a facial reconstructive surgeon named Dr. Caroline Wilkinson used data from the saint’s actual bones in Bari to create a digital model of his face. This is probably the most accurate "picture" we will ever have.

The result?

He had a broken nose.

Seriously. The skull showed a nose that had been badly broken and healed crookedly. This fits with historical records of the persecution of Christians under Emperor Diocletian. Nicholas was likely imprisoned and beaten for his faith. He wasn't a soft, round man; he was a tough, weathered survivor with olive skin and a square jaw.

- Height: Roughly 5 feet 6 inches.

- Physicality: Lean, not overweight.

- Complexion: Typical for someone of Middle Eastern or Mediterranean descent.

Seeing these forensic pictures of St Nicholas side-by-side with a modern mall Santa is jarring. We’ve traded a gritty, persecuted bishop for a guy who promotes sugary soda.

The Thomas Nast Turning Point

If you want to know when the "pictures" changed forever, you have to look at the American Civil War era. A political cartoonist named Thomas Nast is largely responsible for the visual shift.

Nast took the Dutch Sinterklaas and the German Pelznickel and mashed them together. For Harper’s Weekly, he drew a rotund, bearded man in a suit covered in stars and stripes.

Suddenly, the bishop’s miter was gone. The robes were replaced by a wooly suit.

Later, in the 1930s, illustrator Haddon Sundblom refined this for Coca-Cola. He used his friend, a retired salesman named Lou Prentiss, as a model. This is why modern pictures of St Nicholas look like a friendly grandpa. It was a marketing masterstroke that effectively erased 1,500 years of ecclesiastical art from the public's collective memory.

Real examples you can still see today

If you’re a history nerd, don't settle for the cartoon version. Check out these specific pieces of art:

- The Basilica di San Nicola in Bari: You can see icons that have been venerated for nearly a millennium. They feel heavy with incense and history.

- St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai: They house some of the oldest surviving icons in the world. The 13th-century Nicholas icons here show the transition from the "holy man" to the "global saint."

- Russian Icons: Russia loves Nicholas. Their "Nikola" icons often show him flanked by Jesus and Mary, emphasizing his status as an intercessor. These are characterized by incredibly fine detail in the beard—almost like wire work.

Misconceptions about the "Red Suit"

Everyone says Coca-Cola invented the red suit.

That’s actually a myth.

While they certainly standardized it, pictures of St Nicholas as a bishop often featured red because red was (and is) a liturgical color of the Church. It represented the blood of Christ and the authority of the office. Nast’s early drawings were sometimes in green or tan, but red was already a dominant theme in the 1800s.

It’s just that the red went from "sacred vestment" to "pajama suit" over about fifty years.

Why we still care about these images

Visuals matter because they tell us what we value. When we look at the original Byzantine pictures of St Nicholas, we see a man defined by his scars and his service. When we look at modern versions, we see a man defined by his generosity and his joy.

Both have their place.

But understanding the "real" face helps ground the legend. It reminds us that behind the flying reindeer and the North Pole workshop, there was a real person living in a turbulent time who chose to give away what he had.

If you're looking for authentic depictions, search for "Hodegetria style Nicholas" or "Byzantine hagiographical icons." You'll find scenes of him saving sailors from storms or secretly dropping coins into shoes. These narrative pictures tell a much deeper story than a greeting card ever could.

Actionable ways to explore the history

To truly appreciate the visual history, don't just scroll through Google Images. Try these steps:

- Visit a local Orthodox church. Most will have an icon of St. Nicholas on the iconostasis (the wall of icons). Look at the specific hand gestures—usually, he’s holding a Gospel book and giving a blessing.

- Compare the forensic model. Look up the University of Dundee's 2014 updated facial reconstruction. It uses more advanced tissue depth data than the 2004 version and gives a hauntingly real look at the man.

- Trace the symbols. When looking at old art, identify the "attributes." If you see three gold balls, a ship, or an anchor, you're definitely looking at Nicholas.

- Check out the "Boy Bishop" art. In the Middle Ages, it was common to see pictures of children dressed as Nicholas, a tradition that flipped the hierarchy for a day.

The "real" Nicholas is more complex, more Mediterranean, and way more interesting than the caricature. Seeing him through the lens of history doesn't ruin the magic; it just adds a whole lot of soul to the story.

Practical Research Note: For those diving deep into art history, the "Index of Medieval Art" at Princeton University is the gold standard for finding authenticated, tagged pictures of St Nicholas from the first millennium. It’s a bit clunky to use, but the data is unmatched for accuracy.