You know that feeling when you're reading a script and you can almost smell the damp, grimy air of the setting? That’s Skid Row. If you've ever flipped through the little shop of horrors play script, you know it’s not just a goofy story about a giant plant. It’s actually a pretty dark exploration of greed, desperation, and what happens when you’re willing to do anything to get out of a dead-end life. Most people just think of the catchy songs or the 1986 Rick Moranis movie, but the actual stage text—the one licensed through Music Theatre International (MTI)—is a different beast entirely. It’s meaner. It’s faster. And honestly, the ending is way more depressing than the Hollywood version most people grew up with.

The show, with music by Alan Menken and lyrics/book by Howard Ashman, basically changed how we think about Off-Broadway musicals. It took a low-budget 1960 Roger Corman horror flick and turned it into a soulful, 1960s rock-and-roll tragedy.

The Anatomy of the Little Shop of Horrors Play Script

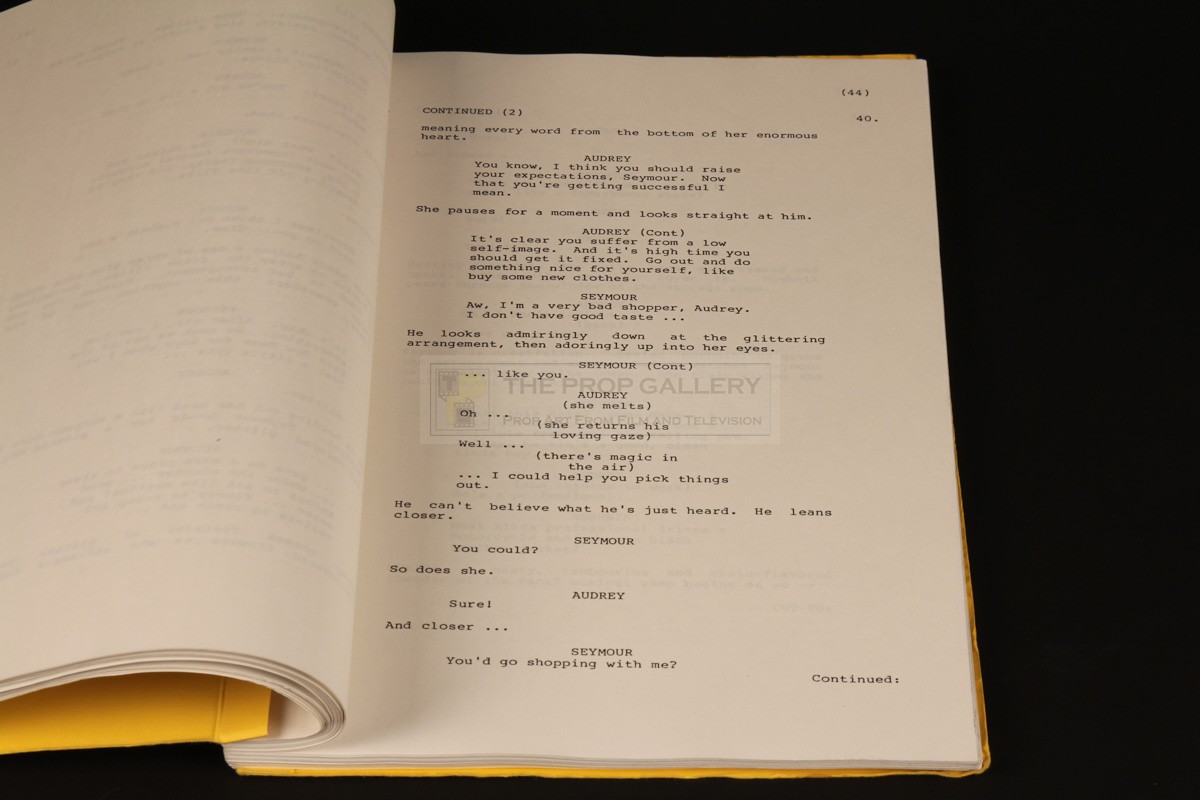

When you look at the script, the first thing you notice is the tone notes. Ashman was very specific. He didn't want this to be played as a "spoof." If the actors wink at the audience, the whole thing falls apart. The stakes have to be real. Seymour Krelborn isn't just a nerd; he's a man who has been physically and emotionally abused by Mr. Mushnik for years. Audrey isn't just a ditzy blonde; she’s a survivor of domestic violence who genuinely believes she doesn't deserve anything better than a "somewhere that’s green" in a tract house.

The dialogue is snappy. It moves like a comic book. You'll see these short, staccato exchanges between Seymour and the plant, Audrey II.

The plant’s lines are written with a specific rhythm that leans heavily into rhythm and blues. It’s seductive. It starts small. In the early pages of the little shop of horrors play script, the plant—referred to as "Twoy"—doesn't even speak. It just wilts. But once it tastes blood? The script shifts. The language becomes more demanding. "Feed me!" isn't just a catchphrase; it’s a command that represents Seymour’s shrinking moral compass.

Why the Stage Ending is a Total Gut Punch

If you’ve only seen the theatrical cut of the 1986 film, you’re probably used to the "Happy Ending." Seymour saves Audrey, they blow up the plant, and they move to the suburbs.

📖 Related: Where Can I Watch Star Trek Voyager: What Most People Get Wrong

The stage script hates you more than that.

In the actual little shop of horrors play script, everyone dies. Audrey is eaten. Seymour is eaten. Even the three street urchins—Crystal, Ronnette, and Chiffon—come out at the end to tell the audience that the plant's offspring are being sold across America. The final stage direction usually involves the plant vines growing out over the audience. It’s a warning. It’s about the "Eat the World" mentality. The script explicitly calls for a "Don't Feed the Plants" finale that is loud, aggressive, and meant to leave the audience feeling a little bit complicit.

The difference is huge. The movie (at least the theatrical version) is a romance. The play script is a cautionary tale about capitalism.

The Characters as Written

- Seymour: The script describes him as a "well-meaning" but "disheveled" orphan. He’s not a hero. He’s a guy who makes a series of increasingly horrific compromises.

- Audrey: Her character notes emphasize her "low self-esteem." It’s heartbreaking to read her lines on the page because her aspirations are so tiny. She just wants a toaster and a fence.

- Orin Scrivello, D.D.S.: The dentist is the script's primary antagonist (aside from the plant). The dialogue for Orin is filled with "chuckle-frights"—he’s a sadist. What’s interesting is that the script often suggests the actor playing Orin also play all the other walk-on roles, like the guy from NBC or the agent from William Morris. It creates this sense that the "outside world" is all just different faces of the same exploitative machine.

- Audrey II: This is a puppet role, but the script treats it like a lead actor. The "Voice of the Plant" is usually situated off-stage or in the pit, while the puppeteer works on-stage. The synchronization is key. If the lips move half a second after the words "Suppertime," the magic is gone.

The Technical Challenges Most People Miss

Reading the script is one thing. Producing it is a nightmare. A fun nightmare, but a nightmare nonetheless. The little shop of horrors play script requires four different versions of the Audrey II puppet.

🔗 Read more: Why That Viral Monkey Driving Golf Cart Video Isn't What You Think

- Pod 1: A small hand-held pot.

- Pod 2: A larger version where the actor’s arm becomes the neck.

- Pod 3: A massive puppet where the actor sits inside and operates it like a giant jaw.

- Pod 4: A room-filling behemoth that can actually "swallow" actors.

The script has specific cues for "feeding" where the actors have to disappear into the plant’s gullet. It requires a trap door or a very clever use of the puppet's structure. If you’re a high school drama teacher looking at this script, the first thing you check is the budget for the puppets. You can’t just wing it.

The Music as Narrative

We can’t talk about the script without the score. The lyrics are baked into the dialogue. "Downtown (Skid Row)" isn't just an opening number; it’s world-building. It establishes the "light" in the script—the dream of escaping—and the "dark"—the reality of the gutter.

Notice how the street urchins act as a Greek Chorus. They are the only characters who move between the "real" world of the shop and the "theatrical" world of the songs. They provide the exposition that the little shop of horrors play script needs to keep its breakneck pace. Without them, the story would feel too heavy. They provide the "Shoop-da-doo" that makes the murder digestible.

🔗 Read more: Why There’s Still Something About Mary After All These Years

How to Approach the Text Today

If you’re studying the little shop of horrors play script for a production or a class, look at the 1950s/60s B-movie tropes it uses. It’s a pastiche. It uses "Faustian" bargain elements—Seymour sells his soul for fame and a girl—but wraps it in doo-wop.

Don't ignore the darker subtext. The script deals with poverty. It deals with people who feel invisible. Mushnik only starts caring about Seymour when Seymour becomes a meal ticket. That’s a stinging indictment of how we value people based on their productivity or what they "own."

Actionable Steps for Actors and Directors

- Focus on the "Why" of the Plant: Before you start blocking, decide what the plant represents to your Seymour. Is it his ambition? Is it his fear? The plant’s personality should be a mirror of Seymour’s internal state.

- Diction over Volume: The lyrics in this script are dense. If the audience misses one "lookout, here comes Audrey Two," they lose the plot.

- The Dentist's Death: This scene in the script is a masterclass in dark comedy. It’s a monologue interrupted by a gas mask. The timing has to be precise. The actor playing Orin needs to balance the physical comedy of the nitrous oxide with the genuine threat he poses to Audrey.

- Research the 1982 Off-Broadway Roots: Look at the original production photos from the Orpheum Theatre. It was scrappy. It was intimate. Trying to make the show too "glossy" often kills the heart of the script.

Whether you're a collector of scripts or someone looking to stage the show, the little shop of horrors play script remains a blueprint for how to balance camp with genuine pathos. It’s a reminder that even the weirdest stories—like a singing venus flytrap from outer space—can tell us something deeply uncomfortable about the human condition.

If you're planning on performing this, your first move should be to secure the rights through MTI and look into the specific technical riders for the puppets. You can't just build these things overnight; they require a specific type of engineering to ensure the "swallowing" of characters like Mushnik and Orin looks believable and is safe for the actors. Dive into the 1960s soul and Motown influences to get the vocal style right, and remember: keep it grounded. The more seriously the actors take the situation, the funnier and more tragic the show becomes.