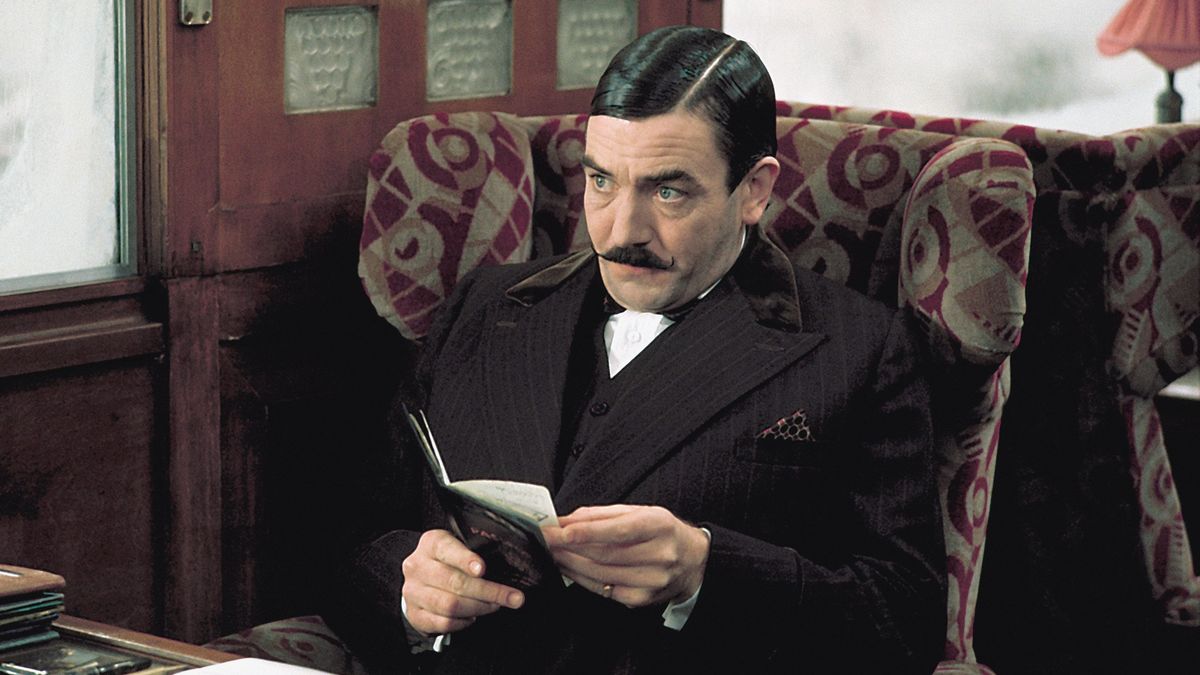

David Suchet lived as Hercule Poirot for over two decades. But something shifted in 2010. When fans sat down to watch the Murder on the Orient Express 2010 episode of Agatha Christie's Poirot, they weren't greeted with the usual cozy mystery tropes or the whimsical, egg-shaped detective they’d grown to love since the late eighties.

It was grim.

The lighting was desaturated, the snow felt claustrophobic, and the moral weight was crushing. Most people think they know this story because of the 1974 film or the flashy Kenneth Branagh version from a few years back. Honestly, though? The 2010 version directed by Philip Martin is a completely different beast. It’s the only adaptation that treats the ending like a genuine spiritual crisis rather than a clever puzzle solved by a man with a funny mustache.

The struggle for Poirot's soul

Most adaptations of this book focus on the "how." How did twelve people manage to stab a man in a locked train compartment? But the Murder on the Orient Express 2010 screenplay, written by Stewart Harcourt, focuses almost entirely on the "why" and the subsequent "now what?"

📖 Related: The Brutal Honesty of I Don’t Wanna Be Me Lyrics: Why Peter Steele’s Self-Loathing Still Hits Hard

Poirot is a devout Catholic. That's a detail from Christie’s books that often gets glossed over in favor of his obsession with symmetry and "the little grey cells." Here, it's front and center. The episode opens in Palestine with Poirot witnessing a soldier commit suicide after being caught in a lie. It’s a brutal, jarring start. It sets the tone for a man who is increasingly weary of a world that refuses to follow his rigid rules of order and justice.

When he boards that train, he isn't looking for a holiday. He’s looking for a way to reconcile his faith with the filth he sees every day. Then he meets Ratchett, played by Toby Jones with a repulsive, oily desperation. Ratchett isn't just a villain here; he's a symbol of pure, unadulterated evil that the law failed to catch.

Why this cast hits differently

You’ve got Jessica Chastain as Mary Debenham. You’ve got Barbara Hershey as Mrs. Hubbard. These aren't just cameos; they are performances rooted in deep, agonizing grief. In the 1974 version, the reveal of the killers feels almost celebratory—a "gotcha" moment where the family gets their revenge.

In the Murder on the Orient Express 2010 version, the reveal is devastating.

When the twelve passengers are lined up in that cold, dim dining car, they don't look like victors. They look like ghosts. They look like people who died years ago when the Armstrong baby was kidnapped and murdered, and they’re just now realizing that killing Ratchett didn't actually bring them back to life. It’s heavy stuff. It’s not "Sunday evening tea" television.

The chemistry between Suchet and the ensemble is tense. You can feel the collective breath being held. Unlike other versions where Poirot seems to enjoy the theatricality of the reveal, here he is visibly disgusted. He’s shouting. He’s angry. He’s holding a rosary and shaking because he realizes that if he lets these people go, he is breaking the law of man and the law of God. If he turns them in, he is destroying twelve lives that have already been shattered once.

The controversial ending people still argue about

If you’ve seen any other version, you know the ending. Poirot presents two solutions. One is a lie (a mysterious intruder did it), and one is the truth (everyone did it). Usually, the train director, M. Bouc, chooses the lie, and Poirot nods along, satisfied that justice—in a poetic sense—has been served.

The Murder on the Orient Express 2010 ending is far more complicated.

Poirot doesn't just "agree" to the lie. He is forced into it by the sheer weight of the tragedy. He delivers the truth with a ferocity that makes the passengers weep. When he finally hands over the evidence and walks away into the snow, he is crying. He is a broken man.

Some fans hated this. They felt it was too "dark" for Poirot. But honestly? It’s probably the most honest depiction of what that situation would actually do to a man of Poirot’s convictions. You can’t just walk away from a mass stabbing feeling "jolly good."

A masterpiece of technical dread

Visually, this isn't the lush, golden-age travelogue you might expect. The train feels small. The corridors are narrow. The sound design is dominated by the screeching of the brakes and the howling wind outside. It’s a horror movie disguised as a whodunnit.

- The Lighting: Deep shadows hide the faces of the passengers, suggesting their dual natures.

- The Pace: It lingers on the silence. There are long stretches where no one speaks, and we just watch the gears turning in Poirot’s head.

- The Music: Christian Henson’s score avoids the sweeping orchestral themes of the past, opting instead for something more somber and dissonant.

It’s worth noting that this was produced during the final seasons of the Poirot series. The creators knew the end was coming for the character, and they were leaning into the darker, more philosophical elements of the later novels. They weren't making content for casual viewers anymore; they were making a definitive statement on the character’s legacy.

What most people get wrong about the 2010 version

A common criticism is that the 2010 adaptation is "too depressing." People say Christie wrote light mysteries. That’s a total misconception. If you actually read the later Christie novels, she was obsessed with the nature of evil and the psychological toll of crime.

The Murder on the Orient Express 2010 film is actually closer to the spirit of Christie’s darker themes than the 1974 movie ever was. It acknowledges that the Armstrong kidnapping was based on the real-life Lindbergh tragedy—a case that horrified the world. It treats the death of a child with the gravity it deserves rather than using it as a convenient plot device.

Also, some viewers think Poirot's outburst at the end is out of character. It’s not. In the book, Poirot is often described as having "eyes that glow green" when he’s angry. He’s a man of passion, not just a thinking machine. Suchet captures that better in this episode than in almost any other in the series' 24-year run.

How to watch it today

If you want to revisit the Murder on the Orient Express 2010 adaptation, it’s usually available on BritBox or Acorn TV, depending on where you live. It’s Season 12, Episode 3 of the Poirot series.

Don't go into it expecting a fun romp. Put away your phone. Turn off the lights. It’s a film that demands your full attention because so much of the story is told in the flickers of Poirot’s eyes and the trembling hands of the suspects.

Actionable insights for the mystery fan

If you’re a fan of the genre, there are a few things you should do to get the most out of this specific version.

📖 Related: Way of the Dragon: Why Bruce Lee’s Colosseum Fight Still Matters

- Read the Lindbergh Case history. Understanding the real-life horror that inspired the Armstrong story makes the desperation of the killers in the 2010 version much more palpable.

- Watch the 1974 and 2017 versions first. Seeing the "standard" ways this story is told makes the 2010 version’s subversions much more impactful. You’ll notice the differences in how the "second solution" is presented immediately.

- Pay attention to the religious iconography. From the rosary beads to the way the dining car is staged like a courtroom or a church, the 2010 film is thick with symbolism about judgment and penance.

- Listen to the silence. Unlike modern blockbusters, this adaptation uses silence as a weapon. Notice when the music stops—it’s usually when a character is about to break.

The Murder on the Orient Express 2010 remains the gold standard for fans who want their mysteries with a side of moral complexity. It’s not just a "whodunnit." It’s a "should we have done it?" And that is a much more interesting question to answer.

To truly appreciate the nuance of this adaptation, compare the final scene of Poirot walking in the snow to the final scene of Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case. You’ll see a direct line of character development that explains exactly why the detective ended up where he did. It is a masterclass in long-form character arcs that few shows have ever matched.