It is only two minutes long. Actually, it's shorter—one minute and fifty seconds of acoustic yearning that has somehow managed to outlive the decade, the band, and arguably the relevance of the genre it helped define. When The Smiths released Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want in 1984, it wasn't even a lead single. It was a B-side. It was tucked away on the back of the "William, It Was Really Nothing" 12-inch, almost like an afterthought or a secret.

Music doesn't usually work this way.

Usually, the songs that define generations are anthems. They have massive choruses and pyrotechnics. But this song is different because it feels like a bruise. It’s quiet. It’s desperate. Morrissey’s vocals are stripped of his usual playful irony, leaving only a raw, almost childlike demand for fairness in a world that rarely provides it. People call it "mopey," but that's a lazy take. It’s actually a masterclass in brevity and emotional precision.

The Anatomy of a Two-Minute Masterpiece

Johnny Marr didn’t want to write a long song. He knew exactly what he was doing. He wanted something that captured a specific, fleeting feeling—that moment where you’re so tired of being disappointed that you’ve run out of clever things to say. He wrote the music on a whim, and when he played it for Morrissey, the lyrics came almost instantly.

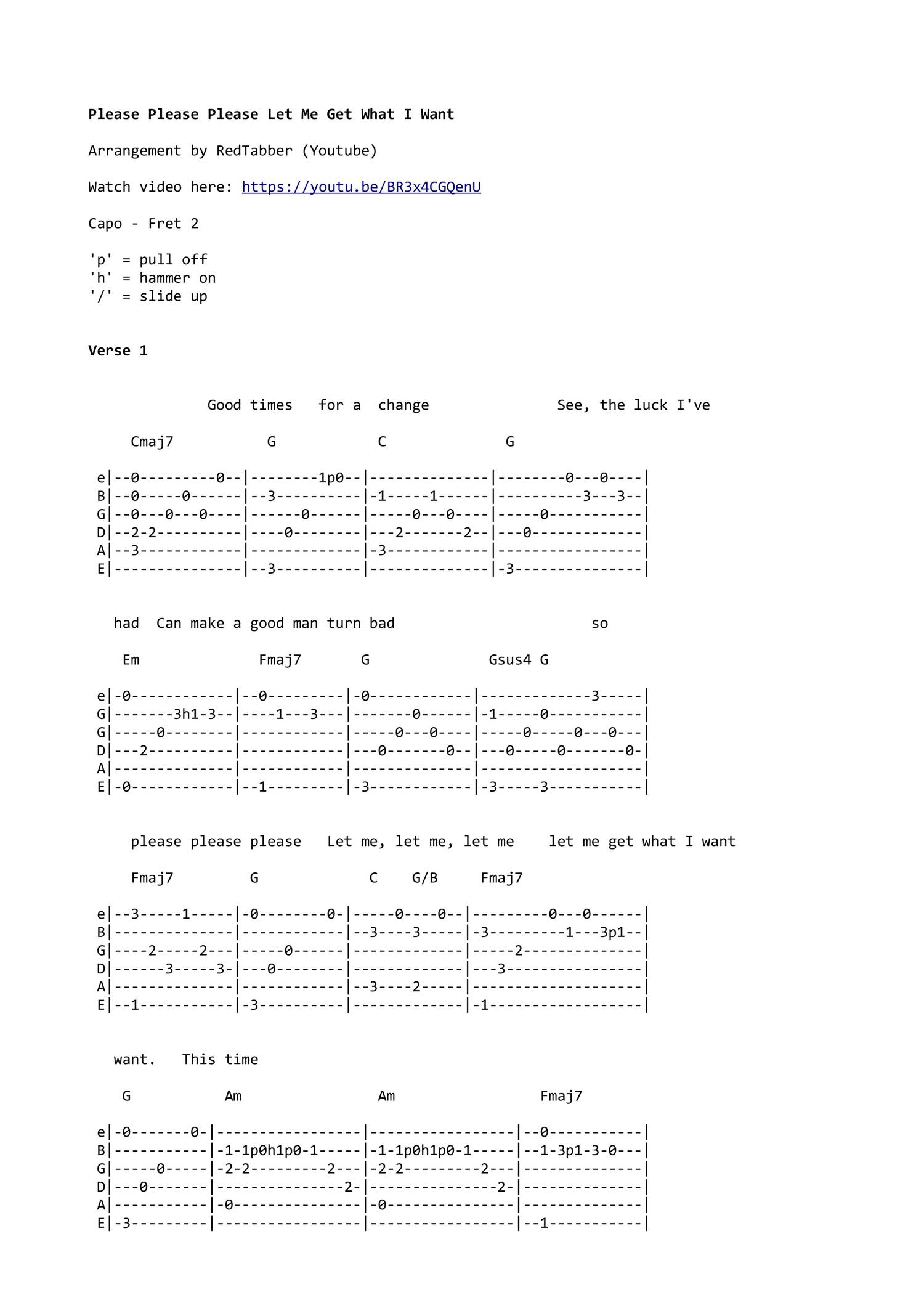

The structure is weirdly simple. There is no traditional verse-chorus-verse layout. It’s just a progression of escalating longing. You’ve got the acoustic guitar, the subtle mandolin at the end, and a melody that feels like it’s constantly descending. It mirrors the feeling of a heavy heart.

- The Mandolin Outro: Johnny Marr played this himself, layering the tracks to give it a folk-waltz vibe. It’s the only part of the song that feels "pretty," which makes the preceding desperation hit even harder.

- The Vocal Delivery: Unlike "This Charming Man" or "Bigmouth Strikes Again," there is no vocal gymnastics here. It’s flat, honest, and vulnerable.

- The Length: At 1:50, it ends before you’re ready. That’s the point. It leaves you wanting more, which is exactly what the lyrics are about.

Honestly, if it were four minutes long, it would be annoying. It would feel like whining. At under two minutes? It’s a prayer.

Why "Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want" is the Ultimate Cinematic Short-Hand

If you are a filmmaker and you want the audience to know your protagonist is a lonely, sensitive soul who feels misunderstood by the world, you play this song. It’s become a trope, but it’s a trope because it works perfectly every single time.

John Hughes was one of the first to really "get" it. He used the Dream Academy’s instrumental cover in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. You remember the scene. It’s the Art Institute of Chicago. Cameron is staring at George Seurat's "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte." As the camera zooms in on the tiny dots of paint—the pointillism—the song swells. It isn't about Ferris; it’s about Cameron’s existential dread. It’s about the fear that if you look too closely at life, it just disappears into nothingness.

Then you have 500 Days of Summer. The song is the literal glue of the relationship. It’s how Tom and Summer meet in the elevator. She hears it bleeding through his headphones and says, "I love The Smiths." It’s a signal. In the "indie" world of the early 2010s, liking this song was a personality trait. It suggested you had "depth."

But the song has been covered by everyone. The Deftones did a version that is surprisingly heavy and haunting. Muse covered it. She & Him (Zooey Deschanel) did a version. Each cover tries to capture that same "Lord, help me" energy, but there’s something about the original 1984 recording that remains untouchable. It’s the specific thinness of the production. It sounds like it was recorded in a drafty room in Manchester, which, effectively, it was.

The Lyrics: A Study in "Good Times" vs. "The Life I've Had"

"Good times for a change."

That opening line is one of the most relatable sentences in the history of the English language. It implies a long, exhausting history of "bad times" without having to list them. Morrissey doesn’t need to tell you what went wrong. You already know because you’ve lived it.

🔗 Read more: Why the Red and Gold Spider-Man Suit Still Splits the Fanbase

The core of Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want is the line: "See, the luck I've had can make a good man turn bad." This is a profound observation on how constant disappointment erodes character. It’s not just about being sad; it’s about the bitterness that sets in when you feel like the universe has a personal vendetta against you.

It’s a very "working-class North of England" sentiment. It’s the feeling of being overlooked.

Wait. Let's talk about the title for a second. It has three "pleases." Not one, not two. Three. It’s a tantrum disguised as a ballad. It’s the linguistic equivalent of someone pulling at your sleeve until you finally look at them. And yet, the song is so polite. "Lord knows it would be the first time." It’s an appeal to a higher power, even if you don’t believe in one.

Misinterpretations and the "Mope Rock" Stigma

For years, critics used this song as a weapon against The Smiths. They called it "self-indulgent." They said it encouraged teenagers to wallow in their own misery.

But that misses the irony.

Morrissey was always a bit of a dramatist. He knew he was being "extra." There is a slight wink in the performance—a recognition that wanting things we can't have is the human condition. It’s not just about a girl or a boy or a job. It’s about the gap between our expectations and our reality.

In a 1984 interview with NME, the band talked about how they wanted to move away from the synth-heavy sound of the 80s. They wanted something "human." You can hear that in the mistakes. The fingers sliding across the strings. The slight hiss in the background. It’s the opposite of a polished pop song. It’s a sketch.

Why We Are Still Listening in 2026

You’d think a song from forty years ago would lose its edge. Especially in an era of hyper-fast TikTok sounds and AI-generated beats. But Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want has actually gained more traction.

Why? Because our "wanting" has only increased. We live in a world of infinite scrolling where we are constantly shown what we don't have. We see the vacations, the bodies, the careers, and the relationships we want, and we can’t have them. The song has become the unofficial anthem of FOMO, though it’s much deeper than that.

It’s also incredibly short, which fits the modern attention span perfectly. But unlike a 15-second clip, it carries an entire emotional arc.

Key Lessons from the Song’s Longevity:

- Vulnerability wins: Being cool is fine, but being honest stays with people longer.

- Brevity is power: You don’t need six minutes to make a point. If you can say it in two, do it.

- The "Vibe" is everything: The mandolin ending does more work than a hundred guitar solos. It sets a mood of quiet contemplation that lingers.

How to Lean into the "Smiths" Mindset (Productively)

If you find yourself relating to this song a little too much lately, it’s easy to spiral. But there’s a way to use that feeling of "longing" to actually get what you want, rather than just singing about it.

- Identify the "Want": In the song, the desire is vague. In real life, specificity is your friend. What is the "it" you want to get? Write it down.

- Check the "Bad Luck" Narrative: Morrissey sings about how his luck makes him turn bad. It’s a great lyric, but a terrible life philosophy. If you start believing you are "unlucky," you stop looking for opportunities.

- Use the "Two-Minute" Rule: If you’re feeling overwhelmed by what you lack, give yourself two minutes (the length of the song) to feel sorry for yourself. Set a timer. Wallow. Then, when the mandolin fades out, move on to a concrete action.

The song is a place to visit, not a place to live. It’s a beautiful, shimmering portrait of a universal feeling, but the "good times" Morrissey asks for usually require us to stop asking and start moving.

Next Steps for the Obsessed:

If you want to dive deeper into why this specific sound works, look into the "Jangle Pop" movement of the early 80s. Specifically, listen to the "Hatful of Hollow" session version of the song—it’s even rawer than the "Louder Than Bombs" version. Also, check out the 2011 remaster of The Queen is Dead (even though this song isn't on it, the production style is the natural evolution of this track). Pay attention to how Marr layers those acoustic tracks; it’s a masterclass for any aspiring bedroom producer.

Now, go put on some headphones, find a rainy window, and let yourself feel it for exactly one minute and fifty seconds. Then, go get what you want.