It was the year the alphabet ran out. If you lived through it, you probably remember the feeling of absolute exhaustion by October. Most years, we get a dozen or so named storms and call it a day. But 2005 was different. The 2005 Atlantic hurricane season didn't just break records; it smashed them into tiny, unrecognizable pieces. It was a relentless, high-speed assembly line of tropical cyclones that fundamentally changed how we think about emergency management, climate shifts, and the sheer power of the ocean.

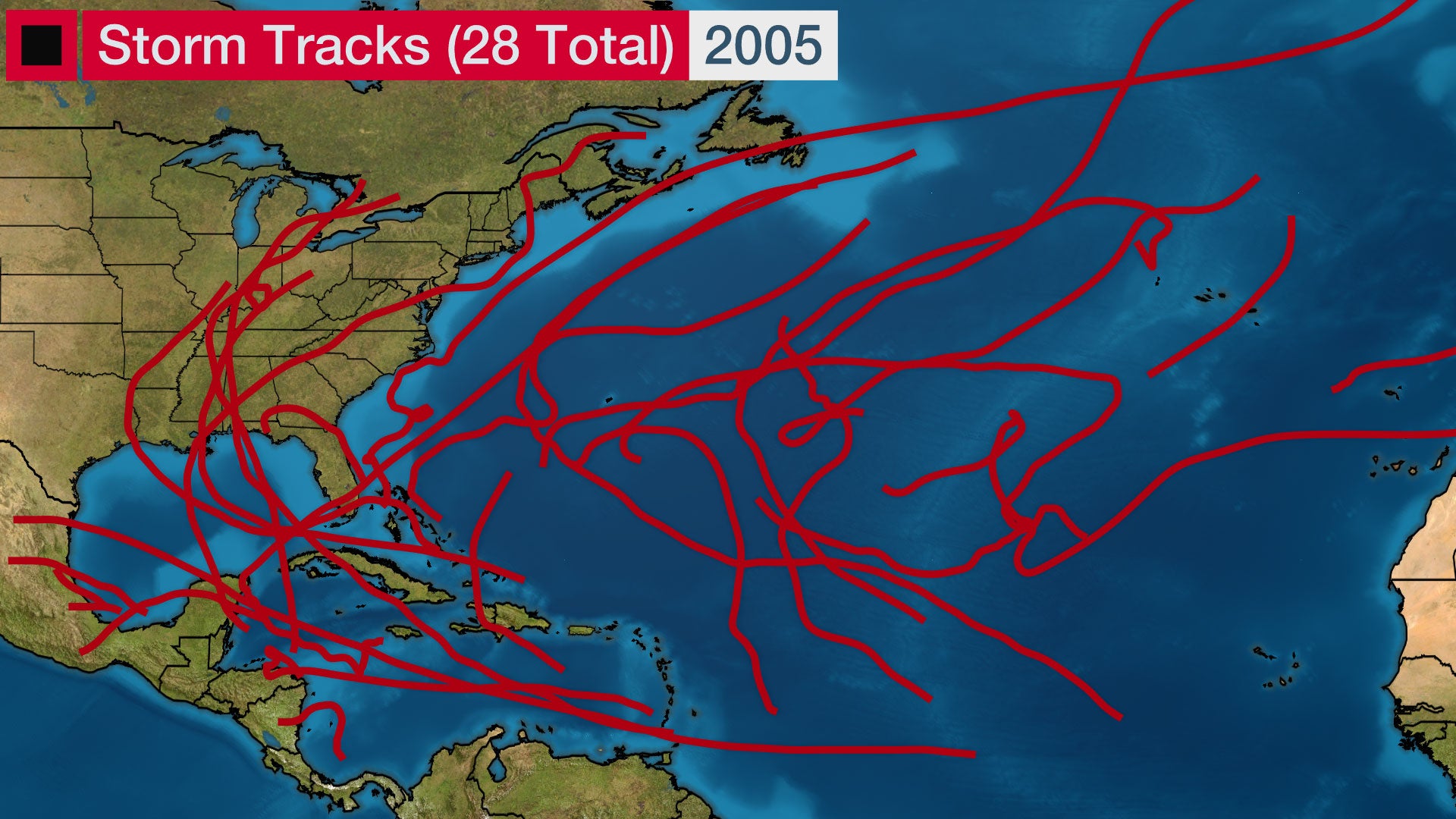

Honestly, looking back at the data now, it feels like a fever dream. We saw 28 named storms. That's insane. The National Hurricane Center had to pivot to the Greek alphabet for the first time in history because they literally ran out of names from the pre-determined list. From the catastrophic surge of Katrina to the record-breaking intensity of Wilma, the season was a masterclass in worst-case scenarios. It wasn't just about the numbers, though. It was about the human cost and the realization that our infrastructure was—and in many ways, still is—woefully unprepared for a "hyperactive" year.

The Chaos of a Record-Breaking Calendar

The season started early. Usually, things don't get spicy until August. Not in 2005. Arlene kicked things off on June 8, and by July, we already had two major hurricanes, Dennis and Emily. Dennis slammed into the Florida Panhandle as a Category 3, which is a hell of a way to start the summer. Most people were still buying sunscreen while FEMA was already mobilizing.

Think about the sheer density of events. Between June and January—yes, the season actually dragged into January 2006—there was barely a moment to breathe. We saw 15 hurricanes. Seven of those were "major" (Category 3 or higher). To put that in perspective, a "normal" year usually sees about seven hurricanes total.

The pressure on forecasters at the NHC in Miami was immense. Dr. Max Mayfield, who was the director at the time, became a household face because he was on TV constantly, looking increasingly tired as storm after storm lined up in the Main Development Region. It wasn't just the frequency; it was the rapid intensification. We saw storms jump from "tropical storm" to "major hurricane" in a matter of hours. That's a nightmare for evacuations. If a storm intensifies overnight while people are sleeping, you've got a recipe for disaster.

Katrina, Rita, and the Gulf Coast Nightmare

We have to talk about the "Big Three." Katrina, Rita, and Wilma.

Katrina is the one everyone remembers, and for good reason. It wasn't even the strongest storm of the year in terms of wind speed—that honor goes to Wilma—but it was the most destructive. When Katrina hit the Gulf Coast on August 29, it brought a storm surge that New Orleans' levees simply couldn't handle. People talk about "the storm," but the tragedy was really a failure of engineering and policy.

- The Levee Breach: Over 50 breaches in the surge protection system around New Orleans.

- The Scope: 90,000 square miles were affected. That's the size of the United Kingdom.

- The Cost: Roughly $125 billion in damages, a record that stood for over a decade.

Then came Rita in September. If Katrina was the gut punch, Rita was the follow-up. It reached Category 5 status in the Gulf of Mexico with a central pressure of 895 mbar. It forced one of the largest evacuations in U.S. history. If you were in Houston at the time, you remember the gridlock. People were stuck on I-45 for 20 hours in sweltering heat. It was a mess. Rita eventually weakened before landfall, but it still walloped the Texas-Louisiana border.

👉 See also: Mia James Amber Alert: Why This Texas Case Stayed On Everyone's Mind

The Wilma Factor

Then there's Wilma. October 2005. This storm was a monster. In just 24 hours, it went from a 70-mph tropical storm to a 175-mph Category 5 behemoth. It still holds the record for the lowest central pressure ever recorded in the Atlantic basin: 882 mbar. Lower pressure basically means a more intense, tighter, and more violent storm.

Wilma eventually hit Cozumel and then crossed Florida. I remember people in South Florida thinking they were "used" to hurricanes after 2004, but Wilma caught them off guard. It stayed over the Yucatan for two days, just grinding everything into sand, before accelerating toward Florida. It was a reminder that the tail end of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season was just as dangerous as the peak.

Why Did This Happen?

Scientists have spent two decades arguing about why 2005 was so active. Was it a fluke? Climate change? The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO)?

Basically, it was a "perfect storm" of conditions. The sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic were record-breakingly warm. Warm water is the fuel for hurricanes. If the water is hot, the storm has more energy to draw from. Combine that with very low wind shear—which is the change in wind speed and direction at different altitudes. High wind shear rips storms apart before they can organize. In 2005, the shear was almost non-existent for long stretches, allowing storms to build into perfect, terrifying spirals.

There’s also the "Loop Current" in the Gulf of Mexico. This is a current of exceptionally warm, deep water. Both Katrina and Rita passed right over it. When a hurricane hits that deep reservoir of heat, it’s like throwing gasoline on a fire. They don't just grow; they explode.

📖 Related: Did No Taxes On Tips and Overtime Pass? What You Actually Need to Know Right Now

Lessons We (Hopefully) Learned

The aftermath of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season changed everything. Before 2005, FEMA was seen as a reasonably competent agency. After Katrina, it became a symbol of bureaucratic failure. This led to the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006, which gave FEMA more autonomy and better funding.

We also learned that our communication was broken. The "cone of uncertainty" is great for meteorologists, but the average person often thinks if they are outside the line, they are safe. 2005 proved that the impacts—flooding, tornadoes, surge—happen far outside that little white cone.

- Water, not wind, is the killer. Most deaths in 2005 weren't from roofs blowing off; they were from drowning. Storm surge and inland flooding are the real enemies.

- Redundancy is king. You can't rely on cell towers. In 2005, communication in New Orleans went dark. Today, we have better satellite integration, but the lesson remains: have a backup for your backup.

- The "End" of the Season is a Suggestion. Hurricane Epsilon formed in late November and lasted into December. Tropical Storm Zeta formed on December 30. Never let your guard down just because the calendar says it's November.

Moving Forward: Your Action Plan

If 2005 taught us anything, it’s that "unprecedented" is a word we use far too often. These seasons will happen again. Whether it's the 2024 season or a decade from now, the patterns are clear.

Audit your flood insurance today. Seriously. Most homeowners' insurance doesn't cover rising water. People in 2005 found this out the hard way when they lost everything and received zero from their primary providers. If you live within 50 miles of a coast, or even near a major river, get a separate flood policy.

Digitalize your "Go-Bag" documents. In 2005, people fled with paper birth certificates and deeds that got soaked or lost. Scan everything to a secure cloud drive and an encrypted USB stick. Having your insurance policy number and a photo of your ID on your phone can save you weeks of headaches during the recovery phase.

Understand your local topography. Don't just know your evacuation zone; know your elevation. If you're at 5 feet above sea level, you're in trouble during a surge regardless of what the "zone" says. Use tools like the USGS's National Map to see exactly where your house sits. Knowledge is the only thing that beats the panic when a storm like Wilma or Katrina starts spinning up in the Gulf.

✨ Don't miss: Getting Around the Mess: What Happened With the Accident on the 60 Freeway Today

The 2005 season wasn't just a statistical outlier. It was a warning shot. It showed us exactly what the ocean is capable of when the conditions are right—and it’s a reminder that we are always living at the mercy of the atmosphere.