Money doesn't just stay in the bank. You’ve probably noticed that when you get paid, a chunk of that cash stays in your checking account, but a decent sliver gets pulled out as physical paper. Maybe it’s for a weekend trip to a farmer's market or just to have "emergency cash" in your wallet. Economists call this leakage.

The currency drain ratio formula is how we measure that leakage, and honestly, it’s one of the most underrated metrics in finance.

If you’ve ever looked at how the Federal Reserve or any central bank tries to stimulate an economy, they usually talk about the money multiplier. They think if they inject $1,000, it’ll turn into $10,000. But it doesn't. Not even close. Why? Because of the drain. People like holding onto green paper, and every dollar you tuck under your mattress is a dollar that isn't being lent out by a bank to start a new business or buy a house. It stops the "magic" of fractional reserve banking dead in its tracks.

Understanding the actual currency drain ratio formula

Basically, you’re looking at the relationship between how much cash the public holds versus how much they keep in deposit accounts. The math is actually pretty straightforward, even if the implications are messy.

The currency drain ratio formula is expressed as:

$$C = \frac{k}{D}$$

💡 You might also like: Why Your Civil FE Practice Exam Scores Are Lying to You

In this setup, $C$ represents the currency drain ratio. The $k$ is the amount of currency held by the non-bank public. Finally, $D$ is the total amount of checkable deposits in the banking system.

It’s a ratio. Simple.

If people hold $200 in cash for every $1,000 they have in the bank, the ratio is 0.2. But don't let the simplicity fool you. This little decimal point dictates the entire strength of a nation's monetary policy. When this ratio spikes, the money multiplier collapses. It’s like trying to fill a bathtub when the drain is wide open. You can pump as much water (liquidity) as you want into the tub, but if everyone is hoarding cash, the level never rises.

Why people suddenly hoard cash

It’s about trust.

During the 2008 financial crisis, and again during the weirdness of 2020, we saw shifts in how people treated their bank accounts. If you don't trust the bank to stay solvent, you pull the money out. That’s a "drain." But it isn't always about fear. Sometimes it’s just about convenience or the "shadow economy."

In countries with high taxes or heavy regulations, the currency drain ratio formula usually yields a much higher number. Why? Because people are doing business in cash to stay off the grid. If you’re paying your contractor in $100 bills to avoid a paper trail, that money has "drained" out of the formal banking system. It can't be multiplied. It can't be used by the bank to issue a car loan to your neighbor.

Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz famously dug into this in A Monetary History of the United States. They pointed out that during the Great Depression, the drastic increase in the currency-to-deposit ratio was a primary driver of the money supply's collapse. People didn't just lose money; the money that existed stopped moving.

The Money Multiplier's Worst Enemy

You’ve likely heard the textbook definition of the money multiplier. It’s usually taught as $1/R$, where $R$ is the reserve requirement. If the Fed says banks must keep 10%, then the multiplier is 10.

That is a total fantasy.

🔗 Read more: PNC High Yield Savings: Why You Might Not See the Best Rates in Your Zip Code

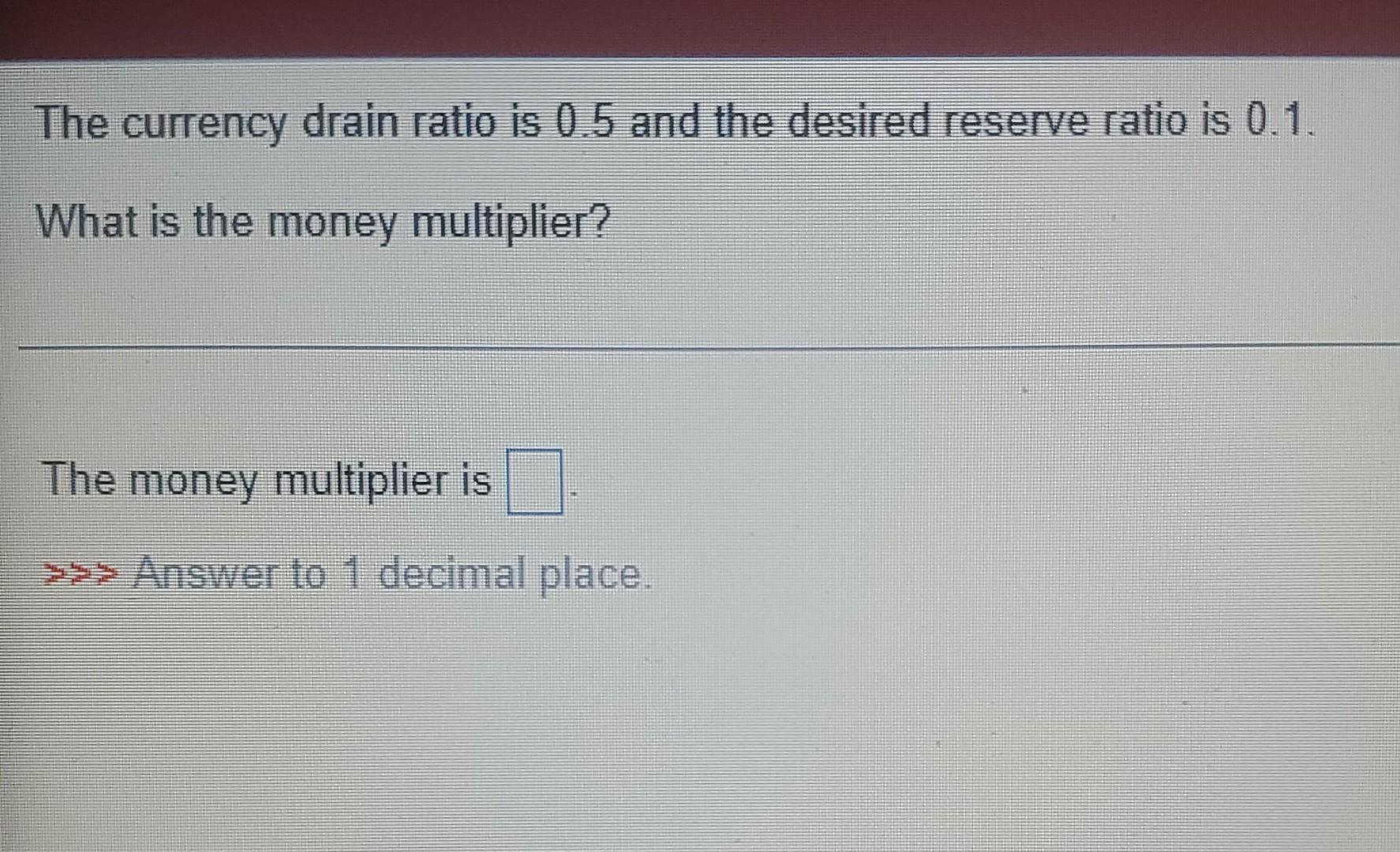

In the real world, the multiplier is significantly lower because we have to account for the drain. The real formula for the money multiplier looks more like this:

$$m = \frac{1 + k}{R + k}$$

See that $k$ in there? That’s our currency drain. If $k$ is zero—meaning nobody ever holds cash—the multiplier is huge. But as $k$ rises, the denominator gets heavier and the numerator doesn't keep up. The whole thing shrinks.

Practical Impact on Your Wallet

Think about it this way. When the central bank lowers interest rates, they want you to spend. They want banks to lend. But if everyone decides that this is the year to keep $5,000 in a safe at home, the bank has $5,000 less to lend out. Multiply that by millions of people.

This is why "liquidity traps" happen. The government pulls every lever they have, but the currency drain ratio formula shows that the public is simply absorbing the cash like a sponge.

The Digital Shift: Is the Drain Dying?

We’re moving toward a cashless society, right? You’d think the currency drain would be hitting zero. Venmo, Apple Pay, and credit cards should, in theory, keep every cent inside the digital banking perimeter.

But it’s not happening.

Interestingly, the amount of physical currency in circulation has actually increased in many developed nations over the last decade. It’s a paradox. We use cash less for buying coffee, but we hold more of it as a store of value. Or, perhaps, for transactions we’d rather not have recorded on a blockchain or a bank statement.

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) are the "fix" the government wants to use to plug this drain. If the "cash" is digital and stays within the central bank's ledger, the drain ratio effectively hits zero. They get total control over the multiplier. That’s a scary thought for privacy advocates, but a dream for macroeconomists who want "perfect" transmission of monetary policy.

Real-World Nuance: It's Not Just a Number

The currency drain ratio formula isn't static. It breathes.

It changes during the holidays. In December, the ratio usually spikes. People withdraw cash for gifts, tips, and travel. The Fed actually has to account for this seasonal drain to prevent the money supply from accidentally tightening during the busiest shopping season of the year.

Then there's the international factor. A huge percentage of U.S. $100 bills aren't even in America. They are held in overseas reserves or by individuals in unstable economies who trust the Dollar more than their local Lira or Pesos. This "international drain" means the U.S. money multiplier is naturally suppressed because our "leakage" isn't just to under-the-mattress—it’s to under-the-mattress in Zurich or Tokyo.

Factors that tweak the ratio:

- Interest Rates: If savings accounts pay 5%, you’re less likely to keep cash in your sock drawer. The drain decreases.

- Banking Infrastructure: In rural areas with fewer ATMs, people hold more cash. Higher drain.

- Tax Policy: High VAT or sales tax often drives cash-only "off the books" behavior.

- Economic Stability: When things get shaky, people want the "tangibility" of paper.

Actionable Insights for the Savvy Observer

If you’re trying to track where the economy is going, don't just look at the stock market. Look at the velocity of money and the drain.

- Monitor the Fed's H.4.1 Release: This shows "Currency in Circulation." If you see this number spiking while bank deposits are stagnant, you know the currency drain ratio is climbing. This is often a precursor to a credit crunch.

- Evaluate "Cashless" Trends: Watch for the adoption of CBDCs. If a government successfully launches a digital version of their currency, the currency drain ratio formula becomes obsolete, and the central bank gains unprecedented power over inflation and lending.

- Hedge Against Drain Volatility: In periods of high currency drain, banks struggle with liquidity. This is when they raise "teaser" rates on CDs to lure the cash back into the system. If you see the drain rising, look for banks getting desperate for your deposits—they’ll pay a premium for them.

Understanding this ratio tells you what the "average" person thinks about the future. When people feel safe, they trust the digital ledger. When they feel the ground shifting, they reach for the paper. The math doesn't lie; it just reflects our collective anxiety or confidence.

Next time you hear about a "stimulus package," ask yourself where that money is actually going. If the drain is high, that stimulus is just going to end up sitting in safes and wallets, doing absolutely nothing for the GDP. The formula is the filter through which all government spending must pass, and lately, that filter has been getting a lot more clogged.