Honestly, most people think of the Valley of the Kings as just a bunch of dusty holes in the ground where some guys in pith helmets found gold a hundred years ago. It’s a bit more than that. It’s basically a massive, subterranean labyrinth that served as the final resting place for the heavy hitters of Egypt’s New Kingdom. We’re talking about the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties. This wasn't some public cemetery; it was a high-security, top-secret storage unit for the souls of people like Thutmose III and Ramses the Great.

For about 500 years, from roughly 1539 to 1075 BC, the Egyptians stopped building massive pyramids. They realized that a giant "look at me" triangle on the horizon was basically a neon sign for grave robbers. Instead, they went underground. They chose a desolate wadi on the west bank of the Nile, right across from modern-day Luxor, tucked beneath a peak called al-Qurn. Fun fact: al-Qurn actually looks like a natural pyramid from the valley floor. It’s almost like they found a pre-built monument and decided to dig underneath it.

The Valley of the Kings: What most people get wrong about the "Curse"

You’ve heard about the curse. Everyone has. But if you actually walk into KV62—that’s Tutankhamun’s tomb—you aren't going to see a warning label about death on swift wings. That was mostly a media invention by journalists who were annoyed that Lord Carnarvon gave the Times of London exclusive rights to the dig. The reality is much more interesting. The Egyptians didn't want to kill you with magic; they wanted to confuse you with architecture.

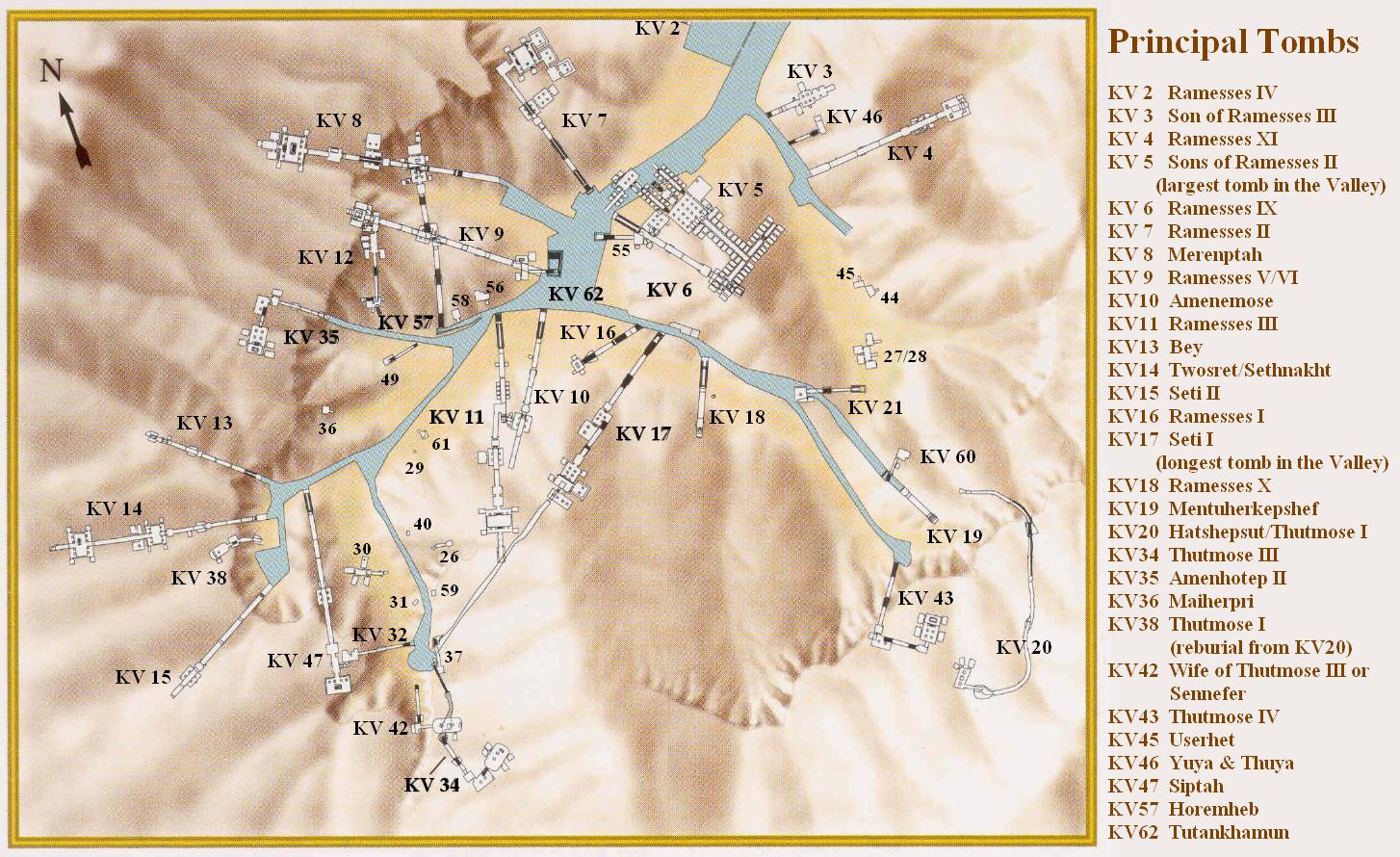

Take KV5. For years, archeologists thought it was just a small, unimportant pit. Then, in the late 80s and early 90s, Kent Weeks and the Theban Mapping Project decided to take a second look. They realized it wasn’t a small tomb. It was a massive, sprawling complex with over 120 rooms, built for the sons of Ramses II. It’s still being excavated today. We’re still finding rooms. It’s the largest tomb in the valley, and we walked right past it for a century because it was filled with debris and looked like nothing.

Why did they pick this specific spot?

It wasn't just the pyramid-shaped hill. Geologically, the Valley of the Kings is a mix of limestone and shale. The limestone is great for carving detailed reliefs, but the shale is a nightmare. It expands when it gets wet. When rare flash floods hit the valley, the water seeps in, the shale expands, and the limestone cracks. This is why some tombs look pristine while others look like a cave-in happened yesterday.

Security was the other big driver. The valley has a single, narrow entrance. In the New Kingdom, a group of elite guards called the "Medjay" patrolled the ridges. They weren't just hanging out; they were actively hunting for anyone trying to sneak a peek at where the gold was hidden. Even with all that, almost every single tomb was looted in antiquity. Sometimes it was even an "inside job" by later pharaohs who needed the gold to fund their own wars or monuments. History is messy like that.

The engineering madness of the 18th Dynasty

In the beginning, the tombs were "bent." If you look at the layout of Thutmose III’s tomb (KV34), the corridor takes a sharp 90-degree turn. Scholars used to think this was to fool robbers or symbolize the path of the sun through the underworld. Whatever the reason, it makes for a claustrophobic, dizzying experience.

The walls are covered in the Amduat. This is basically a guidebook for the afterlife. It describes the twelve hours of the night, where the sun god Ra travels through the underworld in a boat. He has to fight a giant chaos serpent named Apophis every single night. If he loses, the sun doesn't rise. No pressure. The art isn't "pretty" in the traditional sense; it’s functional. It’s like a set of instructions for the soul to navigate a dangerous video game level.

🔗 Read more: Why Nashville Convention & Visitors Corp Still Runs Music City

The shift to straight-axis designs

By the time you get to the 19th Dynasty, like the tomb of Seti I (KV17), the "bent" design is gone. They went for long, straight corridors that plunge deep into the rock. Seti I's tomb is arguably the most beautiful thing in the valley. The colors are so vivid you'd swear they were painted last week, not 3,300 years ago.

- The ceilings are painted deep blue with golden stars.

- The reliefs are raised, meaning they carved away the background rock to leave the figures standing out.

- The burial chamber has an astronomical ceiling that tracks the constellations.

It’s about 137 meters long. That’s a lot of rock to move with hand tools. They used copper chisels and wooden mallets. They didn't have flashlights; they used oil lamps with linen wicks. To keep the smoke from ruining the art, they likely added salt to the oil. It’s the little details like that which make you realize how sophisticated these "ancient" people really were.

The Tutankhamun outlier

Let's be real: Tutankhamun was a minor king. He died young, he didn't do much, and his tomb is tiny. It was likely a repurposed noble's tomb because he died so suddenly they didn't have his "real" home ready. The only reason we care about him is that his tomb was covered by the debris of a later tomb (KV9, Ramses VI), which hid it from robbers.

When Howard Carter found it in 1922, he didn't just find gold. He found 5,000 items crammed into a space the size of a two-car garage. There were chariots, couches, jars of honey that were still technically edible (though I wouldn't try it), and even a lock of his grandmother's hair. It gives us a baseline. If a minor king had this much stuff, can you imagine what was inside the tomb of a powerhouse like Amenhotep III? It’s enough to make a modern historian cry.

The workers lived in a "bubble"

About a twenty-minute walk over the ridge is a place called Deir el-Medina. This is where the guys who actually built the tombs lived. They were literate, they were well-fed, and they were occasionally grumpy. We know this because they left thousands of "ostraka"—shards of limestone used as scrap paper.

We have their grocery lists. We have their doctor's notes (some missed work because of "brewing beer" or "being bitten by a scorpion"). We even have records of the world’s first recorded labor strike. Around 1159 BC, the grain shipments were late, and the workers just put down their tools and walked off the job. They sat in front of the mortuary temples and refused to move until they got paid. Human nature hasn't changed a bit in three millennia.

Modern threats and why you should care

The Valley of the Kings is literally being breathed to death. Every person who enters a tomb exhales moisture. That moisture carries salt into the walls. The salt crystallizes and pops the paint right off the limestone.

The Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities has started rotating which tombs are open to the public to let them "rest." They've also installed high-tech ventilation systems and glass barriers. In some cases, like the tomb of Seti I or Nefertari (in the nearby Valley of the Queens), the ticket price is kept high specifically to limit the number of feet on the ground. It’s a delicate balance between showing the world this history and making sure the history actually survives the next fifty years.

What to actually look for when you go

Don't just stare at the gold leaf. Look at the "grid lines." In some unfinished tombs, you can still see the red charcoal lines the master artists drew to keep the proportions correct. You can see the black corrections made by the head artist when a student messed up a hand or a foot. It makes the whole thing feel human. It’s not just a monument; it’s a construction site that got frozen in time.

Wait, what about the "hidden rooms" in Tut's tomb?

A few years ago, there was a huge buzz about radar scans potentially showing hidden chambers behind the walls of KV62. Some people thought Nefertiti might be back there. Honestly? Subsequent, more advanced scans by the National Geographic Society and others have pretty much debunked it. It was likely just natural voids in the rock. It sucks, but that’s science. Sometimes the answer is just "it's a wall."

How to visit without being "that" tourist

If you're planning a trip, go early. I mean 6:00 AM early. The heat in the valley by noon is brutal—regularly hitting 110°F (43°C) or more. The sun bounces off the white limestone and fries you from all angles.

💡 You might also like: Hard Rock South Lake Tahoe CA: Why This Hotel is Actually a Golden Nugget Now

- Get the extra tickets. Your general entry gets you into three tombs. You usually have to pay extra for the "big ones" like Tutankhamun, Seti I, or Ramses VI. If you’re only going to do one extra, make it Seti I or Ramses VI. The colors in Ramses VI are hallucinogenic.

- Look up, not just left and right. The ceilings are often where the most complex theological stuff is happening.

- Respect the "no photos" signs. Even if you see people doing it, the flash ruins the pigment. Just buy the professional prints or a book in the gift shop.

The Valley of the Kings isn't a museum; it’s a giant, open-air laboratory. Every year, new technology—like Muon tomography—allows us to "see" through the rock without digging. We’re finding anomalies and voids all the time. The valley still has secrets, and honestly, we’ve probably only found about 60% of what’s actually buried there.

Practical next steps for your research

If you're hooked on this and want to go deeper than a basic travel blog, check out the Theban Mapping Project website. It’s the gold standard for actual data on the valley. You can see 3D models of the tombs and read the actual excavation reports.

If you're looking for a book that isn't dry as dust, find The Complete Valley of the Kings by Nicholas Reeves and Richard H. Wilkinson. It’s the bible for this stuff. Also, if you’re actually traveling, hire a private licensed guide through a reputable agency rather than just picking someone up at the gate. A good Egyptologist will point out the "mistakes" in the carvings that you’d never notice on your own, and that’s where the real stories are.

Stop thinking of it as a graveyard and start thinking of it as a massive, high-stakes time capsule. Everything in those tombs was put there with the absolute conviction that it would be needed in the next life. Whether you believe in the afterlife or not, the sheer effort these people put into "forever" is something you have to see to believe.