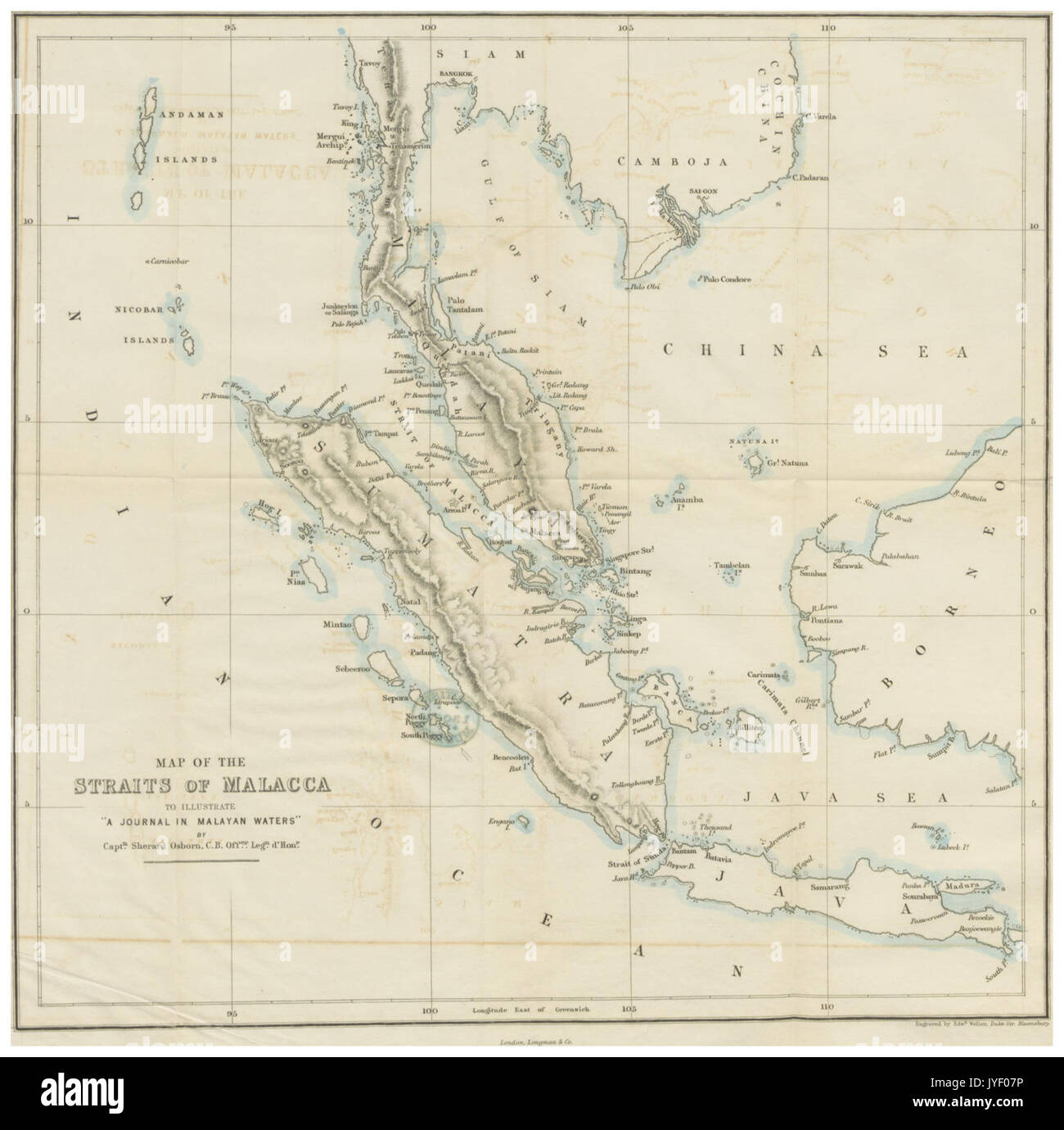

If you look at a Straits of Malacca map, you’ll see a skinny, funnel-shaped stretch of water that looks almost claustrophobic compared to the vastness of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It’s barely 500 miles long. At its narrowest point, the Phillips Channel near Singapore, it’s only 1.7 miles wide. That is tiny. Honestly, it’s terrifyingly small when you realize that nearly a quarter of all global trade squeezed through that gap this morning while you were drinking your coffee.

For decades, we’ve treated this waterway as a given. But looking at the geography today, you start to see why military planners and logistics nerds lose sleep over it. It’s a literal choke point. If something goes wrong here—a shipwreck, a blockade, or even a localized conflict—the global economy doesn't just slow down. It breaks.

📖 Related: How to Become a Seller on Etsy Without Losing Your Mind (or Your Savings)

The Geography of a Global Choke Point

The Straits of Malacca map connects the Andaman Sea to the South China Sea, running between the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian island of Sumatra. It's the shortest sea route between Middle Eastern oil suppliers and the massive markets in East Asia like China, Japan, and South Korea.

Think about the sheer volume.

About 100,000 vessels pass through every year. We are talking about everything from massive ULCCs (Ultra Large Crude Carriers) to tiny regional fishing boats that constantly weave in and out of the shipping lanes. The water isn't even that deep. In some spots, it’s only about 25 meters deep. For a ship carrying two million barrels of oil, that is a tight squeeze. Sailors call it "The Ditch" for a reason.

Why Singapore Wins Every Time

Look at the bottom right of any Straits of Malacca map and you’ll see Singapore sitting there like a toll booth collector. It is the ultimate real estate play. Because the strait narrows so significantly right at Singapore's doorstep, every ship is basically forced to pass within sight of the city-state.

This isn't just about geography; it's about infrastructure. Singapore has turned its spot on the map into the world's premier transshipment hub. They aren't just watching ships go by; they are refueling them, repairing them, and moving containers from one ship to another. Without that specific bend in the map, Singapore would just be another island. Instead, it’s the heartbeat of global logistics.

The Malacca Dilemma and China’s Energy Panic

Former Chinese President Hu Jintao coined a phrase that still dominates Beijing’s foreign policy: the "Malacca Dilemma."

China is the world's largest oil importer. Roughly 80% of those imports come through this one tiny stretch of water. If a rival power—say, the U.S. Navy—decided to park a few destroyers at the mouth of the strait, they could effectively turn off the lights in Shanghai within weeks. It's a massive strategic vulnerability.

🔗 Read more: Pan African Food Distributors: Why the Supply Chain is Finally Changing

Because of this, you’re seeing China spend billions on the "Belt and Road Initiative." They are trying to draw a new Straits of Malacca map that doesn't actually include the straits. They’re building pipelines through Myanmar and railroads through Central Asia. They are desperate for a "Plan B" because relying on a 1.7-mile-wide gap for your entire national survival is, frankly, a bad business plan.

Pirates, Ghosts, and Modern Security

People think piracy is something from the 1700s with wooden legs and parrots. It’s not. It’s very much a 2026 problem.

The Straits of Malacca map is dotted with thousands of tiny islands, mangrove swamps, and hidden river mouths. For a pirate, this is paradise. You can strike a slow-moving tanker and disappear into a maze of Indonesian islands before the local coast guard even gets the radio call.

While the Strait of Aden (near Somalia) gets all the headlines, Malacca has historically been more active. Most of the "piracy" here is actually low-level robbery—people boarding a ship to steal engine parts or the crew’s cash. But the threat of a "phantom ship"—where pirates hijack a vessel, paint over its name, and sail it to a different port to sell the cargo—is a very real nightmare for insurance companies at Lloyd's of London.

The Environmental Time Bomb

If a major collision happened in the narrowest part of the strait, the environmental disaster would be unprecedented. The current moves in such a way that an oil spill would coat the coastlines of three different countries almost simultaneously.

👉 See also: How Many Billionaires in World: What the New 2026 Data Actually Shows

- Malaysia: Fishing industries would collapse overnight.

- Indonesia: The delicate ecosystems of Sumatra would be decimated.

- Singapore: Desalination plants, which provide the city's drinking water, could be fouled.

The complexity of cleaning up a spill in such a high-traffic area is why the Malacca Straits Council exists. They manage the TSS (Traffic Separation Scheme), which is basically a highway system for ships to keep them from bumping into each other. It’s a delicate dance performed by thousand-foot-long lead dancers.

Navigating the Future of the Map

Is there an alternative? Sort of.

The Kra Isthmus in Thailand has been a "maybe" project for centuries. The idea is to dig a canal across Thailand so ships can bypass the Straits of Malacca map entirely. It would save about 1,200 kilometers of travel. But it would cost upwards of $30 billion and create a host of political headaches for Thailand. For now, it remains a pipe dream.

Then there’s the Sunda Strait and the Lombok Strait. They are deeper and wider, but they add days to a journey. In the world of "Just-In-Time" manufacturing, an extra three days of fuel and labor costs is an eternity.

Actionable Insights for the Global Observer

Understanding the Straits of Malacca map isn't just for history buffs or sea captains. It’s a lesson in how physical geography still dictates our digital, high-speed world. If you’re looking at this from a business or strategic perspective, here is what you need to track:

- Monitor Port Congestion in Singapore: When Singapore backs up, it’s a leading indicator of global supply chain friction. This often happens months before you see price hikes on your favorite electronics.

- Watch the "Dry Canal" Projects: Keep an eye on the development of the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) in Malaysia. It’s a land-bridge designed to move cargo from one side of the peninsula to the other, bypassing the southernmost tip of the straits.

- Insurance Risk Premiums: If you see "War Risk" or "Kidnap and Ransom" insurance rates spike for vessels in the region, expect shipping costs to rise globally. These costs are always passed down to the consumer.

- Satellite AIS Data: You can actually watch this in real-time. Use tools like MarineTraffic to see the density of ships on a live Straits of Malacca map. The sheer "clump" of icons around the Phillips Channel will tell you everything you need to know about why this area is so high-stakes.

The world might be more connected than ever through fiber-optic cables, but those cables are often laid along the seabed of these very straits. We are still a world of physical goods moved by physical ships through very narrow physical gaps. Geography is destiny, and right now, the destiny of the global economy is squeezed through the Straits of Malacca.