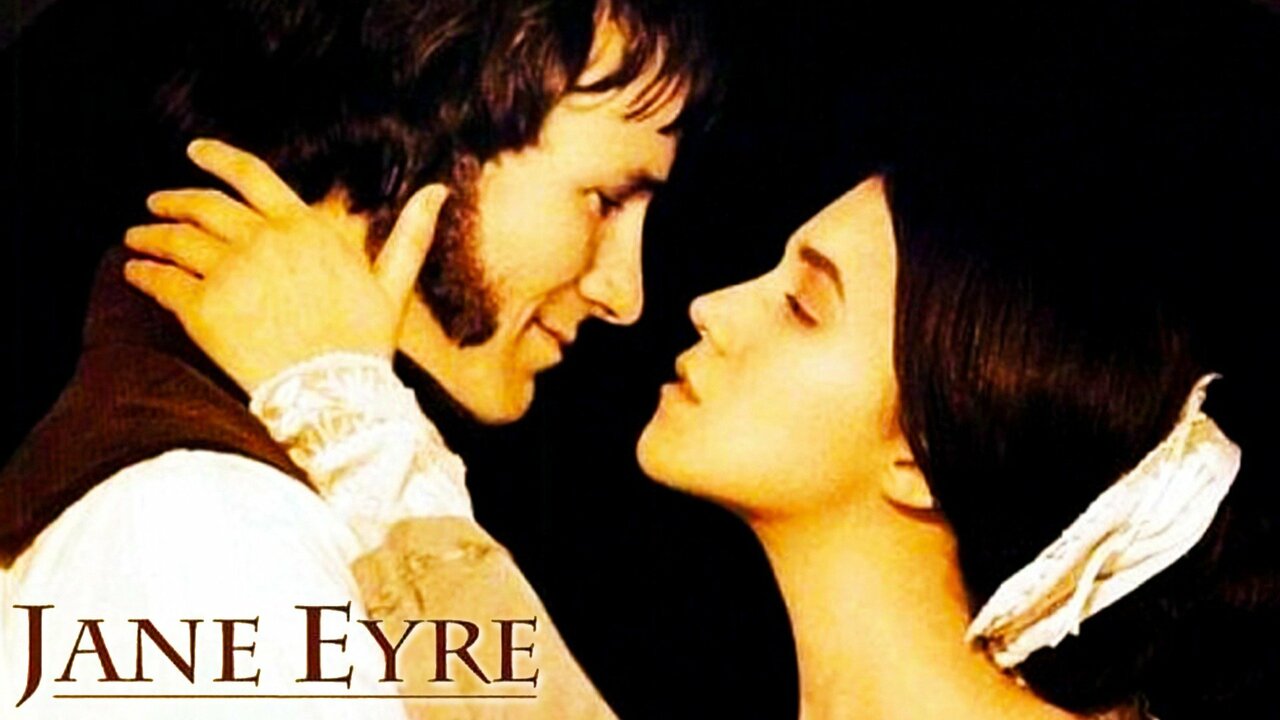

Most people have a "favorite" Jane. If you ask a die-hard Brontë fan, they’ll usually point you toward the 2006 BBC miniseries because it’s long and moody, or maybe the 2011 version because Michael Fassbender looks great in a cravat. But honestly? The Jane Eyre 1996 film directed by Franco Zeffirelli is the one that actually nails the atmosphere of the book.

It’s weird.

People forget about this version. Maybe because it feels a bit more restrained than the gothic-horror vibes we get in modern adaptations, but that’s exactly why it works. It doesn’t try too hard to be "dark." It just is.

When you sit down to watch Charlotte Brontë's story, you're usually looking for that specific mix of grit and repressed Victorian yearning. Zeffirelli, who was already famous for his lush Romeo and Juliet, brought a painterly eye to Thornfield Hall. It’s a gorgeous movie. But it’s also remarkably sad.

What Most People Get Wrong About Charlotte Gainsbourg’s Jane

There was a lot of chatter back in the mid-90s about casting. Charlotte Gainsbourg? A French actress playing the quintessential English heroine? It seemed like a recipe for disaster.

But here’s the thing: Gainsbourg is perfect.

📖 Related: The Brooks and Dunn and Jelly Roll Song: Why Believe Is Finally Having Its Moment

Jane Eyre isn't supposed to be a conventional beauty. She’s described as "plain" and "small." Gainsbourg brings this incredible, quiet intensity to the role that most actresses miss because they’re too busy trying to look like a movie star. She looks like someone who has been hungry her entire life. Not just for food, but for affection.

In the Jane Eyre 1996 film, you really feel her isolation. When she’s standing in those cold, drafty hallways of Thornfield, she looks like she could blow away in the wind. Yet, there’s this steel in her voice. It’s a very internal performance. If you’re looking for big, theatrical crying fits, you won’t find them here. You get something better—real dignity.

William Hurt as Rochester: A Polarizing Choice

Okay, let’s talk about the elephant in the room. William Hurt as Edward Rochester.

Fans of the book are often split down the middle on this one. Rochester is supposed to be "ugly-handsome," fierce, and physically imposing. Hurt plays him with a sort of weary, intellectual melancholy. He’s less of a "Byronic hero" and more of a man who is just exhausted by his own secrets.

Some critics at the time, like Roger Ebert, felt the chemistry was a bit muted. I disagree. It’s just a different kind of chemistry. It’s a meeting of minds. When Hurt and Gainsbourg are together on screen, you aren't watching two teenagers falling in love; you’re watching two lonely adults recognizing themselves in each other. It’s subtle. It’s quiet.

It’s actually quite devastating if you’re paying attention.

The Haunting Visuals of Zeffirelli’s Thornfield

Zeffirelli didn't just film a story; he filmed a house.

The Jane Eyre 1996 film treats Thornfield Hall as a character. It’s not a cartoonish haunted mansion. It’s a real place where the walls feel heavy. The cinematography by David Watkin is stunning, using natural light to make everything feel grounded and historical.

You can almost smell the damp stone and the woodsmoke.

- The Lowood School scenes are genuinely harrowing.

- The transition from young Jane (played by a very young Anna Paquin) to adult Jane is one of the most seamless in cinema.

- The costumes by Jenny Beavan actually look like clothes people lived in, not just museum pieces.

Anna Paquin won an Oscar for The Piano just a few years before this, and her performance as young Jane is foundational. She captures that "rebellious slave" energy that Brontë wrote about so vividly. When she screams at Mrs. Reed, you feel the years of suppressed rage. It sets the stage for everything Gainsbourg does later.

Why the Script Changes Actually Make Sense

Look, every adaptation of a 500-page book has to cut stuff. It's inevitable.

The Jane Eyre 1996 film moves fast. It’s under two hours. To do that, the screenwriters (Zeffirelli and Hugh Whitemore) had to trim the fat. They condensed the Rivers family subplot significantly. For some, this is a crime. For others, it’s a blessing.

The "St. John Rivers" portion of the book can feel like a slog to some readers. By shortening it, the film keeps the focus entirely on Jane’s emotional journey and her eventual return to Rochester.

Does it lose some of the religious nuance of the novel? Yes. But it gains a streamlined, emotional thrust that makes the ending hit harder. It’s a trade-off.

The Sound of Silence and the Score

Alessio Vlad and Claudio Capponi wrote the score, and it’s one of the most underrated soundtracks of the 90s. It’s not sweeping and orchestral in a way that overwhelms the dialogue. Instead, it’s lonely. There are these recurring motifs on the piano and strings that feel like they’re echoing through a big, empty house.

In many scenes, there’s no music at all. Just the sound of footsteps on gravel or the wind in the trees.

This silence is crucial. It builds the tension. When Jane hears that weird, high-pitched laugh coming from the attic, the lack of a "scary movie" soundtrack makes it feel much more grounded and terrifying. It’s psychological.

Comparing the 1996 Version to the Rest

If you’re trying to decide which version to watch, here is the breakdown of where the Jane Eyre 1996 film sits in the pantheon of adaptations:

The 1943 Orson Welles version is pure film noir. It’s moody and expressionistic, but it feels like a Hollywood stage play.

The 2006 BBC version is the most faithful to the text. It has the luxury of time. If you want every single scene from the book, go there.

The 2011 Cary Fukunaga version is the most "Gothic." It’s dark, foggy, and very stylish. It leans into the horror elements.

The 1996 version? It’s the most human. It feels like a real story about real people in a real time. It’s not trying to be a horror movie or a prestige TV epic. It’s just a beautifully acted, elegantly directed piece of cinema that respects the source material without being enslaved by it.

How to Best Experience the Film Today

To really appreciate what Zeffirelli was doing, you have to watch this in a dark room. No distractions.

The film relies so much on shadows and facial expressions. If you’re scrolling on your phone, you’ll miss the way Gainsbourg’s eyes change when Rochester is in the room. You’ll miss the subtle production design that shows the decay of the Rochester estate.

Practical Steps for Fans and Students:

- Watch the opening sequence closely: Pay attention to how Anna Paquin’s Jane moves. She is a creature of survival. This explains why adult Jane is so guarded.

- Compare the "Proposal Scene": Read the chapter in the book first, then watch how Hurt and Gainsbourg handle it. Notice the lack of shouting. It’s all in the subtext.

- Look at the light: Notice how the lighting shifts from the cold, blue tones of Lowood to the warmer, firelit tones of Thornfield, and then to the harsh, bright light of the moorlands. It’s a visual map of Jane's psyche.

- Check the supporting cast: Don't sleep on Joan Plowright as Mrs. Fairfax. She brings a warmth and a "normalcy" to the house that makes the eventual revelation of Bertha Mason even more shocking.

The Jane Eyre 1996 film remains a masterclass in how to adapt a classic. It doesn't need gimmicks. It doesn't need a modern soundtrack. It just needs two great actors and a director who understands that sometimes, the quietest moments are the loudest.

📖 Related: Why the Main Characters of The Little Mermaid Still Captivate Us Decades Later

If you’ve skipped this one because you thought it looked too "traditional," give it another look. It’s much sharper and more haunting than you remember. It captures that specific Brontë loneliness—the kind that stays with you long after the credits roll.