The coffeehouses were smoky. Greenwich Village was basically a maze of damp basements and poets who hadn't showered in three days, and yet, out of that specific, localized mess, we got a sound that changed everything. People tend to think of sixties female folk singers as just a group of women in long skirts with acoustic guitars, humming about flowers. Honestly? That is a total myth. These women were fierce, often technically superior to their male peers, and they were navigating a music industry that didn't really know what to do with a woman who had her own opinions and a Martins D-28 guitar.

It wasn't just about the "protest song" trope.

Sure, Joan Baez stood on the front lines, but the movement was sprawling. It included the high-lonesome sound of the Appalachians, the sophisticated jazz-inflected melodies of the Canadian prairie, and the gritty, blues-soaked belts of the California coast. If you think it started and ended with "Diamonds and Rust," you're missing about 90% of the picture.

The Technical Brilliance Nobody Mentions

Everyone talks about Bob Dylan’s lyrics. They talk about Phil Ochs’ politics. But when we look at sixties female folk singers, we need to talk about the actual musicianship, which was—frankly—insane.

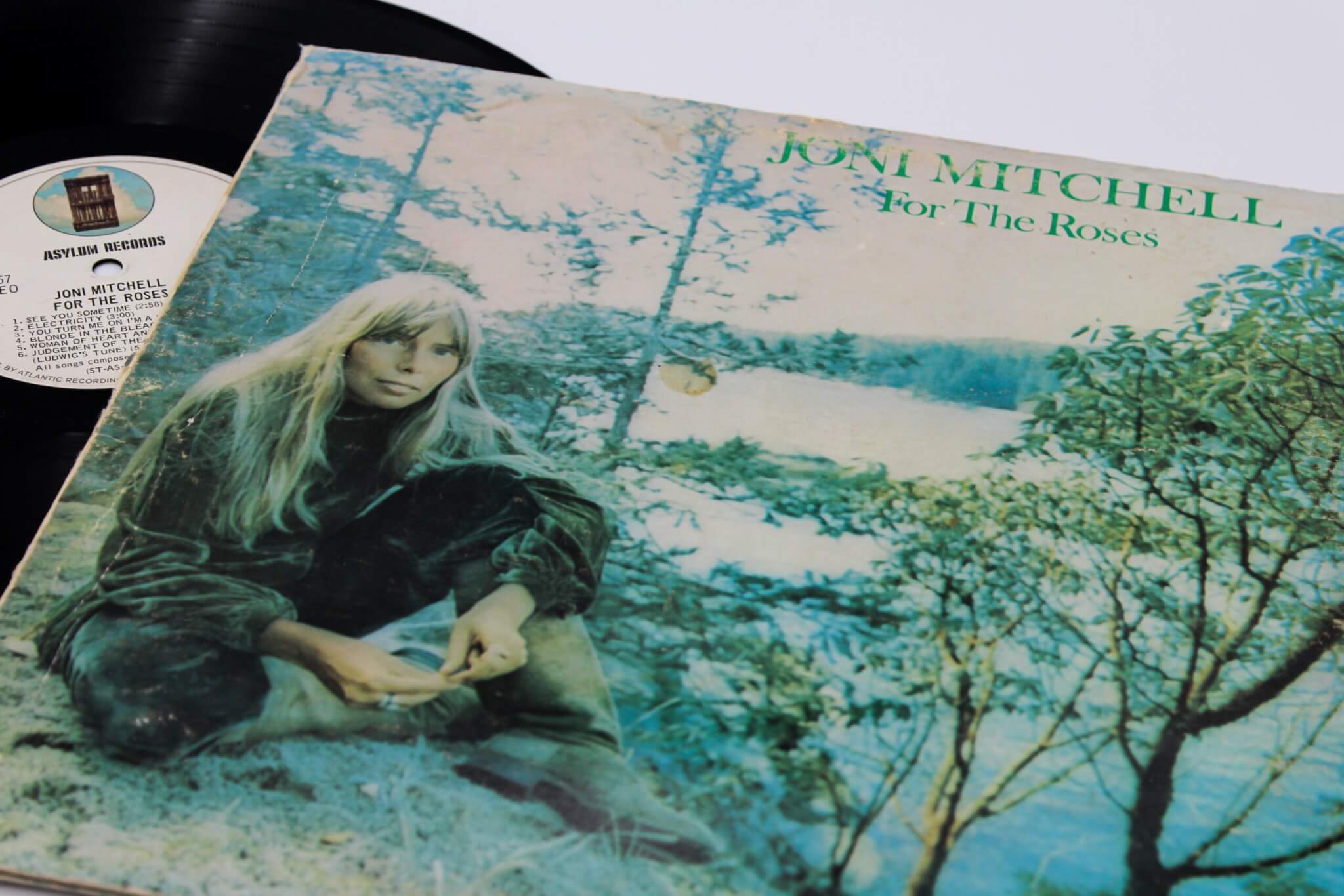

Take Joni Mitchell. Before she became the jazz-fusion icon of the late 70s, she was a folkie in the mid-60s. But she wasn't playing standard chords. Because of a childhood bout with polio, her left hand wasn't as strong as she wanted it to be. Her solution? She invented dozens of open tunings. She was literally rewriting the geometry of the guitar so she could play the complex internal voicings she heard in her head. When you listen to a track like "Cactus Tree," you aren't just hearing a folk song; you're hearing a technical innovation that most male session players of the time couldn't even replicate without a cheat sheet.

Then there’s Odetta.

Lorne Michaels once called her the "spirit of the folk movement." She didn't just sing; she used her guitar, which she nicknamed "Baby," as a percussive instrument. Her voice was an operatic contra-alto that could rattle the windows of a Carnegie Hall. She proved folk wasn't just delicate. It was heavy. It was muscular.

The Greenwich Village Hierarchy

If you were in New York in 1961, the Gerde's Folk City stage was the center of the universe. But it was a bit of a boys' club.

Women like Carolyn Hester were huge stars at the time—Hester actually gave Dylan his first big break by having him play harmonica on her third album—but history has a weird way of centering the men in the room. Hester was a powerhouse. She had this crystalline soprano that felt like it was slicing through the air. Yet, in many retrospective documentaries, she’s relegated to a footnote. That’s a mistake. Without the commercial success of women like Hester and Mary Travers (of Peter, Paul and Mary), the "folk boom" would have likely stayed a niche hobby for academic ethnomusicologists rather than becoming a billboard-topping phenomenon.

✨ Don't miss: Billie Eilish San Jose Concert: Why the SAP Center Shows Were Different

Why the "Pure" Folk Label is a Trap

We love to categorize things. We want sixties female folk singers to stay in a neat little box of "pure" acoustic music. But the artists themselves hated that.

Judy Collins is a perfect example. She started with the traditional ballads—the stuff about "Black Jack Davey" and "The Maid of Constant Sorrow." But she got bored. She was one of the first to recognize the genius of Leonard Cohen, recording "Suzanne" before he even had a career as a singer. She brought in theater music, art songs, and lush orchestrations.

She wasn't a "purist."

Neither was Buffy Sainte-Marie. If you haven't listened to It's My Way! from 1964, go do it right now. She was an Indigenous woman from the Piapot Cree Nation, and she was singing about things that made the establishment incredibly uncomfortable. Her song "Universal Soldier" became the definitive anti-war anthem, but she also experimented with electronic music and the Buchla synthesizer long before most rock bands even knew what a synth was. She was a pioneer of "folk-electronic" before the term existed.

The British Invasion (The Folk Version)

While the US had the Village, the UK had its own scene that was arguably weirder and more influential on modern indie rock.

- Sandy Denny: She joined Fairport Convention and basically invented British Folk-Rock. Her voice had this earthy, tragic weight to it. She’s still the only guest vocalist to ever appear on a Led Zeppelin studio track ("The Battle of Evermore").

- Vashti Bunyan: Her 1970 album Just Another Diamond Day sold almost zero copies when it came out. She was so discouraged she left the music industry for thirty years. Now? She’s a godmother to the "freak folk" movement of the 2000s. Devendra Banhart and Joanna Newsom wouldn't sound the way they do without her.

- Shirley Collins: She didn't want to sound American. She wanted to find the old, bloody, terrifying songs of the English countryside. She helped preserve a musical DNA that was almost lost to the radio.

The Myth of the "Tragic Folk Girl"

There is this annoying tendency in music journalism to frame sixties female folk singers through the lens of tragedy or their relationships with famous men.

Stop doing that.

Karen Dalton is often painted as this tragic, "broken" figure because she struggled with addiction and never found mainstream success. But if you listen to In My Own Time, you aren't hearing a victim. You're hearing a master of phrasing. She sang like Billie Holiday but played a long-neck banjo. She was a "musician's musician." Bob Dylan said she was his favorite singer in the Village. Her lack of fame wasn't a failure of her talent; it was a failure of the industry to market someone who refused to play the "pretty girl" part.

Then you have Janis Ian.

She wrote "Society's Child" when she was just a teenager. It was a song about interracial romance, and it was so controversial that radio stations were burned for playing it. She faced death threats. She was blacklisted. She wasn't some delicate waif; she was a kid standing up to a terrified, racist adult world with nothing but a melody.

How to Actually Listen to This Era

If you want to understand the impact of sixties female folk singers, you have to look past the "Greatest Hits" compilations. You have to look at the b-sides and the live recordings from Newport.

The influence is everywhere today. When you hear Taylor Swift’s Folklore or Evermore, you’re hearing the narrative storytelling techniques perfected by Joni Mitchell. When you hear the raw, guttural honesty of Adrienne Lenker (Big Thief), you’re hearing the ghost of Karen Dalton. Even the "stomp and holler" bands of the 2010s owe everything to the arrangements created by women like Jean Ritchie, who brought the dulcimer to the masses.

It wasn't a fad. It was a fundamental shift in who was allowed to tell the American story.

✨ Don't miss: Blade Runner 2099 on Amazon Prime Video: What’s Actually Happening with the Sequel

Before this era, women in pop were often relegated to singing what they were told by male producers in the Brill Building. The folk movement changed that. It gave women the agency to write their own lyrics, tune their own guitars, and—for better or worse—live their lives on their own terms.

Actionable Ways to Explore the Genre Further

Don't just stick to the Spotify "Top 5." To really get the depth of this movement, you need to dig a little deeper into the archives.

- Listen to "The Silkie": Seek out the 1965 recordings of this English group, specifically their cover of "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away." It's a masterclass in folk harmony.

- Watch 'Festival!' (1967): This documentary by Murray Lerner captures the Newport Folk Festival at its peak. You’ll see the raw energy of these performances before they were polished by studio magic.

- Compare Interpretations: Take a traditional song like "Silver Dagger." Listen to Joan Baez’s 1960 version, then find Dolly Parton’s later take. Seeing how these women inhabit the same "ghost" stories shows you the versatility of the folk form.

- Read 'Girls Like Us': Sheila Weller’s book explores the lives of Carole King, Joni Mitchell, and Carly Simon. It gives the necessary social context for why their transition from "folk" to "singer-songwriter" was such a massive cultural shift.

- Track the Tunings: If you're a guitar player, look up the "Joni Mitchell Tuning Database." Trying to play these songs in standard EADGBE is a losing battle and will give you a new respect for the technical complexity of the era.

The legacy of these artists isn't found in a museum or a "Classic Rock" Hall of Fame. It's found in the fact that today, a woman can pick up an acoustic guitar, talk about her trauma, her politics, or her weirdest dreams, and expect to be heard. That door didn't just open itself; the women of the sixties kicked it down.