If you look at an early map of the South Carolina colony, it basically looks like a child’s drawing of a rectangle that someone accidentally spilled coffee on. It’s messy. It’s wildly inaccurate by modern GPS standards, yet these maps were the most expensive, dangerous, and high-stakes documents of the 18th century. They weren't just paper. They were land claims. They were legal weapons used to push back against Spanish Florida or to slice up indigenous territories without a second thought.

History is messy.

South Carolina started as a massive "Proprietary" slice of pie given to eight of King Charles II's favorite buddies—the Lords Proprietors. In 1663, the charter technically claimed everything from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Seriously. They thought they owned California. Of course, nobody had actually walked that far, so the early maps are mostly just detailed coastlines with a big, empty "Who knows?" written over the interior.

The Chaos of the First Coastal Surveys

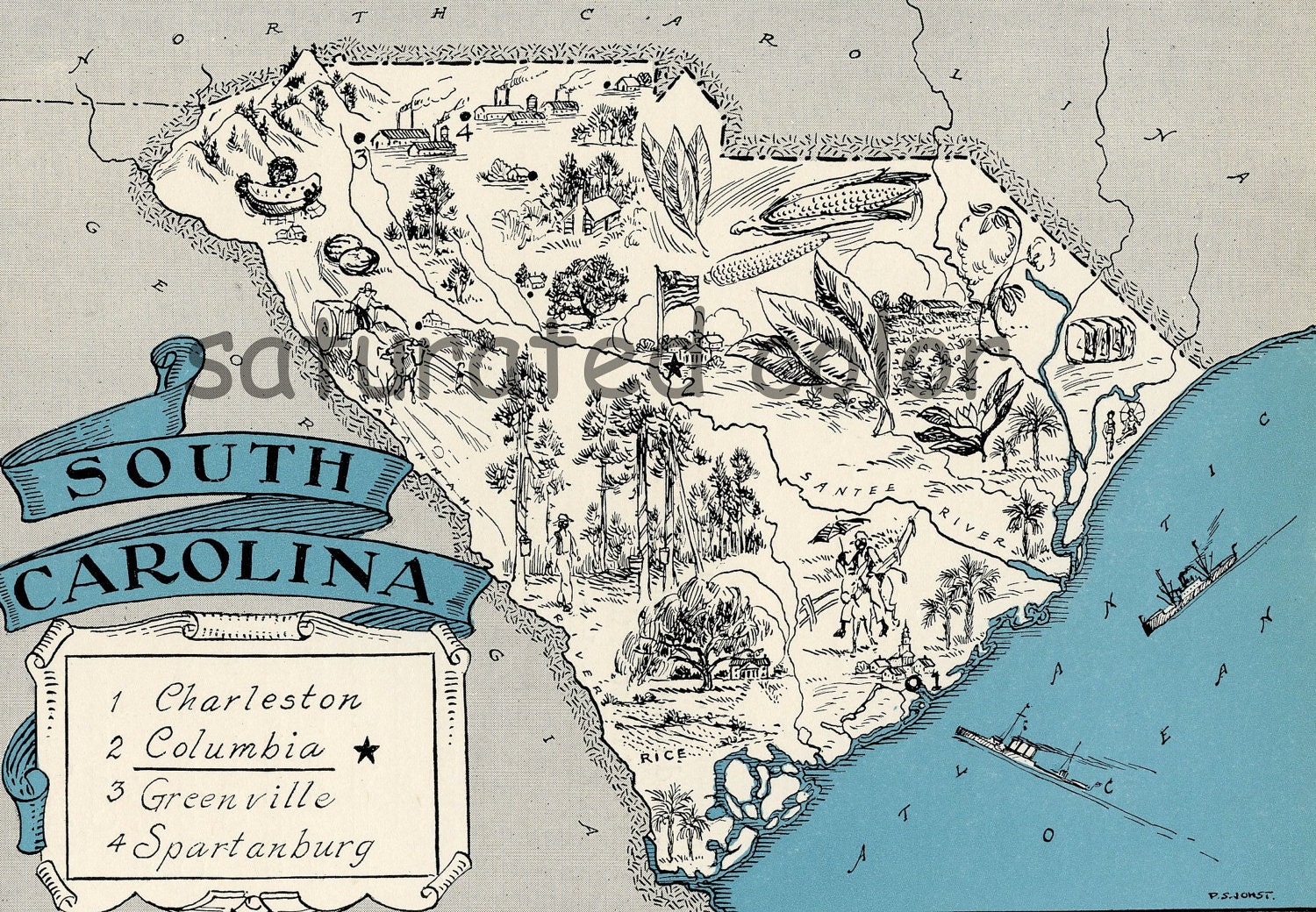

The earliest maps, like the ones by Nicholas Sanson or the later, more famous Mouzon map, were obsessed with Charleston. Or "Charles Town," as it was then. You see, the map of the South Carolina colony was driven entirely by rice and indigo. If a piece of land couldn't grow "Carolina Gold" rice, the mapmakers barely bothered to name the creeks.

Cartography was a rich man's game.

💡 You might also like: Red Black and White Christmas Tree Ideas That Actually Work

Take the 1711 Edward Crisp map. It’s iconic. It shows the fortifications of Charleston during a time when the settlers were terrified of a French or Spanish invasion. You can see the tiny little bastions. But look just a few miles inland, and the geography starts to get... creative. They didn't have drones. They had guys with chains and compasses wading through alligator-infested swamps in 100-degree humidity. It’s a miracle they got the coastline right at all, honestly.

Why the Boundaries Kept Moving

The border with North Carolina was a nightmare. For decades, nobody actually knew where one colony ended and the other began. If you lived in the "borderlands," you might tell the South Carolina tax collector you lived in North Carolina to avoid paying, and then tell the North Carolina guy the opposite.

It was a total mess.

The 1737 and 1764 surveys tried to fix this. They wanted a straight line. But because of compass errors—literally just the needle being off by a few degrees—the line ended up with a weird "jog" near the Catawba River. If you look at a modern map today, that weird little notch at the top of South Carolina is a direct result of 18th-century surveyors getting lost in the woods.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Still Obsesses Over Strawberry Pound Cake Bath and Body Works

Reading the Map of the South Carolina Colony Like an Expert

When you study an authentic map of the South Carolina colony, you have to look for what isn't there. Notice the lack of towns? Aside from Charleston, Beaufort, and Georgetown, the map is mostly just names of families. "Bull," "Colleton," "Middleton." These maps were status symbols for the planter elite.

Mapping was a tool of power.

By the mid-1700s, maps started showing "Pathways to the Cherokee Nation." This is where the maps get dark. These lines weren't just for trade; they were blueprints for expansion. When you see a map like the 1775 Henry Mouzon version, you’re looking at the peak of colonial cartography. It was so good that both George Washington and British General Cornwallis used it during the Revolutionary War.

Imagine that. Both sides of a war using the exact same piece of paper to try and kill each other.

The Problem with the "Backcountry"

The maps from the 1750s show a massive shift. Before then, the "Upstate" or Backcountry was basically a blank spot labeled "Desert" or "Savannah." It wasn't actually a desert, obviously. It was just filled with people the British government didn't care about yet—mostly Scots-Irish settlers and Native American tribes like the Cherokee and Catawba.

As the population exploded, the maps got crowded.

Suddenly, you see "Townships" appearing. These were 20,000-acre blocks designed to lure Europeans to the frontier to act as a human buffer between the wealthy coast and the indigenous tribes. Names like Saxe Gotha and Orangeburg start popping up. If you're looking at a map of the South Carolina colony from 1760 versus 1720, the difference is staggering. It goes from a coastal outpost to a sprawling, aggressive plantation state.

How to Find a Real Colonial Map Today

Most people just look at low-res JPEGs on Wikipedia. Don't do that. If you actually want to see the nuance, you need to head to the Library of Congress digital archives or the South Carolina Historical Society.

They have the high-res scans where you can actually see the "hachure" marks—those tiny little lines used to show hills before we had contour lines.

- The 1685 Thornton-Morden Map: This is the "Gold Standard" for early weirdness. It shows the settlement when it was barely a decade old.

- The 1757 William De Brahm Map: De Brahm was a bit of a genius and a bit of a madman. His maps are incredibly detailed, showing the specific soil types. He was obsessed with the science of the land.

- The 1773 James Cook Map: No, not that Captain Cook. This James Cook made a map of South Carolina that was so detailed it actually listed individual mills and taverns. It's basically the 18th-century version of Google Maps.

Why the Colors are Usually Fake

If you see a colorful map of the South Carolina colony for sale on Etsy, the color was probably added recently. Back then, "hand-colored" maps existed, but they were incredibly expensive. Most maps were black ink on heavy rag paper. The paper is actually why so many survived; it’s made of cotton and linen, not wood pulp, so it doesn't turn brittle and yellow like a newspaper from the 1990s.

It’s tough stuff.

💡 You might also like: White Bedroom Furniture Decor: What Most People Get Wrong About the All-White Look

Practical Steps for Researching Carolina Cartography

If you're trying to track down a specific ancestor or a piece of land using these maps, you have to be careful with the scale. "One League" in 1720 might not be what you think it is.

- Check the Scale of Miles: Every mapmaker used a slightly different measurement. Always look for the "Scale of Miles" at the bottom and compare it to a modern topographical map.

- Look for "Plats": While a map of the South Carolina colony shows the whole province, "plats" are the tiny, individual maps of a single farm. The South Carolina Department of Archives and History has thousands of these digitized. That’s where the real detail is.

- Cross-reference with the "Grand Model": Charleston was laid out according to a specific plan called the Grand Model. If your research involves the city, start there before looking at the provincial maps.

- Account for Magnetic North: Remember that the North Pole moves. A line drawn in 1750 using a compass will be off by several degrees if you try to follow it with a compass today.

The map of the South Carolina colony is more than just a piece of history. It’s a record of how people tried to impose order on a landscape that was constantly pushing back. It’s a record of ego, greed, and some seriously impressive math. Whether you're a history buff or just curious about why the state lines look so jagged, these old documents hold the answers. They show a colony trying to figure out exactly what it was—and who it was willing to displace to get there.

To see these details in person, use the Library of Congress "Geography and Map Division" online portal. Search specifically for "South Carolina 1700-1780." You can zoom in deep enough to see the individual ink bleeds from the engraver's plate. It’s the closest thing we have to a time machine.