Twenty-four notes. That is it. No lyrics, no complex orchestration, just a simple G-major arpeggio played on a beat-up piece of brass. Yet, when you hear those first few slow, mournful tones of taps on the bugle, everything stops. People stand straighter. They remove their hats. Honestly, even if you aren't particularly patriotic, there is something about that specific frequency that just hits you right in the chest.

It is arguably the most famous piece of music in American history. It is also one of the most misunderstood. Most folks assume it’s been around since the dawn of the Republic, or maybe that it was written by some famous composer in a fancy studio. The reality is way more gritty. It was born in the mud and blood of the Civil War, specifically during the Peninsular Campaign of 1862. It wasn't a grand artistic statement. It was a practical solution to a very grim problem.

The Harrison’s Landing Myth vs. Reality

If you spend enough time on the internet, you’ll eventually run into a viral story about a Union captain finding a dead Confederate soldier who turned out to be his son. The story goes that he found a scrap of music in the boy's pocket and played it at the funeral. It's a real tear-jerker. It is also completely fake. Total fiction.

The real story involves General Daniel Butterfield and his bugler, Oliver Willcox Norton. They were stationed at Harrison’s Landing in Virginia. Butterfield was apparently annoyed by the standard "Extinguish Lights" call, which he thought sounded too formal and not nearly peaceful enough for the end of a long day of fighting. He summoned Norton to his tent one July night. Butterfield couldn't read a lick of music, but he had some notes in his head. He scribbled them on the back of an envelope. Norton played them. Butterfield tweaked them—shortening some, lengthening others—until they landed on the haunting melody we know today.

Norton eventually wrote about this in his memoirs. He described how the call spread like wildfire. Other units heard it across the camps and asked their own buglers to learn it. It was organic. Within months, it was being played across the entire Army of the Potomac. It became the unofficial "lights out" signal because it felt right. It sounded like sleep.

Why These 24 Notes Work (The Science of the Sound)

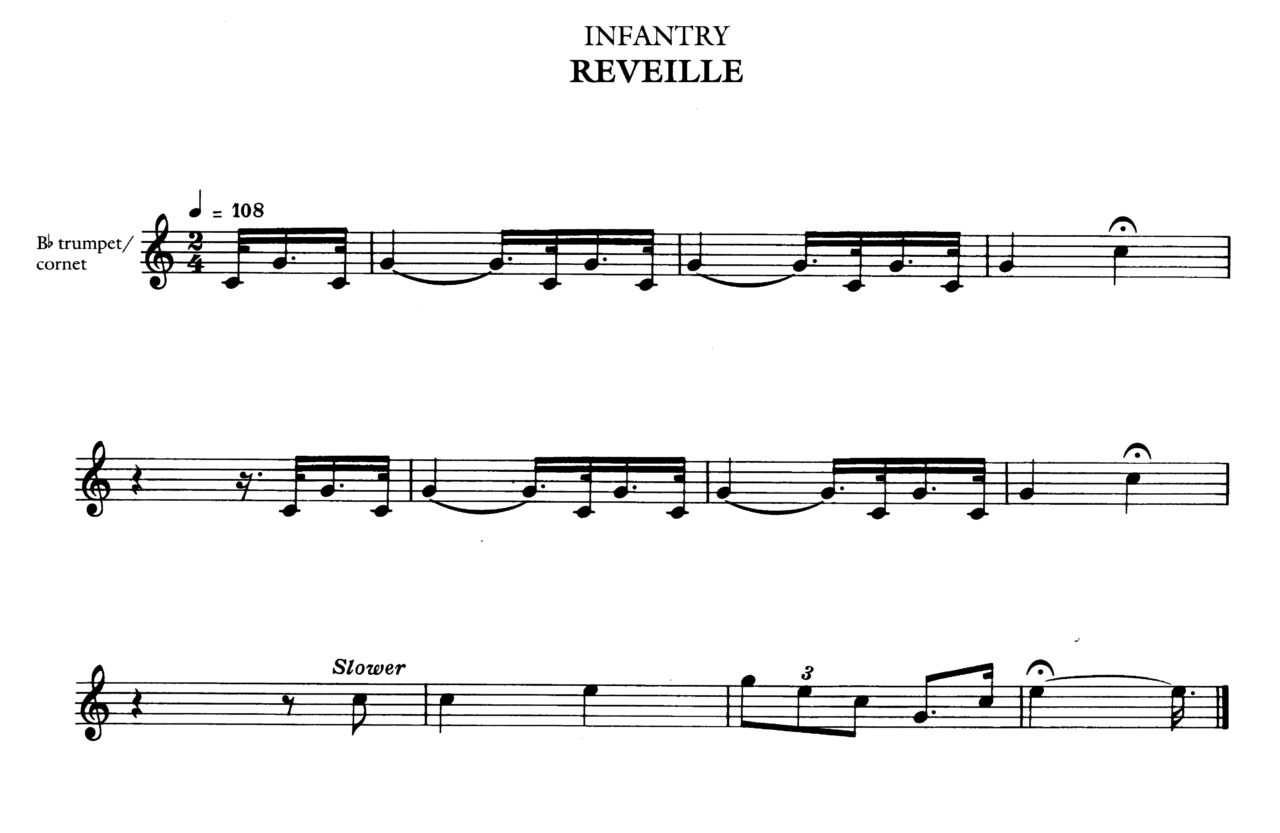

Ever wonder why it sounds so "open"? Bugles don't have valves. You can't play a full scale on them. You are limited to what they call "natural harmonics."

When someone performs taps on the bugle, they are playing within a very specific harmonic series. The notes are exclusively G, C, and E. Because there are no sharps or flats, the melody feels incredibly stable and grounded. There is no tension seeking resolution, which is why it feels so final. It’s the musical equivalent of a deep exhale.

Musicians will tell you that the "swing" or the rhythm of the piece is what makes a live performance so different from a recording. There’s a slight lilt to it. If you play it perfectly straight, like a robot, it loses the soul. It needs to breathe. It needs that human imperfection—the slight vibrato on the final high G that hangs in the air just a second longer than you expect.

From Bedtime to Burial

It’s weird to think that a song meant to tell soldiers to go to sleep became the standard for funerals. The transition happened during that same Peninsular Campaign. A soldier in Captain John Tidball’s battery died, and the unit wanted to give him a proper burial with military honors.

The problem? They were way too close to enemy lines.

If they had fired the traditional three-volley salute over the grave, the Confederates would have thought an attack was starting and opened fire with their cannons. It was a powder keg. Tidball had to get creative. He decided that instead of firing rifles, he’d have a bugler play Butterfield’s new "lights out" call. It was a stroke of genius. It honored the dead without starting a battle.

By 1891, the U.S. Army officially made it a requirement for military funerals. It became the bridge between the world of the living and the world of the dead. It tells the soldier their "long day" is finally over.

The "Echo Taps" Controversy

If you’ve been to a large ceremony at Arlington or a high-profile memorial, you might have heard two buglers playing at once. One stands near the grave, and another stands far off in the distance—sometimes hundreds of yards away—playing the same notes a few beats behind. This is called "Echo Taps."

Here is a bit of insider knowledge: Most traditionalists and many veteran organizations actually hate this.

The Air Force, for instance, has officially discouraged Echo Taps for years. Why? Because the original intent of the call is singular and lonely. It’s meant to be one person, one horn, one message. When you add an echo, it can get messy. It risks sounding like a performance rather than a prayer. Plus, it’s notoriously hard to pull off. If the second bugler is even slightly out of tune or out of sync, it sounds chaotic.

Still, for many families, that haunting response from the trees is the most emotional part of the service. It’s a debate that usually ends in a stalemate, but if you want to stay strictly by the book (specifically Army Field Manual 3-21.5), you stick to a single bugler.

How to Tell if a Bugler is Actually Playing

This is a bit of a "don't look behind the curtain" moment. Because there are fewer and fewer trained buglers in the military today, many honor guards use a "digital bugle."

It looks like a real instrument. The person holds it to their lips. They even move their fingers if they’re committed to the bit. But inside the bell is a small, high-powered speaker. You press a button, and a perfect recording of a professional bugler from the U.S. Marine Band or the Army Band plays.

How can you tell the difference? Look at the "bugler's" throat. If they aren't taking big, deep breaths or if their neck muscles aren't straining, it’s a digital insert. Also, if the sound is absolutely flawless despite it being 10 degrees outside with a 30 mph wind, it's likely a recording. Real brass is temperamental. Cold weather makes the pitch go sharp. Humidity makes it flat. A live performance has "weather" in it.

📖 Related: Why Art of War Book Quotes Still Rule the Boardroom and the Battlefield

The Proper Etiquette (What You Actually Do)

When you hear taps on the bugle at a ceremony, don't just stand there looking at your phone. There is a very specific protocol.

- If you are in uniform: You salute from the first note until the last note is finished.

- If you are a civilian: You stand at attention. Take off your hat. Place your right hand over your heart.

- If you are a veteran not in uniform: You have a choice. Under the National Defense Authorization Act of 2008, veterans and active-duty members not in uniform are legally allowed to render a military-style hand salute during the playing of Taps. Most old-school guys still do this, and it’s a powerful thing to see.

- Silence: Do not whisper. Do not shush your kids (just hold them still). Let the silence do the work.

Misconceptions About the Lyrics

There are no official lyrics. None.

However, because humans love to fill gaps, several versions have cropped up over the years. The most common one starts with "Day is done, gone the sun..."

You’ll hear kids at scout camps sing these lyrics every night. It’s fine for campfires. But at a military funeral? You will never hear lyrics sung. The music is intended to be the final word. Adding lyrics to it is kind of like putting a hat on a statue—it just clutters up the dignity of the original form.

Actionable Steps for Honoring the Tradition

If you are involved in planning a memorial or simply want to appreciate the history more deeply, here is what actually matters:

- Request a Live Bugler: If you are planning a funeral for a veteran, try to get a live human through the "Bugles Across America" organization. They are volunteers who show up to ensure a recording isn't used. The "live" sound carries a different weight.

- Support the National Taps Archive: Groups like Taps for Veterans work to preserve the history of the call. They have digitised records of Norton’s original bugle and Butterfield’s notes.

- Listen to the Variations: Go on YouTube and find a recording from the 1940s compared to one from today. You can hear how the "tempo" has slowed down over the decades. It used to be much faster—more of a "hurry up and sleep" vibe. Now, it's a slow, dragging "goodbye."

- Check the Instrument: If you find an old bugle in an antique shop, look for a "G" stamp. True military bugles are pitched in the key of G. If it’s in B-flat, it’s likely a repurposed trumpet or a ceremonial piece not intended for field use.

The power of this melody isn't in its complexity. It’s in its honesty. It acknowledges that the day is over, the work is finished, and it is time to rest. Whether that rest is for the night or for eternity, those 24 notes are the only thing that seems to say it correctly.

Next time you hear it, don't just listen to the melody. Listen to the silence between the notes. That is where the real history lives. Be mindful of the breath the bugler takes before the final high note—it’s the same breath thousands of soldiers have taken for over a century, trying to get it just right for the person who isn't there to hear it.