You’ve seen them. The guy in the corner of the gym swinging sixty-pound dumbbells like he’s trying to take flight, his back arching, his neck straining, basically doing a rhythmic dance that has almost nothing to do with muscle growth. It’s painful to watch. The bent over lat raise—or the rear delt fly, if you want to be technical—is one of those movements that everyone thinks they understand but almost nobody actually nails.

It’s tricky. Your rear deltoids are small. Like, surprisingly small. They aren't meant to move massive slabs of iron, yet the ego often takes over the second we pick up a pair of dumbbells.

If you want those "3D shoulders," you can't just spam overhead presses and side raises. You need the back of the shoulder to pop. Without it, you look flat from the side. But honestly, most people just end up training their traps and rhomboids because their form is, well, garbage. Let's fix that.

📖 Related: Dr Ian Smith Shred Diet: Why This Retro Plan Is Making a Huge Comeback

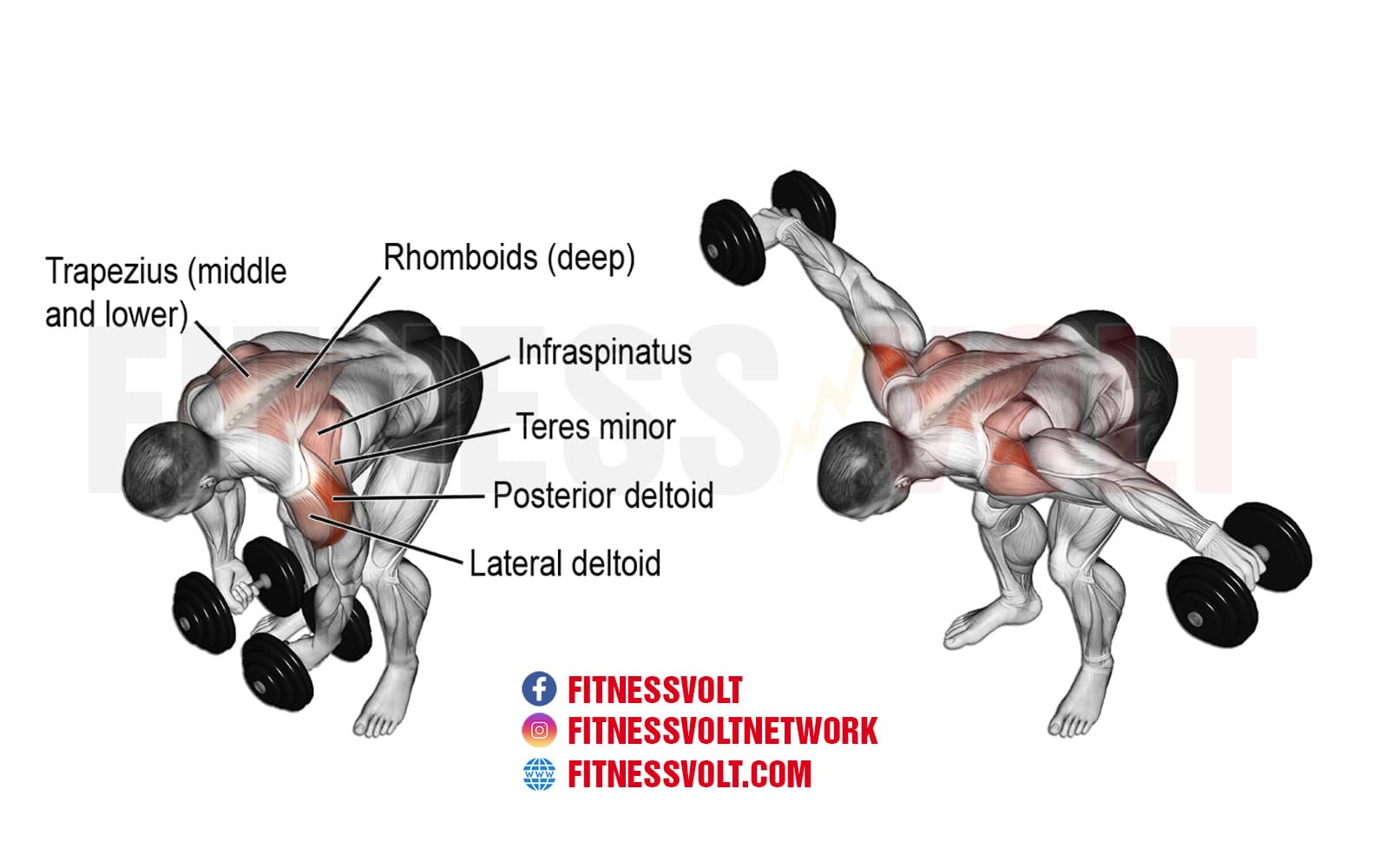

The Anatomy of the Bent Over Lat Raise

The primary target here is the posterior deltoid. This muscle originates on the spine of the scapula and inserts into the humerus. Its job? Horizontal abduction. Basically, moving your arm away from the midline of your body while you're bent over.

But here is the catch. The human body is a master of efficiency. If a movement feels too heavy, your brain will automatically recruit the big players—the trapezius and the latissimus dorsi—to help out. When you swing the weights, you’re using momentum and back strength, leaving the rear delts essentially untouched. Dr. Mike Israetel from Renaissance Periodization often points out that the stimulus-to-fatigue ratio is what matters. If you're exhausted but your rear delts aren't burning, you've failed the lift.

Why Your Grip Matters More Than You Think

Try this right now. Hold your hand out in front of you. Turn your palm down (pronated). Now turn it so your thumb faces up (neutral). Notice the shift in your shoulder?

Most people perform the bent over lat raise with a palms-facing-each-other grip. That’s fine. It’s comfortable. But if you want to truly isolate the rear delt, try a palms-down grip and keep your pinkies high as you raise the weight. This slight internal rotation can often help "find" the muscle that usually stays hidden. It’s a subtle tweak. It feels weird at first. But the contraction is night and day.

Setting Up for Success (Stop Standing Up)

The biggest mistake is the angle of the torso. "Bent over" shouldn't mean a slight 20-degree lean. If you’re too upright, you’re just doing a messy side raise.

You need to be nearly parallel to the floor. Gravity works vertically. If you want the resistance to hit the back of your shoulder, your back needs to be the "table" that the weight moves away from.

- Chest-Supported is King: If you have access to an incline bench, use it. Lay chest-down. This eliminates the "cheat" factor. You can't use your legs or lower back to swing the weight when your chest is glued to a bench.

- The Head Position: Don't look at yourself in the mirror. It’s tempting, I know. But cranking your neck up creates unnecessary tension in the cervical spine. Look at the floor about two feet in front of you. Keep the spine neutral.

- Micro-Bend in the Elbows: You aren't a bird. Don't lock your arms out perfectly straight, as that puts immense pressure on the elbow joint. Keep a soft bend, but don't let that bend change during the rep. If the angle of your elbow is closing and opening, you’re doing a row. We don't want a row.

Common Blunders That Kill Your Gains

We need to talk about the "swing."

The bent over lat raise is a finesse movement. If you’re using the 40lb dumbbells and you’ve been training for less than five years, you’re probably doing it wrong. Professional bodybuilders often stay in the 15-25lb range for this specific exercise. Why? Because the rear delt is a small muscle group that responds better to high volume and metabolic stress than pure, heavy load.

Think about "pushing" the weights out to the walls, rather than "lifting" them up to the ceiling. This mental cue helps keep the traps out of the equation. If you feel your shoulder blades pinching together at the top, you’ve gone too far. The scapula should remain relatively stable while the humerus moves.

The Problem with "Tucking"

People often let the weights drift back toward their hips. This engages the lats. The lats are huge. They will happily take over the entire set if you let them. To avoid this, keep the dumbbells path directly in line with your chest or even slightly forward. It makes the weight feel twice as heavy. That's a good thing.

Scientific Context and Volume

According to a study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, the posterior deltoid shows maximum activation when the torso is horizontal and the arms are moved at a 90-degree angle relative to the torso.

How often should you do them? Since the rear delts are primarily slow-twitch fibers, they recover quickly. You can hit them 2-4 times a week.

- High Reps: 15-25 reps per set.

- Short Rest: 30-60 seconds. Keep the blood in the muscle.

- Slow Eccentric: Don't let the weights drop. Control them on the way down. The lowering phase is where a lot of the muscle damage (the good kind) happens.

Variations That Actually Work

If dumbbells feel clunky, there are other ways to skin the cat.

🔗 Read more: The Doctor Fired for Social Media Post Reality: Why Your Feed is Now a Liability

Cable Rear Delt Flyes: Cables are arguably better than dumbbells because they provide constant tension. With dumbbells, there is no tension at the bottom of the movement. With cables, the muscle is working from the very start to the very finish.

The "Incline" Variant: Set a bench to a 45-degree angle. Sit facing it. This allows for a different range of motion and can be easier on the lower back for people who struggle with a traditional standing bent over lat raise.

Band Pull-Aparts: Not exactly a raise, but a phenomenal primer. Use these as a warm-up to wake up the nerves in your upper back before moving to the heavy stuff.

Practical Next Steps for Your Next Workout

Don't just add this to the end of your workout when you're exhausted. If your rear delts are a weakness, do them first.

👉 See also: What Really Happened With the Shearer's Foods Oyster Cracker Recall

Start your next shoulder or "pull" day with a chest-supported bent over lat raise. Use a weight that feels embarrassingly light. Perform 3 sets of 20 reps. Focus entirely on the "stretch" at the bottom and the "push" to the sides. Avoid the temptation to look in the mirror. Focus on the sensation in the back of your shoulder.

Once you can do all 60 reps with perfect, swing-free form, only then should you consider moving up by 2.5 or 5 pounds. The path to big shoulders isn't paved with heavy weights; it's built with consistent, excruciatingly perfect technique. Stop swinging. Start growing.

Check your ego at the rack and watch your shoulders finally start to fill out.