If you look at a standard map of Svalbard archipelago, it looks like a shattered jigsaw puzzle floating in the dead space between Norway and the North Pole. Most people see a bunch of white blobs and think "glaciers." They aren't wrong, but they're missing the point. Looking at this map isn't just about geography; it’s about understanding a place where the rules of the world don't really apply. You’ve got a landmass roughly the size of West Virginia, yet it’s home to more polar bears than people. It’s a place where you can’t legally be buried because the permafrost will just spit your coffin back out like a bad habit.

Seriously.

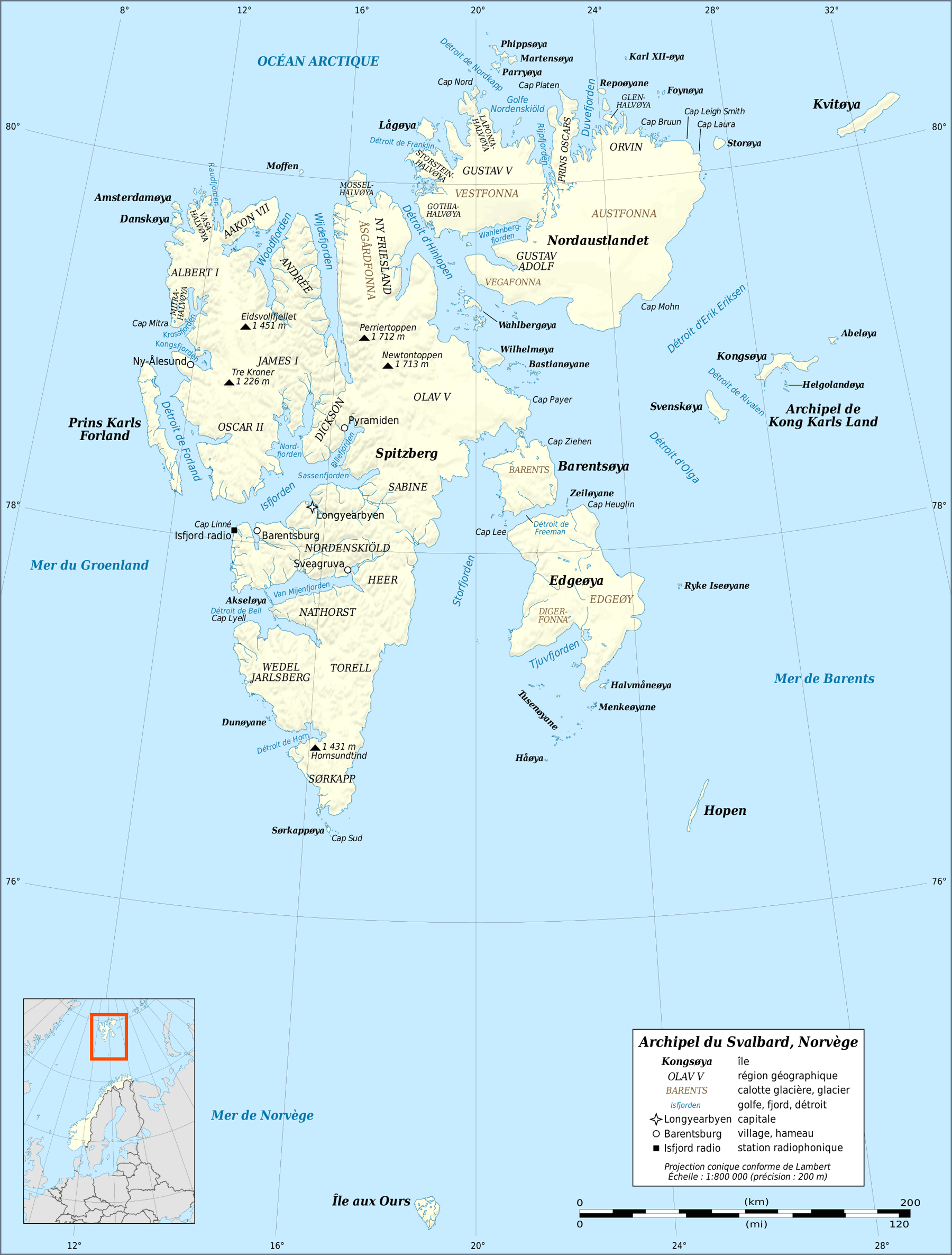

Svalbard is remote. It's the northernmost year-round settlement on the planet. When you pull up a digital map, you’ll notice Spitsbergen is the big island, the heart of everything. But then there’s Nordaustlandet, Barentsøya, and Edgeøya. These names sound like they belong in a Viking saga because, well, they basically do. Willem Barentsz, the Dutch explorer, bumped into this place in 1596 while trying to find a shortcut to China. He didn't find China. He found jagged mountains. That’s actually what "Spitsbergen" means—pointed mountains.

Navigating the Spitsbergen Core

The map of Svalbard archipelago is dominated by Spitsbergen. This is where the action is, if you can call a town of 2,500 people "action." Longyearbyen is the hub. If you’re flying in, you’re landing here. It sits on the south side of Adventfjorden. Most people think they can just wander out of town for a hike. Don't. You need a high-powered rifle for that. The map doesn't show the "polar bear zone" because the entire map is the polar bear zone.

North of Longyearbyen, you’ll see Ny-Ålesund. It’s an old mining town turned into a high-tech research station. It’s one of the cleanest places on Earth in terms of atmospheric data. They’re so strict about radio interference there that you have to turn off your Wi-Fi and Bluetooth miles before you arrive. It’s a total dead zone for your iPhone, which is kinda refreshing but also terrifying if you’re used to being connected.

Then there’s the Russian influence. Look at the map again and find Barentsburg. It’s a Russian coal-mining settlement. It feels like stepping back into the USSR. There’s a bust of Lenin staring out over the icy water. It’s surreal. You have a Norwegian territory governed by the Svalbard Treaty of 1920, which basically says anyone from the signatory countries can live and work there. That’s why you’ll find Thais, Ukrainians, and Filipinos all living in the High Arctic.

The Hidden Depths of the Fjords

The coastline is a mess of fjords. Isfjorden is the big one, slicing into the west side of Spitsbergen. It’s deep. It’s cold. It’s the lifeblood of the islands. Without the North Atlantic Drift—a tail end of the Gulf Stream—these waters would be frozen solid year-round. Instead, the west coast stays relatively accessible while the east side of the archipelago is often choked with sea ice.

If you look at a bathymetric map (the kind that shows what's under the water), you see these massive trenches. They’re underwater highways for whales. Bowheads, belugas, and narwhals hang out in these deep spots.

Nordaustlandet and the Great Ice Caps

Move your eyes northeast on the map of Svalbard archipelago. You hit Nordaustlandet. This isn't a place for casual tourists. It’s dominated by Austfonna, one of the largest ice caps on Earth by area. We’re talking about an ice dome that’s hundreds of meters thick.

Glaciologists like those from the Norwegian Polar Institute spend their lives studying this ice. It’s moving. It’s melting. It’s surging. Sometimes a glacier will just decide to sprint—relatively speaking—moving several meters a day instead of centimeters. This changes the map constantly. What was a solid ice front ten years ago might be a retreating wall today, revealing new islands or bays that weren't there before.

- Austfonna: The monster ice cap.

- Vestenhalvøya: A rugged peninsula with some of the oldest rocks in the region.

- Hinlopen Strait: The treacherous water between Spitsbergen and Nordaustlandet. It’s famous for its bird cliffs, specifically Alkefjellet, where thousands of Brünnich's guillemots nest on basalt towers.

Edgeøya and Barentsøya sit to the southeast. These islands are part of the Søraust-Svalbard Nature Reserve. You can’t just roll up here. Access is heavily restricted to protect the mosses and the reindeer. Svalbard reindeer are different—they’re short, stubby, and kinda look like they’ve been squashed. Evolution decided they didn't need long legs to run from predators because, for a long time, there weren't many.

Why the Map Keeps Shifting

Climate change isn't a "future" thing in Svalbard. It’s a right now thing. The archipelago is warming four times faster than the global average. This makes any printed map of Svalbard archipelago a bit of a lie.

I remember talking to a local guide who mentioned that places once labeled as "permanent ice" are now open water in the summer. This creates a massive headache for the Norwegian Mapping Authority (Kartverket). They use satellites now, obviously, but the physical reality on the ground—or ice—is fluid.

The Global Seed Vault: A Map Within a Map

Hidden on the map near Longyearbyen is a tiny dot that represents the Global Seed Vault. It’s built deep into the permafrost of Platåberget mountain. It’s designed to last thousands of years, acting as a "back-up hard drive" for the world's crops.

Even this had a scare recently. In 2017, unusually warm weather caused some meltwater to leak into the entrance tunnel. It didn't reach the seeds—thankfully—but it was a wake-up call. When the permafrost on your map starts melting, the very foundation of your infrastructure gets shaky.

Practical Tips for Reading the Terrain

If you’re planning to visit or just obsessing over the geography, you need to use TopoSvalbard. It’s the official interactive map provided by the Norwegian Polar Institute. Google Maps is basically useless here once you leave the three main streets of Longyearbyen.

📖 Related: Finding Mumbai on a Map: Why This Pinpoint is So Weirdly Important

- Check the Contour Lines: Svalbard is steep. Those little lines on the map that are packed close together mean you’re looking at a cliff, not a path.

- Understand the Colors: White isn't always snow; sometimes it's "unmapped" or "glacier." Gray usually denotes barren rock. There isn't much green.

- The Scale is Deceptive: Things look close on a screen. In reality, crossing a fjord can take hours in a sturdy RIB boat, assuming the weather doesn't turn.

- Magnetic Declination: If you’re old school and using a compass, the magnetic north is constantly shifting. Up here, the difference between true north and magnetic north is significant.

Honestly, the best way to understand the map of Svalbard archipelago is to realize it's a map of a living, breathing, and unfortunately melting entity. It’s a frontier. There are no trees. No bushes. Just rock, ice, and the occasional tuft of purple saxifrage trying its best to survive.

Actionable Next Steps for Enthusiasts

If you want to go beyond just looking at a screen, here is how you actually engage with this geography:

- Download TopoSvalbard: Skip the generic map apps. The Norwegian Polar Institute’s tool allows you to toggle between historical maps and modern satellite imagery. It’s the only way to see how much the glaciers have actually retreated since the 1930s.

- Study the Treaty Zones: If you're a researcher or looking to work there, read the 1920 Svalbard Treaty. It defines the unique "No-Visa" status of the islands, which is why the map includes such a weird mix of international presence.

- Monitor the Sea Ice: Use the Norwegian Meteorological Institute’s ice charts. These are updated daily and show you where the "map" ends and the navigable ocean begins. This is critical for anyone planning a maritime expedition.

- Focus on Geological Layers: Svalbard contains rocks from almost every geological period. If you’re a rock nerd, look for the stratigraphic maps. You can find dinosaur footprints in the same general vicinity as ancient Caledonian mountain roots.

The archipelago isn't just a destination; it's a warning and a wonder. The map tells a story of discovery, exploitation (whaling and mining), and now, intense scientific observation. Whether you're tracking the movement of a polar bear tagged with a GPS collar or just trying to figure out where the pavement ends in Longyearbyen, respect the scale of the place. It's bigger and colder than your screen makes it look.