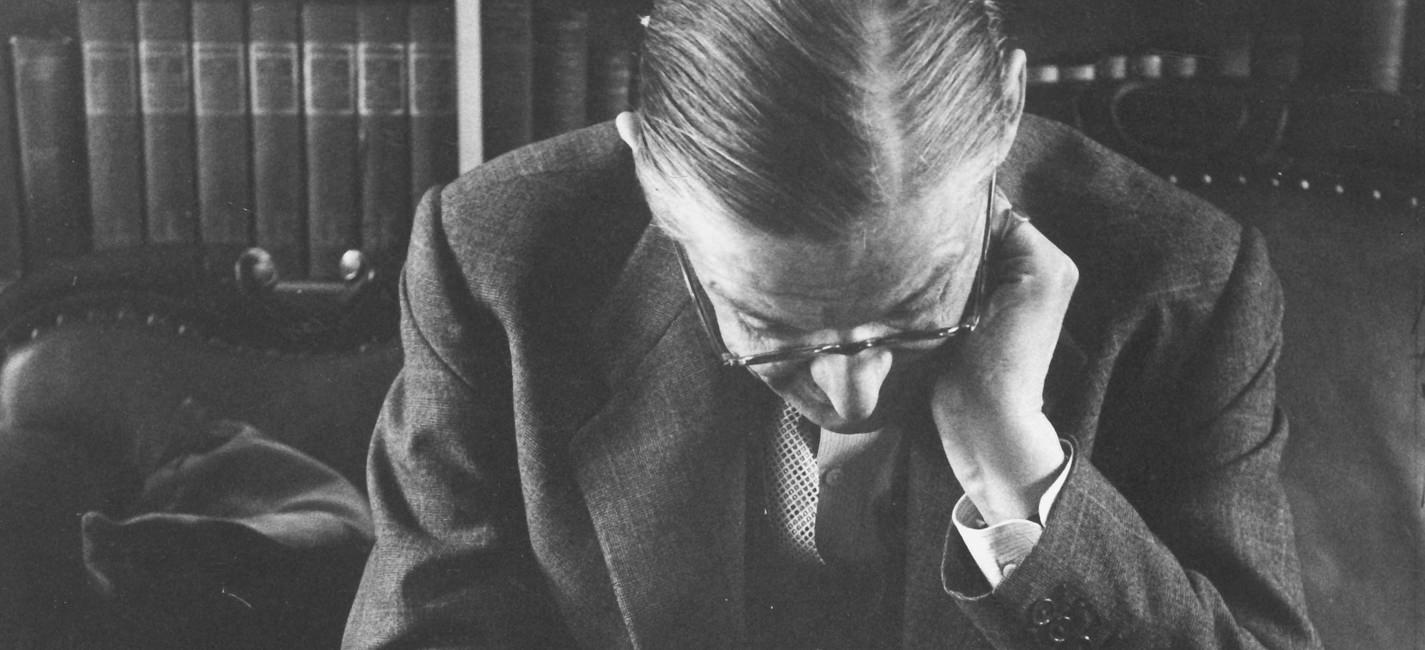

T.S. Eliot was exhausted. By 1930, the man who had basically dismantled the old world of poetry with The Waste Land was looking for something that didn't feel like falling apart. He found it in the Anglican Church, but the transition wasn't exactly smooth or easy. When you sit down with the T S Eliot Ash Wednesday text, you aren't just reading a poem; you’re looking at a guy trying to learn how to pray while his brain keeps trying to pull him back into the cynical, intellectual void he spent a decade mapping out. It’s messy. It’s gorgeous. Honestly, it’s one of the most honest depictions of a mid-life spiritual pivot ever put to paper.

The Struggle Inside the T S Eliot Ash Wednesday Text

Most people come to this poem expecting a clean, religious anthem. They think, "Oh, Eliot converted, so now he’s going to be straightforward and holy." Nope. Not even close. The poem opens with that famous, stuttering line: "Because I do not hope to turn again." It’s repetitive. It feels like someone pacing in a small room. Eliot is dealing with "the vanished power of the usual reign." He’s basically saying he’s done with the old ways of seeking power or worldly success, but he hasn't quite figured out what comes next.

If you look at the T S Eliot Ash Wednesday text closely, you’ll notice it’s divided into six distinct parts. But don't expect a linear progression. It’s more like a spiral. He goes from despair to a weird, surreal vision of three white leopards under a juniper tree, and eventually to a point of quiet, almost silent, surrender. It’s "the time of tension between dying and birth." That’s the sweet spot of the whole work. He’s stuck in the middle.

Why the Leopards Matter

Wait, leopards? Yeah. In Part II, Eliot gets weird. He describes three white leopards who have eaten his "legs my heart my liver and that which had been contained in the hollow round of my skull." It sounds like a horror movie, but it’s actually a riff on the visionary style of Dante. He’s talking about the total dismantling of the ego. To get to the "Lady" (often seen as a symbol of the Virgin Mary or divine wisdom), the old Eliot—the banker, the critic, the depressed husband—has to be consumed.

📖 Related: Hello Love Again Torrent: What Most People Get Wrong

The Language of "Turning"

The word "turn" shows up constantly. It’s a literal translation of metanoia, which is the Greek word for repentance. But for Eliot, it’s also a physical sensation. You can feel the gears grinding.

- He doesn't hope to turn.

- He hopes to "construct something upon which to rejoice."

- He struggles with the "devil of the stairs."

That third part is crucial. The "stair" represents the spiritual climb. As he goes up, he looks back down the banister and sees the "slotted window bellied like the fig's fruit." It’s a sensory distraction. It’s the world saying, "Hey, look how pretty I am, don't go up those dusty stairs." We've all felt that. You try to commit to something—a diet, a project, a relationship—and the old, easy distractions start looking better than they ever did before. Eliot isn't writing from a pedestal here; he’s writing from the trenches of his own indecision.

The Influence of Dante and the Liturgy

You can't talk about the T S Eliot Ash Wednesday text without mentioning the heavy lifting done by outside sources. Eliot was a magpie. He stole from the best.

- The Book of Common Prayer: You’ll see "Lord, I am not worthy" and "And after this our exile."

- Dante Alighieri: The structure of the climb is pure Purgatorio.

- St. John of the Cross: The "dark night of the soul" vibes are everywhere.

The poem is a collage. But unlike The Waste Land, which felt like a pile of broken glass, Ash Wednesday feels like a mosaic being slowly glued back together. It’s quieter. There are fewer footnotes required to understand the feeling, even if the specific references are still pretty dense.

Is It Actually "Religious" Poetry?

Yes and no. It’s religious in the way that a fever dream about God is religious. It’s not a hymn. You won’t hear this sung in many Sunday morning services because it’s too uncomfortable. It deals with the "place of solitary hearse" and the "last desert between the last blue rocks."

Some critics at the time, like Edmund Wilson, were kind of annoyed by it. They felt like Eliot was retreating from the modern world into an old, dusty attic of incense and Latin. But they missed the point. Eliot wasn't retreating; he was trying to find a language that could handle the fact that being a modern person is exhausting. He needed a structure. The T S Eliot Ash Wednesday text provided that scaffold. It gave him a way to say "I'm lost" without it being the end of the story.

The "Lady" and the Rose

In the middle sections, there’s this recurring image of a Lady and a Rose Garden. If you’ve read Burnt Norton, you know Eliot has a thing for rose gardens. They represent the "might have been"—the moments of pure joy or clarity that we usually miss. In Ash Wednesday, the Lady is the mediator. She’s silent. She’s bent over. She’s the personification of the peace he’s chasing.

- The Garden: A place of restoration.

- The Desert: The place where you actually have to do the work.

- The Silence: The goal.

How to Read the T S Eliot Ash Wednesday Text Today

If you’re trying to tackle this poem, don't try to "solve" it like a crossword puzzle. That’s where most students go wrong. They get hung up on the "yew trees" or the "veiled sister" and forget to feel the rhythm.

Read it out loud. Seriously.

The poem relies on incantation. The repetitions—"May the judgment not be too heavy upon us," "Teach us to care and not to care"—work like a heartbeat. It’s meant to wash over you. If you don't get a specific reference to a 17th-century sermon, it doesn't matter. You get the feeling of a man trying to hold his breath underwater.

💡 You might also like: Clean Bandit Rather Be Official Video: Why It Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Common Misconceptions

A lot of people think this poem is about being sad because it's named after a day of penance. But Ash Wednesday is also about the possibility of change. It’s the start of something.

Another big mistake? Thinking Eliot had it all figured out by the time he wrote the final stanza. He didn't. The ending—"Our peace in His will"—is a quote from Dante, but Eliot frames it as a plea, not a settled fact. He’s still "wavering." He’s still "between the yew trees." He’s human.

Actionable Takeaways for Approaching the Text

To truly grasp what’s happening in the T S Eliot Ash Wednesday text, you should move beyond the digital screen and engage with the material context.

- Listen to Eliot's own recording. There are archival recordings of Eliot reading this poem. His voice is dry, rhythmic, and slightly mournful. It changes the way you see the line breaks.

- Compare it to "The Hollow Men." Read them back-to-back. The Hollow Men is the "death" that Ash Wednesday is trying to wake up from. It provides the necessary contrast.

- Ignore the footnotes on the first pass. Just read. Let the "white leopards" and the "jewelled unicorns" be weird and vivid. The academic stuff can wait for the second or third reading.

- Trace the "Turning." Mark every time the poem mentions turning, spinning, or stairs. You’ll see the physical architecture of the poem emerging from the fog.

The real power of the T S Eliot Ash Wednesday text isn't in its theology. It’s in the way it captures that specific, awkward moment when you decide to change your life and realize you have no idea how to actually do it. It’s the poem for the "in-between" times.

Ultimately, Eliot shows us that the "turning" isn't a one-time event. It’s a constant, repetitive, and often frustrating process of trying to find "the still point of the turning world." Whether you're religious or not, there's something deeply relatable about a person trying to find a bit of quiet in a world that won't stop making noise.