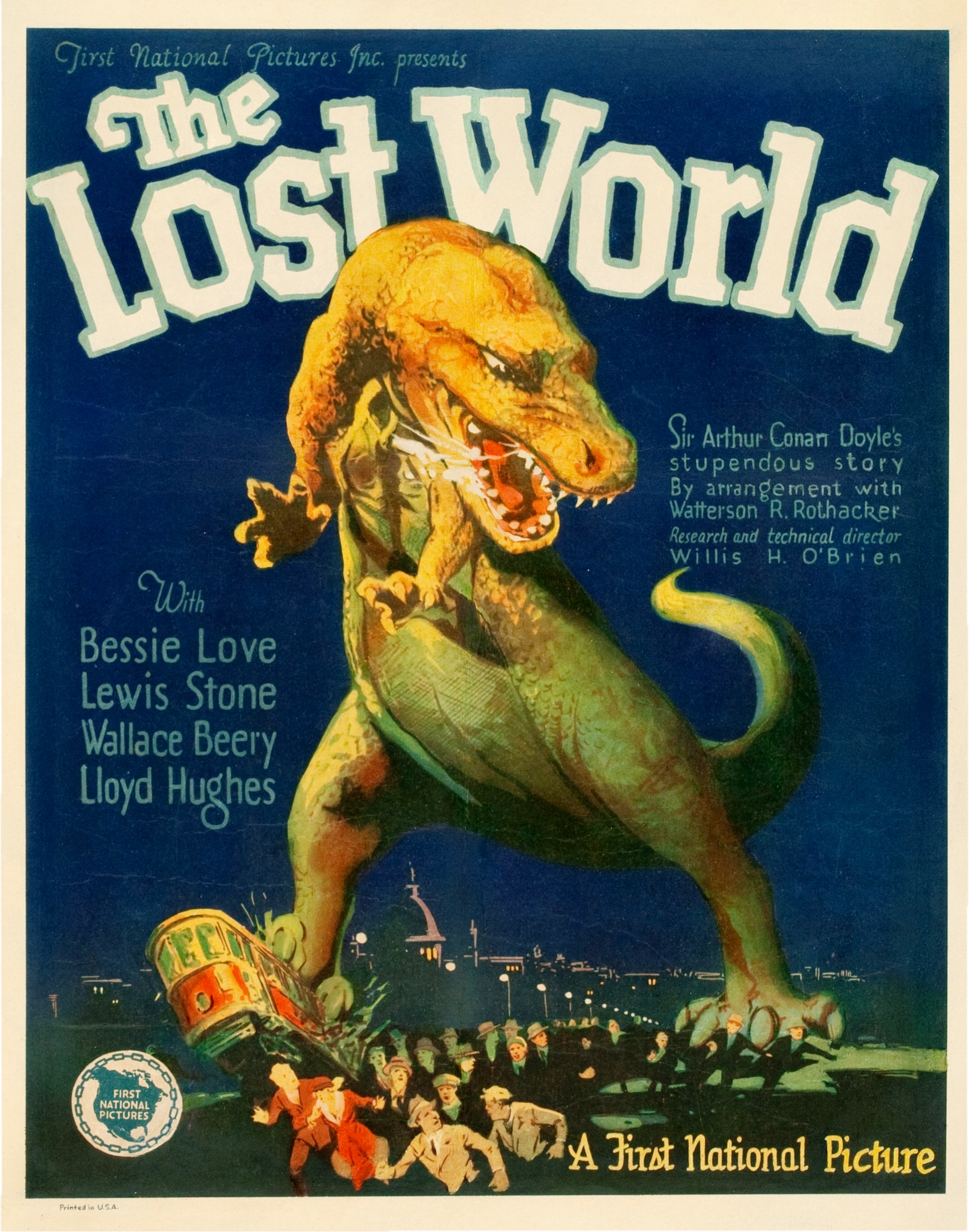

Stop thinking about CGI for a second. Forget the polished, billion-pixel textures of modern blockbusters where dragons and superheroes look flawlessly integrated into 4K landscapes. Instead, try to imagine sitting in a dark theater in 1925. You’re watching The Lost World 1925, and for the first time in human history, a Brontosaurus isn't just a drawing in a textbook. It is moving. It is breathing. It is destroying a London street.

People actually panicked.

This wasn't just a movie; it was a fundamental shift in how we perceive reality through a lens. When Willis O’Brien brought Arthur Conan Doyle’s prehistoric plateau to life, he wasn't just making a "monster movie." He was inventing the visual language of the impossible. Honestly, most people today see old black-and-white films and think "slow" or "dated," but The Lost World 1925 has a raw, jittery energy that modern digital effects often lack. There is a weight to those clay models. You can almost feel the fingerprints of the animators on the rubber hides of the Allosaurus.

The Man Who Tricked Houdini

Before the film even hit theaters, there was this legendary moment involving Harry Houdini and a meeting of the Society of American Magicians. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the guy who wrote Sherlock Holmes and the original Lost World novel, showed up with a reel of test footage. He didn't tell anyone what it was. He just played it.

✨ Don't miss: Daryl Dixon: Why We Still Can’t Let Go of The Walking Dead’s Best Mistake

The magicians were floored.

They couldn't figure out the trick. Houdini, the master of deception, was genuinely baffled by the sight of prehistoric beasts interacting with each other in what looked like a real jungle. Doyle later admitted it was just a "psychological experiment," but the impact was clear: stop-motion was the new magic.

The technical wizardry behind The Lost World 1925 was spearheaded by Willis O'Brien. If that name sounds familiar, it should. He’s the mentor to Ray Harryhausen and the man who eventually gave us King Kong in 1933. But this 1925 epic was his true proof of concept. He used inflatable bladders inside the dinosaur models to simulate breathing. Think about that level of detail in 1925. They weren't just moving legs; they were simulating the biological functions of extinct animals.

Forget Jurassic Park—This Was the Original Dino-Sensation

Most modern audiences think Steven Spielberg invented the "dinosaur rampaging through a city" trope. Not even close. While the novel ends with a Pterodactyl escaping into London, the film version of The Lost World 1925 turns the dial to eleven. It gives us a Brontosaurus (or Apatosaurus, depending on which paleontologist you’re arguing with) causing absolute carnage at the Tower Bridge.

It was spectacular.

The scale was unprecedented. First National Pictures poured a massive budget into this—roughly $700,000, which was an eye-watering sum back then. They needed to justify the cost by creating something that looked "real."

The Puppet Master’s Secret Sauce

O'Brien’s technique involved a lot of trial and error. He used metal armatures—essentially ball-and-socket skeletons—covered in sponge rubber and clay. The challenge wasn't just making them move; it was the lighting. If a single light shifted between frames, the whole sequence would flicker and ruin the illusion.

- The Models: Usually about 6 to 12 inches tall.

- The Frame Rate: Shot frame-by-frame, a painstaking process that took months for just a few minutes of footage.

- The Environments: Miniature sets filled with real moss, tiny trees, and painted backdrops to create depth.

One of the coolest, albeit kind of gross, facts about the production is how they handled "blood." During the fight scenes between the dinosaurs, they used chocolate syrup or thick oils to represent wounds. In black and white, it looked visceral and dark. It gave the fights a sense of consequence that you didn't see in the "man in a rubber suit" movies that came decades later.

Why the Characters Sorta Matter (But Not Really)

Let’s be real. Nobody is watching The Lost World 1925 for the nuanced romantic subplots. You’re there for Professor Challenger. Wallace Beery played the role with this aggressive, bushy-bearded energy that perfectly captured the "mad scientist but he’s actually right" vibe from the book.

The plot follows the standard expeditionary template. Challenger claims dinosaurs exist on a plateau in South America. Everyone calls him a crank. He leads a team—including a skeptical rival, a big-game hunter, and a romantic lead—into the Amazon. They find the plateau, get stuck, and realize they are at the bottom of the food chain.

What’s interesting is how the film handles the "Ape-Man" subplot. In the original 1925 cut, there was a lot more focus on the indigenous creatures and the missing link characters. Over the decades, various cuts of the film were lost or edited down, and for a long time, the full version was considered a "lost" masterpiece itself. It wasn't until the 1990s and early 2000s that restorations using footage from international archives brought back much of the original runtime.

The Technical Nightmare of the 1920s

Imagine being an editor in 1925. You’re dealing with highly flammable nitrate film. You’re trying to sync up live-action footage of actors looking up in terror with miniature footage of a dinosaur that was filmed weeks apart.

This was the birth of the "split-screen" and "matte" shots.

To get the actors and the dinosaurs in the same frame, they would mask off part of the camera lens, film the actors, then rewind the film and expose the other half with the stop-motion footage. It required mathematical precision. If the actor’s eye line was off by an inch, the whole thing looked ridiculous.

But it worked.

The scene where the expedition watches the spectacle of a volcanic eruption while dinosaurs flee in the background is a masterclass in composition. It’s chaotic. It’s messy. It feels like a documentary from a nightmare.

Why It Still Matters in the Age of AI and CGI

We’ve reached a point where digital effects are so "perfect" they’ve become boring. There’s a certain sterile quality to a modern Marvel fight. You know it’s a computer. But with The Lost World 1925, there’s a tangible soul to the movement. Because it was hand-animated, there are tiny imperfections—a slight stutter in a tail flick, a momentary tremble in a limb.

These "errors" actually make the creatures feel more alive. They feel like they exist in physical space because they did exist in physical space. They were physical objects being manipulated by human hands.

Furthermore, this movie set the blueprint for the "Eco-Thriller." It tapped into that primal human fear: what if we aren't the masters of the earth? What if there are pockets of the world where the old rules still apply? It’s a theme that travels directly from Doyle to Michael Crichton and beyond.

What Most People Get Wrong About the 1925 Version

A common misconception is that the movie was a flop or just a "cult" hit. Actually, it was a massive commercial success. It proved that "spectacle" was a viable business model for Hollywood. It also established the "Monster as a Tragic Hero" trope long before Kong fell from the Empire State Building. When the Brontosaurus falls into the Thames at the end, there’s a genuine sense of sadness. It’s a creature out of time, destroyed by a world it doesn't understand.

Another weird myth is that they used real "monsters" (like lizards with fins glued on). While later films like One Million B.C. (1940) used that lazy trick, The Lost World 1925 was almost entirely stop-motion. They respected the craft. They wanted to build something from scratch.

Actionable Insights for Film Buffs and Creators

If you’re a fan of cinema history or a creator looking for inspiration, there are a few things you should actually do to appreciate this film properly.

📖 Related: Why Mr and Mrs Smith Season 1 Isn’t the Remake You Expected

- Watch the 2017 Restoration: Don't settle for a grainy YouTube upload from 2008. The Lobster Films restoration is the definitive version. It uses the best available elements and restores the original tinting (blue for night, red for fire). It changes the experience entirely.

- Study the Silhouette: Notice how O'Brien uses silhouettes to hide the limitations of his models. If you're a photographer or filmmaker, look at how he uses "rim lighting" to separate the dark dinosaurs from the dark jungle backgrounds. It's a masterclass in lighting for low-contrast environments.

- Read the Original Doyle Novel: Compare how the movie diverges. The book is much more of a philosophical debate between Challenger and Summerlee. The movie is—rightfully so—an action-adventure. Seeing where the "Hollywood-ization" began is fascinating.

- Look for the "Ghost" Frames: If you watch closely, you can sometimes see the faint outlines of the animators' tools or even their hands in the very early test shots that survived. It’s a reminder that this was a labor of literal blood, sweat, and clay.

The Lost World 1925 isn't just a museum piece. It’s the DNA of modern entertainment. Every time you see a creature on screen that makes you gasp, you're seeing the legacy of Willis O'Brien and a rubber dinosaur in a miniature jungle. It taught us that the camera doesn't just record reality—it can invent a new one.

To truly understand the history of special effects, you have to start here. Go find the restored silent cut, turn off the lights, and imagine it’s 1925. The roar you hear isn't digital; it’s the sound of an entire industry being born.

Next Steps for Deep Exploration:

- Locate a copy of the George Eastman Museum restoration for the most complete viewing experience.

- Research the work of Willis O'Brien specifically between 1915 and 1925 to see the evolution of his "Dinosauria" shorts.

- Compare the 1925 creature designs to the Charles R. Knight paintings of the era; you'll see how the film served as the first "living" version of the leading paleontological art of the early 20th century.