Love is a weird thing. Or at least, the idea of love that Roger Shackleforth has is pretty warped. If you’ve ever sat through the 1960 episode of The Twilight Zone The Chaser, you know exactly what I’m talking about. It’s one of those chapters of Rod Serling’s anthology that starts off feeling like a lighthearted, whimsical rom-com but ends up leaving a metallic, bitter taste in your mouth. Honestly, it’s one of the most cynical looks at human relationships ever put to film, and the scary part isn't a monster or a nuke—it’s the suffocating reality of getting exactly what you asked for.

Roger is a loser. Let's just say it. He’s obsessed with Leila, a woman who clearly wants nothing to do with him. He calls her constantly. He hovers. He’s the physical embodiment of a "nice guy" who can't take a hint. When he finally seeks out an old chemist named A. Gaston to buy a love potion, he thinks he’s solving his problems. But the episode isn't really about romance. It's about the erasure of consent and the horrifying boredom of a forced reality.

The Economics of Obsession in The Chaser

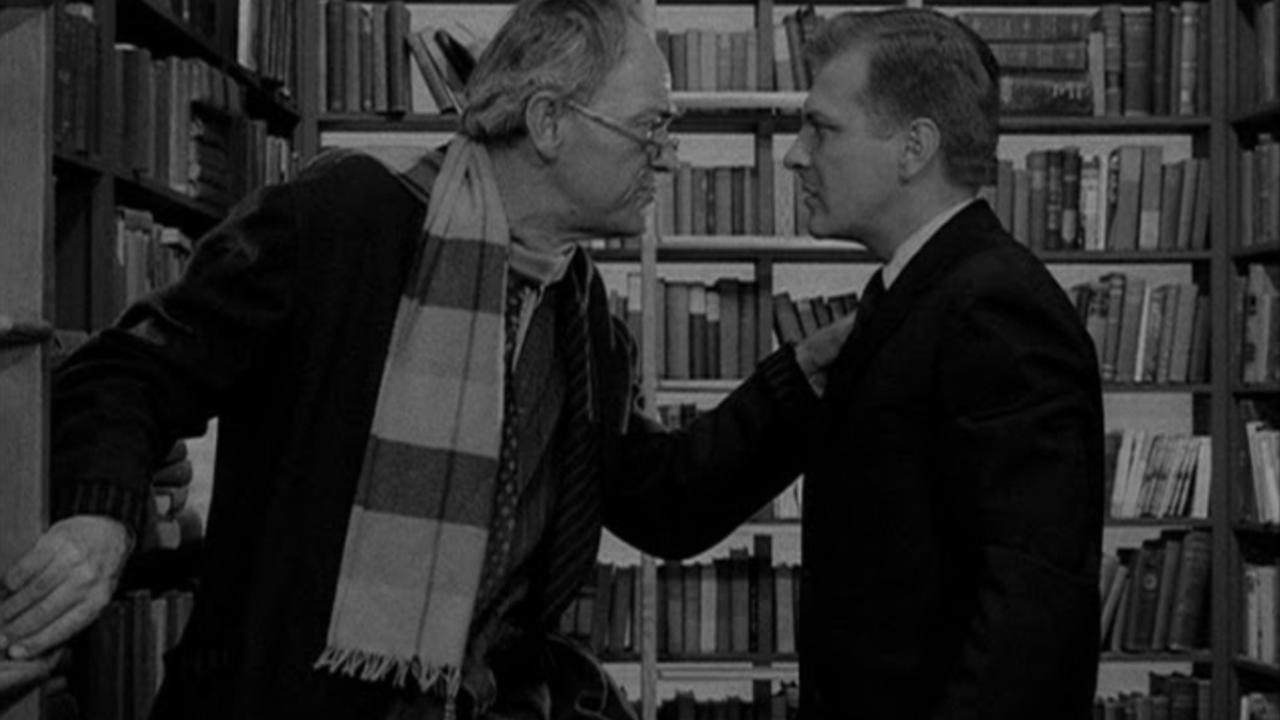

John Hoyt plays A. Gaston with this perfect, weary sophistication. He lives in a cramped apartment filled with books and dust, looking like a man who has seen every human folly at least a dozen times. He sells Roger a love potion for a mere one dollar. One single buck. That’s the first red flag. In the world of Serling, if the solution to your life's greatest problem costs less than a sandwich, you’re in deep trouble.

Gaston knows the trajectory. He’s a businessman who understands the long game. He tells Roger about another concoction—the "glove cleaner." It’s a specialized poison. It's odorless, tasteless, and completely undetectable. It also costs five thousand dollars. Why the price gap? Because Gaston knows that once Roger uses the one-dollar love potion, he’ll eventually be willing to pay anything to undo the damage. It’s a brilliant, dark bit of foreshadowing that sets the stakes for the entire twenty-five minutes.

When Adoration Becomes an Absolute Nightmare

The transition in Leila’s character is jarring. Patricia Barry plays both sides of the coin brilliantly. Before the potion, she’s aloof, slightly annoyed, and fiercely independent. After Roger slips the "Chaser" into her glass, she becomes a living doll. She doesn't just love him; she worships him. She breathes for him. She lives to serve his every whim.

It sounds like a dream for a guy like Roger, right? Wrong.

The horror of The Twilight Zone The Chaser kicks in during the middle act. We see a montage of their married life. Leila is constantly draped over him. She’s over-attentive. She’s repetitive. She has no opinions, no fire, and no soul of her own anymore. She is a mirror reflecting Roger's ego back at him, and he quickly realizes that he didn't actually want love. He wanted a trophy. But a trophy doesn't talk back, and a trophy doesn't demand your constant attention in return. Roger is now a prisoner of the very devotion he manufactured.

Serling’s writing here is sharp. He’s mocking the "happily ever after" trope by showing the claustrophobia of a partner who never disagrees. If you’ve ever been in a relationship where one person does all the emotional heavy lifting, this episode hits way too close to home. It’s the ultimate "be careful what you wish for" scenario because the punishment isn't death—it's a lifetime of suffocating sweetness.

The Script vs. The Source Material

Interestingly, this wasn't an original Serling idea. It was based on a short story by John Collier. If you read the original text, it's even more clinical. Collier was a master of the "macabre whimsey" style, and the TV adaptation stays remarkably true to that tone. However, the show adds that specific 1950s/60s suburban veneer that makes the ending feel even more trapped.

Robert Stevens, the director, uses close-ups to make the apartment feel smaller as the episode progresses. By the time Roger is contemplating the "glove cleaner," the walls feel like they’re closing in. It’s a masterclass in using set design to reflect a character's mental state. You feel Roger’s desperation. You almost—almost—feel bad for him, until you remember that he basically chemically lobotomized a woman because she didn't like him.

Why the Ending Still Sparks Debate

The final scene is where the real gut punch happens. Roger invites Gaston over, intending to buy the five-thousand-dollar poison. He’s done. He can't take another "I love you" or another moment of Leila’s undivided attention. But then, Leila reveals she’s pregnant.

📖 Related: Why the Hot or Not Show Still Haunts Our Digital Culture

Roger folds. He can’t do it. He breaks the vial of poison. He accepts his fate.

Gaston leaves, puffing on a cigar, knowing he’ll probably see Roger again, or someone just like him. The tragedy isn't just that Roger is stuck; it’s that the cycle of obsession and regret is a profitable industry for men like Gaston. The "Chaser" isn't just the potion; it's the aftermath. It's the thing you drink to wash down the first mistake, only to realize the taste never really goes away.

Many viewers interpret the ending as Roger finally growing up, but that’s a pretty generous read. It’s more likely that Roger is just a coward who is moving from one form of entrapment to another. He’s trapped by the potion, then by the child, and ultimately by his own inability to exist without some form of external validation, even if it's fake.

The Technical Brilliance of Hoyt and Barry

We have to talk about the acting. John Hoyt’s performance as the chemist is foundational for the "mysterious shopkeeper" trope we see in later shows like The X-Files or Tales from the Crypt. He doesn't play it like a villain. He plays it like a pharmacist who’s tired of explaining the side effects to people who won't listen.

Patricia Barry’s shift is equally impressive. The way her eyes go slightly vacant once the potion takes hold is chilling. It’s a subtle bit of physical acting that transforms a romantic comedy setup into a psychological thriller. She becomes a ghost haunting her own life.

Practical Insights for Twilight Zone Fans

If you're revisiting this episode or watching it for the first time, keep an eye on these specific details to get the most out of the experience:

- Watch the background items in Gaston’s shop. The set dressers packed it with subtle hints of previous "customers" and their failed lives.

- Pay attention to the lighting shifts. The episode starts in high-key, bright lighting and gradually moves into deeper shadows as Roger's regret grows.

- Contrast the dialogue. Count how many times Leila says "Roger" in the second half. It’s designed to be rhythmic and irritating, mimicking the sound of a ticking clock.

- Research John Collier. If you like the vibe of this episode, his short story collection Fancies and Goodnights is essential reading for fans of dark irony.

The Twilight Zone The Chaser remains a standout because it avoids the typical sci-fi trappings of the era. There are no aliens or time machines. There is just a man, a bottle, and the horrifying reality of a forced "perfect" life. It serves as a permanent reminder that the most dangerous things in the world aren't always found in outer space; sometimes, they're found in a one-dollar vial and a heart that doesn't know when to quit.

To truly appreciate the nuance of this era of television, look into the production history of Season 1. This was an era where writers like Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont were pushing the boundaries of what "horror" could be, often finding it in the mundane aspects of domestic life. The Chaser is the crown jewel of that specific, uncomfortable subgenre.

Next Steps for Deeper Exploration

To get a full handle on the themes presented here, you should compare this episode to "A Nice Place to Visit" (Season 1, Episode 28). Both episodes deal with the idea that getting exactly what you want, without effort or merit, is the literal definition of hell. While "The Chaser" focuses on romantic obsession, "A Nice Place to Visit" focuses on greed and ego. Watching them back-to-back provides a comprehensive look at Serling’s philosophy on human desire. You might also want to track down the original John Collier story to see how the ending was slightly softened for 1960s television standards—the prose version is arguably much darker. Regardless of how you view it, the lesson is clear: some prices are too high, even when they only cost a dollar.