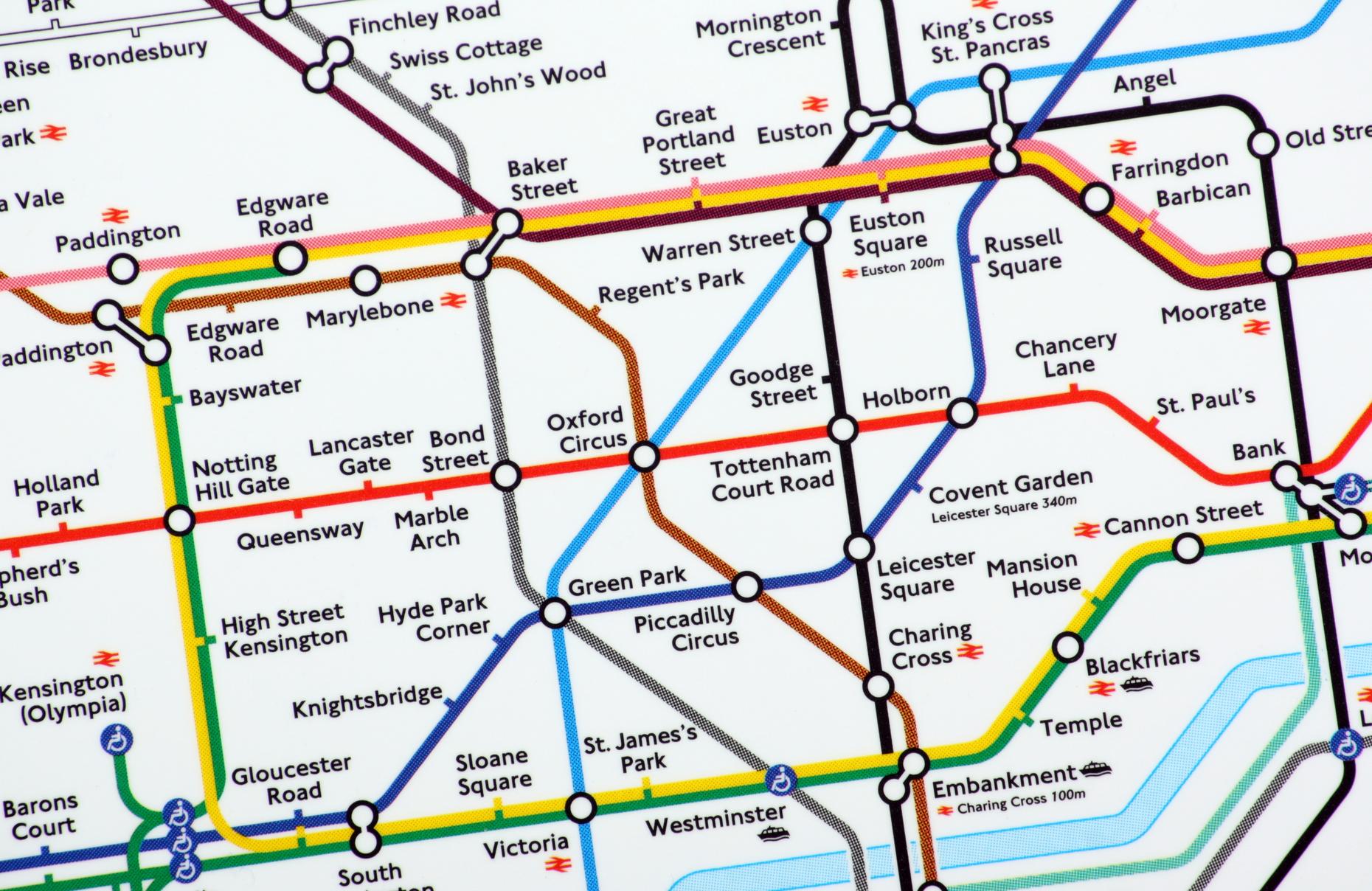

You’re standing at Leicester Square. You need to get to Covent Garden. Naturally, you squint at that iconic grid of primary-colored lines, trace the Piccadilly line for one stop, and prepare to pay £2.80 for the privilege.

Stop.

If you actually follow the map of the tube stations literally, you’re going to waste time. It’s a 250-meter walk. You can see one station from the entrance of the other. But on the map? They look like distinct, distant points on a logic-driven grid. This is the great deception of London. The map is a masterpiece of design, but it is a topographical nightmare. It was never meant to be a mirror of reality. It’s a diagram of a machine.

✨ Don't miss: Why Your Mental Image of a Scene at Sea is Probably Wrong

The Man Who Killed Geography

Harry Beck was a technical draughtsman who got laid off in the 1930s. Before him, the map of the tube stations was a mess of wiggly lines that tried to show exactly where the tunnels went under the streets. It was cluttered. It was confusing. It was, quite frankly, ugly.

Beck had an epiphany: passengers don't care what's happening above ground.

When you’re hurtling through a dark tunnel at 30 miles per hour, do you really need to know that you’re passing under a specific Boots on Oxford Street? No. You just want to know where to change trains. Beck borrowed the logic of an electrical circuit diagram. He simplified everything to verticals, horizontals, and 45-degree diagonals. He turned the chaotic sprawl of London into a clean, tidy rectangle.

The London Passenger Transport Board initially rejected it. They thought it was "too revolutionary." They were wrong. People loved it because it simplified a complex world. But that simplification came at a massive cost to our perception of distance.

Why Your Eyes are Lying to You

Look at the distance between Paddington and Royal Oak. On the map of the tube stations, it looks like a significant journey. In reality, you could throw a stone from one to the other. Conversely, look at the gaps in the outer zones. A tiny jump on the map in Zone 6 might actually represent miles of suburban sprawl.

This distortion creates "ghost journeys." These are trips where people spend twenty minutes underground to travel a distance that would take five minutes on foot.

Take Charing Cross and Embankment. They are practically on top of each other. Yet, every single day, tourists descend into the depths of the Northern line to travel between them. Why? Because the map suggests a gap. It’s a psychological trick. We trust the paper more than our own feet.

The map also makes the West End look enormous and South London look like a barren wasteland. Notice how the River Thames is basically a decorative squiggle? It’s not to scale. Nothing is. The map is a "schematic," which is a fancy way of saying it’s a beautiful lie that helps us get to work on time.

The Secret Layers You Never See

The standard map of the tube stations you see on the platform is just the tip of the iceberg. There are versions of this map that would make your head spin. There’s a "walking distance" map produced by TfL that finally admits how close some stations are. There’s a map showing the number of steps between stations. There’s even a map showing the depth of each station—did you know Hampstead is 58 meters underground? That’s almost twenty stories.

Then there are the "ghost stations."

British Museum. Down Street. Brompton Road. These are names that used to be on the map of the tube stations but were scrubbed out. Down Street was used as a bunker by Winston Churchill during the Blitz. You can still see the dark voids of these platforms as your train rattles past them, if you know where to look. They are the scars of a changing city.

The map has to evolve. Every time a new piece of infrastructure like the Elizabeth Line or the Northern Line Extension arrives, the design team has to perform a kind of visual Tetris. They have to squeeze new lines into an already crowded frame without breaking the "Beck" logic.

✨ Don't miss: The William E. Dever Crib: Chicago’s Strange Lake Michigan "Lighthouse" Explained

The Politics of the Zone

The map isn't just about travel; it’s about money. The concentric circles of the zones determine your rent, your commute cost, and your social status.

When a station gets moved from Zone 3 to Zone 2, house prices in that neighborhood spike. It’s the "Map Effect." The map of the tube stations literally redraws the economic boundaries of the city. Look at the recent shift of Stratford. It was moved to "Zone 2/3" to make it more attractive for commuters and businesses after the Olympics.

It’s an exercise in branding. If you’re on the map, you exist. If you’re not? You’re in the wilderness. This is why there’s always a massive outcry whenever a line is closed or a station is renamed. It’s like being erased from the city’s consciousness.

How to Actually Use the Map Without Getting Fooled

Don't be a slave to the lines. If you want to master London, you have to learn to ignore the map occasionally.

- Check the walking maps. Seriously. TfL publishes a map that shows which stations are within a 10-minute walk of each other. It will save you a fortune in Oyster credit.

- The "Labyrinth" is real. In 2013, to celebrate the 150th anniversary, artist Mark Wallinger installed a unique "Labyrinth" artwork in every single one of the 270 stations. Finding them is a much better way to explore the map than just commuting.

- Look for the "Dagger" symbols. Sometimes you'll see a little symbol next to a station name. This usually means there’s no step-free access or there are specific restricted hours. The map is dense with these tiny warnings.

- Embrace the Overground. People often ignore the orange lines because they look "complicated" on the map of the tube stations, but the Overground is often the fastest way to bypass the congested center.

The map is a tool, not a holy text. It was designed to solve the problem of a 1930s commuter, and while it’s been updated, the core DNA remains a simplification of a very messy, very old city.

The next time you’re staring at that colorful tangle of lines, remember: the shortest distance between two points isn't a straight line on a map. It’s usually the street you’re standing on.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Trip

Before you tap in at the barriers, take a second to look at a "Real Distance" map on your phone. Compare it to the standard schematic. You'll quickly see that the "hubs" like King's Cross or Waterloo are actually sprawling complexes where the walk between lines is longer than the actual train ride.

If you are traveling in Zone 1, try walking one stop. Just one. You'll see more of London in those ten minutes than you will in ten hours of staring at the back of someone's head on the Central Line. Use the map of the tube stations to get to your general neighborhood, then put your phone away and look at the actual buildings. That’s where the real London is hiding.