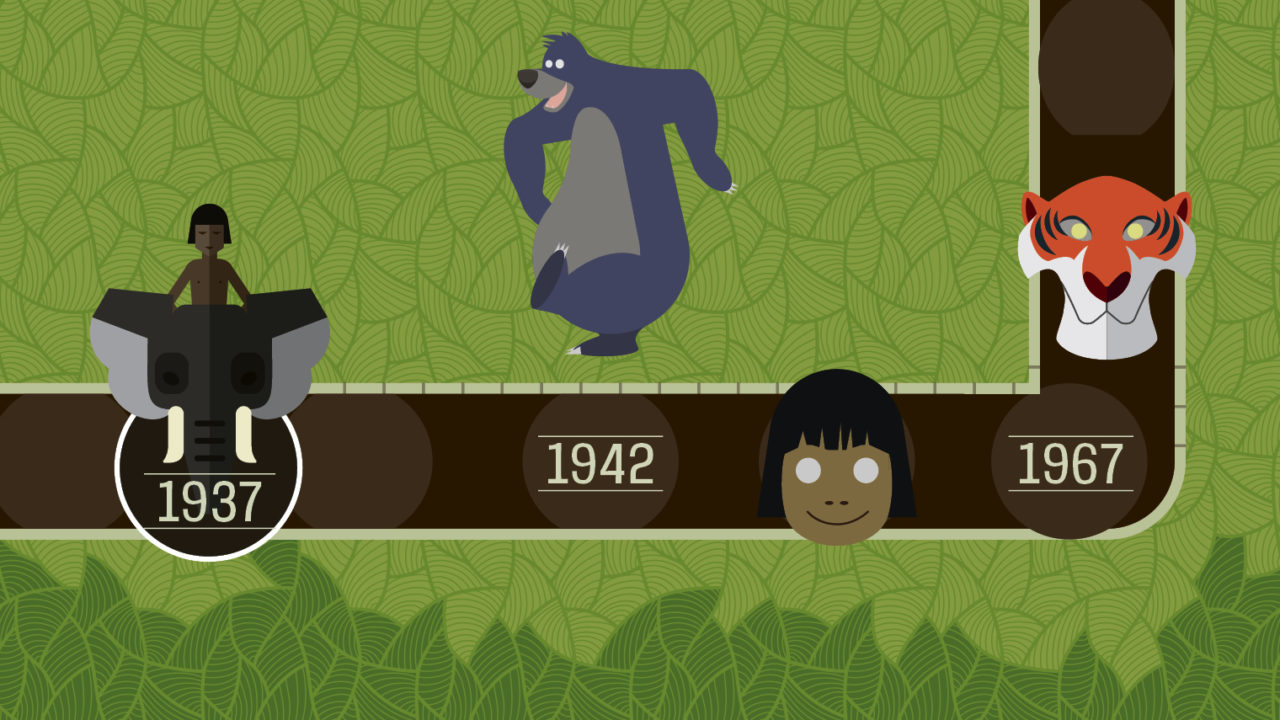

Disney was in a weird spot in the mid-sixties. Walt was still there, but things were shifting. People often forget that The Jungle Book was actually the last film Walt personally oversaw before he passed away in 1966. It’s heavy when you think about it. But the real magic, the thing that actually saved the studio from a creative slump, was the jungle book cast 1967. Before this movie, Disney mostly used professional voice actors—the chameleons who could do fifty voices but nobody knew their names. This film flipped the script. They started casting "personalities." They wanted the character to be the actor.

It worked.

Honestly, it worked so well that it basically became the blueprint for every DreamWorks and Pixar movie you see today. If you look at Baloo, you don't just see a bear. You see Phil Harris. That was entirely intentional.

The Gamble on Personality

Most people assume animated movies are drawn first and voiced later. Not here. For the jungle book cast 1967, the animators actually watched the actors in the recording booth. They sketched the way Phil Harris cocked his head or how Sebastian Cabot moved his jaw.

Phil Harris was a huge risk. He was a radio star, known for The Jack Benny Program, and he had this raspy, jazz-soaked voice that didn't exactly scream "innocent children’s fable." But Walt loved it. He saw the warmth. When Harris was cast as Baloo, the character transformed from a strict teacher—which is how Rudyard Kipling wrote him—into a "jungle bum." It changed the entire vibe of the movie. You can feel that laid-back, 1960s cool every time Baloo opens his mouth to sing "The Bare Necessities."

Then you have Sebastian Cabot as Bagheera. He was the perfect foil. Cabot was famous for Family Affair, and he brought this sophisticated, almost weary dignity to the black panther. The chemistry between a radio comedian and a British character actor shouldn't have worked, yet it’s the heart of the film.

The Kids and the Vultures

Mowgli was voiced by Bruce Reitherman. If that last name sounds familiar, it’s because his dad, Wolfgang Reitherman, was the director. It was a family affair. Bruce wasn't a professional child actor with a fake stage voice; he sounded like a real, slightly defiant kid. That grounded the movie. It kept it from floating off into "too cute" territory.

Speaking of floating off, let's talk about the Vultures. Everyone knows the rumor. The Vultures were supposed to be The Beatles. It’s one of those bits of trivia that everyone repeats at parties. It’s actually true that Disney’s team approached them. Brian Epstein, their manager, liked the idea. John Lennon? Not so much. He reportedly told Epstein to tell Walt Disney that he should hire Elvis Presley instead.

So, the animators kept the moptop haircuts and the Liverpudlian accents, but they filled the roles with guys like J. Pat O'Malley and Digby Wolfe. It’s a weird time capsule. You have these birds that look like the Fab Four singing a barbershop quartet song. It shouldn't make sense, but in the context of 1967, it's perfect.

The Villains: Sanders and Prima

You can't talk about the jungle book cast 1967 without Shere Khan. George Sanders was the only choice. Period. He had this "urbane villain" thing down to a science. Sanders didn't scream. He didn't need to. His voice was like velvet dipped in acid. When he says, "I'll give you till the count of ten," you actually believe he's going to murder a child. It’s terrifying because it’s so calm.

🔗 Read more: Why the cars used in the Fast and the Furious still drive car culture twenty years later

And then there’s King Louie.

Louis Prima brought an energy that was almost too big for the screen. There’s a persistent myth that the role was meant for Louis Armstrong, but Disney was worried about the optics of casting a Black man as a monkey, which was a valid concern given the era's racial tensions. Prima, an Italian-American jazz legend, took the role and ran with it. The recording sessions for "I Wan'na Be Like You" were legendary. Prima and his band were literally dancing around the microphones. The animators couldn't help but put those movements into the monkeys.

Why This Specific Cast Still Matters

If you watch a modern Disney movie, you’re looking for the celebrity. You’re looking for The Rock or Awkwafina. That lineage starts here. The jungle book cast 1967 proved that if you hire a person with a distinct "soul" in their voice, the animation becomes secondary to the performance. It becomes a collaboration.

Sterling Holloway as Kaa is another prime example. Holloway had that airy, whistling voice that he used for Winnie the Pooh. Using that same voice for a predatory snake was a stroke of genius. It made Kaa hypnotic rather than just scary. It added layers.

The Technical Reality of the 1960s

Recording wasn't what it is now. They didn't have infinite tracks. The actors often worked together, which is why the dialogue feels so snappy. When Baloo and Bagheera argue, it feels like two old friends because Harris and Cabot were often in the same room. They could riff.

- Phil Harris (Baloo): The soul of the film.

- Sebastian Cabot (Bagheera): The straight man.

- George Sanders (Shere Khan): The ultimate aristocrat of evil.

- Sterling Holloway (Kaa): The master of the "hiss."

- Louis Prima (King Louie): The king of the swing.

It’s a tight list. There isn't a single weak link in the bunch. Even the minor roles, like Verna Felton as the elephant matriarch, Winifred, carry weight. Felton was a Disney veteran, having voiced everyone from the Fairy Godmother to the Queen of Hearts. This was her final role, too.

Addressing the Kipling Controversy

We have to be honest: the 1967 movie is barely "The Jungle Book." If you read Kipling’s original stories, they are dark. They are about the law of the jungle, blood, and survival. Walt Disney famously told his lead writer, Larry Clemmons, "The first thing I want you to do is not to read the book."

He wanted the movie to be fun. He wanted the jungle book cast 1967 to carry the emotion, not the heavy philosophy of the source material. Some fans of the book hated it. They felt it "Disney-fied" a masterpiece. But the reality is that the movie created its own legacy. It became a piece of 60s pop culture that happens to have animals in it.

The Legacy of the Sound

The music and the voices are inseparable. You can't hear "The Bare Necessities" without picturing Phil Harris's specific growl. The Sherman Brothers wrote most of the songs, and they specifically wrote them for these actors. They knew Prima could handle the scat-singing. They knew Harris could handle the patter.

This wasn't just casting; it was tailoring.

When people search for the jungle book cast 1967, they are often looking for a sense of nostalgia, but they are also looking for why it feels "different" from Cinderella or Snow White. The difference is the humanity. These aren't archetypes. They are people in fur suits.

Actionable Insights for Animation Fans

If you want to truly appreciate what happened in 1967, don't just re-watch the movie. Do these three things to see the "seams" of the craft:

- Watch the "I Wan'na Be Like You" sequence on mute. Look at the way King Louie moves. You can see Louis Prima’s stage presence in every frame. The way the fingers move, the way the body bounces—it's 100% jazz performance captured in ink.

- Listen to Phil Harris’s radio work. If you find old episodes of The Phil Harris-Alice Faye Show, you’ll realize he isn’t "doing a voice" for Baloo. He is Baloo. It makes you realize how bold it was for Disney to cast a guy who was essentially playing himself.

- Compare Shere Khan to George Sanders’ role in All About Eve. You’ll see that the menace comes from the same place: a deep-seated boredom with everyone else's inferiority. It’s a masterclass in how to voice a villain without ever raising your voice.

The 1967 cast didn't just voice a movie; they saved a studio. They proved that animation could be "cool," "hip," and "modern" even while telling a story set in the middle of a jungle. It was the end of an era for Walt, but the beginning of the personality-driven animation age we are still living in.