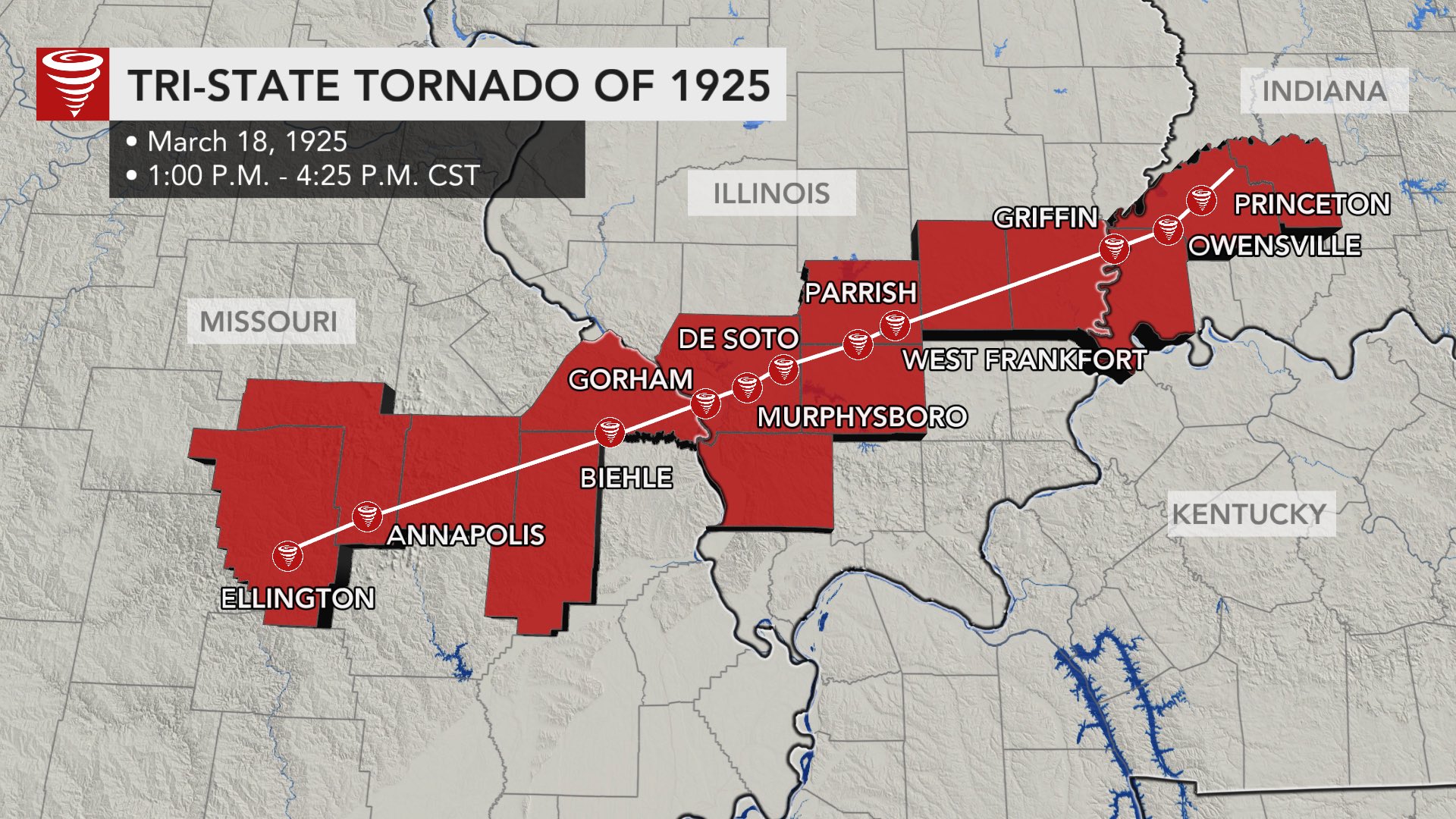

March 18, 1925. It started as a relatively small "puff" near Ellington, Missouri. Nobody knew it would become the deadliest tornado in American history. By the time it finally dissipated in Indiana three hours later, 695 people were dead. Thousands more were injured. Whole towns like Murphysboro and West Frankfort were basically wiped off the map. If this happened today, we’d have thousands of 4K videos on TikTok within minutes. But back then? Getting pictures of the tri state tornado was a logistical nightmare.

Photography in 1925 wasn't just "point and shoot." You had heavy box cameras, glass plates or early film rolls, and a total lack of warning. When a monster is moving at 70 miles per hour, you don't stand around adjusting your tripod. You run.

Most of what we have left are the "after" shots. The ruins. The debris fields. But looking at these photos tells a deeper story than just structural failure. They show a level of violence that even modern meteorologists struggle to fully wrap their heads around.

The Mystery of the Missing Funnel Cloud Photos

You might have seen a few grainy images online claiming to be the actual funnel. Most of them are fakes or photos of other storms. Honestly, there are almost zero confirmed, clear pictures of the tri state tornado while it was on the ground as a funnel. Why? Because it didn't look like a classic Kansas twister.

Eyewitnesses described it as a "low-hanging fog" or a "boiling carpet of clouds." It was a massive, wedge-shaped monster. It was so wide—sometimes over a mile—and shrouded in so much dust and debris that people didn't even realize it was a tornado until it was on top of them. Imagine seeing a wall of black clouds moving toward you at highway speeds. You wouldn't think "tornado," you'd think "dark thunderstorm."

By the time the realization hit, it was too late to set up a Kodak Brownie camera.

The few blurry images that exist of the "storm cloud" itself show a dark, indistinct mass. One of the most famous shots, often attributed to the 1925 event, shows a dark wall of cloud near Murphysboro, but even its authenticity is debated by weather historians. Most photographers were too busy dying or hiding in fruit cellars to capture the "money shot" we expect in the age of storm chasing.

What the Destruction Photos Reveal About F5 Intensity

The real archive of pictures of the tri state tornado starts in the hours and days following the disaster. These aren't just photos of broken windows. We are talking about "clean sweeping."

In places like Griffin, Indiana, the photos show foundations that were literally scrubbed clean. No wood. No bricks. Nothing. This is what meteorologists today use to categorize an EF5. When you see a photograph from 1925 showing a heavy machinery plant in Murphysboro reduced to a pile of twisted iron, you're looking at wind speeds that likely exceeded 300 miles per hour.

📖 Related: That Viral Video of a Deobra Redden Jumping at Judge Mary Kay Holthus: What Actually Happened

Specific photos archived by the Illinois State Historical Library show:

- Trees stripped of their bark. This happens when the wind is so fast it literally sandblasts the organic material off the trunk.

- Railroad tracks pulled right out of the ground.

- Household items, like delicate China plates, found miles away, completely unbroken, while the house they were in was pulverized into dust.

It’s the randomness that’s haunting. One photo shows a car wrapped around a tree like a piece of tin foil. Another shows a single wall standing in a neighborhood where every other structure is gone.

The Human Element in the Aftermath

We often focus on the "weather" part, but the photography of the era captured something much grittier. The Red Cross and local newspapers took hundreds of shots of the relief efforts. You see men in wool suits and fedoras digging through mountains of splintered lumber. You see women in long dresses standing in front of what used to be their kitchens.

These photos were used for more than just news. They were evidence. Because there was no such thing as "storm surge" or "radar signatures" back then, these pictures were the only way the rest of the country could understand the scale of the tragedy.

✨ Don't miss: Getting the Clima de 10 días para Iowa Right Without the Guesswork

Take a look at the photos from the Longfellow School in Murphysboro. It’s one of the most heartbreaking images in the collection. A massive brick building, collapsed. Seventeen children died there. The photo shows the sheer weight of the debris. It wasn't just wind; it was the pressure. The school's collapse sparked a massive shift in how public buildings were constructed in the Midwest, though that change took decades to fully realize.

Why We Still Study These Photos

Modern researchers at the NOAA and the National Weather Service still look at these old black-and-white prints. They use them for "forensic meteorology." By looking at the direction the trees fell in a 100-year-old photo, they can determine the rotation of the vortex. By looking at how a brick wall crumbled, they can estimate the forward speed of the storm.

Tom Grazulis, a renowned tornado historian, has spent years verifying these accounts. The photos confirm that this wasn't just one "lucky" strike. It was a sustained, high-intensity event that maintained F5 (on the old scale) strength for an unheard-of amount of time.

Spotting the Fakes

If you search for pictures of the tri state tornado, you’re going to find some stuff that just isn't real.

- The 1915 Sanford, Kansas Photo: This is a classic, very clear funnel cloud. It’s often used as a thumbnail for Tri-State Tornado videos. It's not the 1925 storm.

- The AI Recreations: Lately, "colorized" and "enhanced" versions have popped up. Be careful. These often "hallucinate" details like modern power lines or specific types of cars that didn't exist in 1925.

- The El Reno Overlays: Sometimes people take modern "wedge" tornado photos and put a black-and-white filter on them. If the photo looks too good to be true, it probably is.

True 1925 photos have a specific grain. They have a flat depth of field. Most importantly, they show 1920s-era infrastructure—Model Ts, specific brickwork, and period-correct clothing.

The Practical Legacy of the 1925 Archive

What do we do with this information? It’s not just a history lesson. These photos are a reminder of what a "worst-case scenario" looks like. They paved the way for the development of the first tornado warning systems. Back in 1925, the word "tornado" was actually banned from weather forecasts because the government didn't want to cause a panic. After the photos of the Tri-State disaster hit the national papers, that policy started to crumble.

People realized that the "panic" caused by a warning was nothing compared to the slaughter caused by silence.

💡 You might also like: Shanty Town: What the Definition Actually Means for Global Cities

If you want to see the real deal, don't just rely on a Google Image search. Go to the digital archives of the Southern Illinois University Carbondale or the Missouri Historical Society. They have the original scans of the post-disaster glass plates. They are high-resolution, haunting, and 100% authentic.

Actionable Steps for Historians and Weather Enthusiasts

- Verify the Source: Before sharing a photo of the Tri-State Tornado, check if it’s from a verified museum archive like the Illinois State Historical Library. If it’s from a random "spooky facts" Twitter account, it’s probably a different storm.

- Study the Debris, Not Just the Funnel: To understand the power of an F5, look at the ground. Look for "ground scouring"—where the grass itself has been ripped out. That’s the hallmark of the 1925 event.

- Visit the Memorials: Towns like Annapolis, Missouri, and Princeton, Indiana, have local museums with physical copies of these photos that aren't available online. Seeing the "death map" and the corresponding photos in person provides a scale that a screen just can't match.

- Support Digital Archiving: Many of these 100-year-old photos are deteriorating. Supporting local historical societies in the Tri-State area (Missouri, Illinois, Indiana) helps ensure these visual records are digitized for the next century.

The Tri-State Tornado remains a benchmark. It is the ceiling of what we think a storm can do. And while we lack the "action shots" we have for modern storms, the silent, still images of the aftermath say more than a video ever could. They remind us that nature doesn't care about our buildings, our schools, or our plans. It just moves.