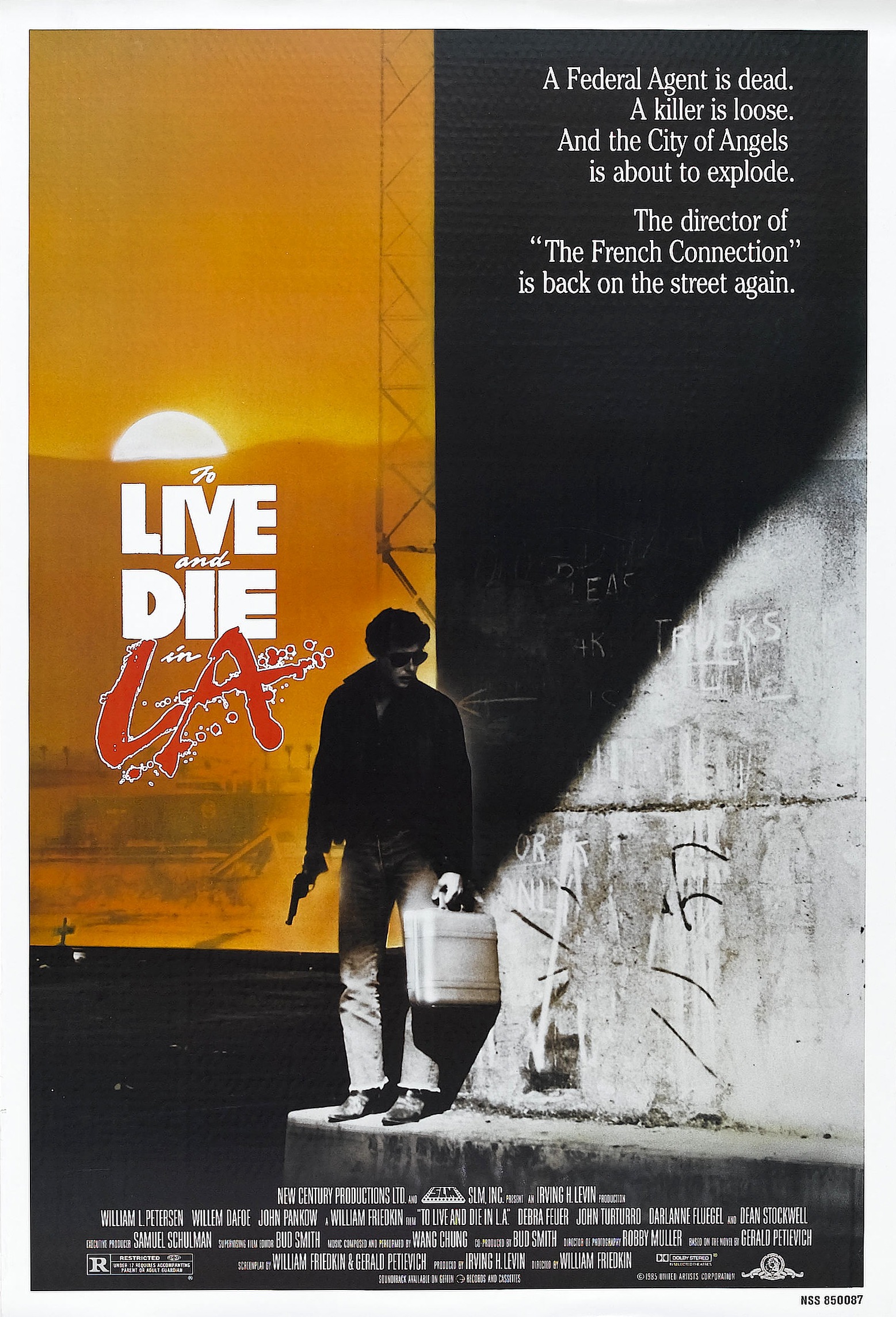

William Friedkin was angry. You can feel it in every frame of To Live and Die in L.A. 1985. While other directors were busy making the eighties look like a neon-soaked MTV playground with synth-pop soundtracks and heroic cops, Friedkin decided to drag the decade through the mud. It’s a movie that smells like exhaust fumes and burnt currency. Honestly, if you watch it today, it feels more modern than most of the polished garbage hitting streaming services right now. It doesn't care if you like the protagonist. It doesn't care about a happy ending.

It just moves.

The plot is deceptively simple, almost a trope if it weren't so cynical. Richard Chance, played by a wiry and reckless William Petersen, is a Secret Service agent. He’s a "cowboy." When his veteran partner gets murdered by a master counterfeiter named Rick Masters—Willem Dafoe at his most chillingly ethereal—Chance goes off the rails. He doesn't just want justice. He wants blood. To get it, he breaks every law he’s sworn to uphold. He steals. He kidnaps. He endangers everyone around him. It’s a descent into moral bankruptcy that makes Miami Vice look like a Saturday morning cartoon.

The Counterfeit Reality of Friedkin’s Vision

Most people talk about the car chase. We’ll get to that. But the real heart of To Live and Die in L.A. 1985 is the process. Friedkin was obsessed with how things actually worked. He hired real counterfeiters as consultants. The scenes where Willem Dafoe’s character prints money? Those aren't just movie magic. They used the actual techniques of the trade. In fact, the production was so good at it that they accidentally printed millions of dollars in "funny money" that was high-quality enough to actually circulate. The Secret Service—the real one—was not amused. They ended up seizing a significant amount of the prop currency.

✨ Don't miss: Game of Thrones Season 6 Actors: What Most People Get Wrong

That authenticity bleeds into the performances. This was Willem Dafoe's breakout. Before he was a Green Goblin or a saint, he was Rick Masters, a man who burned his own paintings because they were "too perfect." He treats counterfeiting like high art. Opposite him, Petersen plays Chance as a man with a death wish. There is a specific kind of eighties machismo that Petersen captures—not the muscular invincibility of Schwarzenegger, but the twitchy, adrenaline-fueled desperation of a guy who has jumped off too many bridges.

The film's look is iconic yet filthy. Robby Müller, the cinematographer who worked with Wim Wenders, shot the hell out of the Los Angeles industrial underbelly. Forget the palm trees of Beverly Hills. This is the L.A. of San Pedro, the concrete riverbeds, and the smog-choked horizon. It looks orange and bruised.

That Car Chase and the Geometry of Chaos

You can't discuss this film without the wrong-way freeway chase. It’s legendary. Friedkin already had The French Connection under his belt, so the pressure was on to outdo himself. He succeeded by making the stakes feel personal and the physics feel terrifying.

It wasn't just about speed. It was about the psychological breakdown of the characters involved. When Chance drives against traffic on the Terminal Island Freeway, it isn't a cool stunt. It’s a sign that he’s lost his mind. The filming took six weeks to coordinate. They used real stunt drivers and jammed them into actual traffic patterns (under controlled conditions, mostly). The result is a sequence that feels claustrophobic despite being on a massive highway. You feel every near-miss. Your hands get sweaty.

A Soundtrack That Defies the Era

Then there's Wang Chung. Usually, when people hear that name, they think of "Everybody Have Fun Tonight." But their work on the To Live and Die in L.A. 1985 soundtrack is a masterpiece of moody, percussive electronic music. It’s driving. It’s anxious.

Friedkin reportedly told the band he didn't want "songs." He wanted a texture. The title track is great, sure, but the instrumental cues are what hold the film together. They provide a rhythmic pulse that mirrors the printing presses and the heartbeat of a man running out of time. It’s one of those rare instances where the music is so inextricably linked to the visuals that you can't imagine the movie without those specific synthesizer swells.

✨ Don't miss: Tamayo from Demon Slayer: The Woman Who Actually Beat Muzan

The Ending That Still Shocks

Without spoiling the specifics for the three people who haven't seen it, the climax of the film is a middle finger to Hollywood conventions. In 1985, audiences expected the hero to win. They expected a quip and a sunset. Friedkin gives them a cold shower.

The studio hated it. They wanted a different ending. Petersen and Friedkin fought for the cynical version, and thank God they did. It cements the movie's theme: in a world of fakes, the only thing real is the dirt. The line between the cop and the criminal isn't just thin; it’s non-existent. Chance and Masters are two sides of the same counterfeit coin. One makes fake money; the other provides a fake sense of security. Both are predators.

Why It Matters Forty Years Later

We live in an era of "prestige" gritty TV and dark reboots. But most of them feel calculated. To Live and Die in L.A. 1985 feels dangerous. It’s a film made by people who weren't afraid to be ugly.

There are no heroes here. Even the "good" characters are compromised. Vukovich, Chance’s new partner played by John Pankow, starts as the moral center and ends up being consumed by Chance’s madness. It’s a bleak look at how corruption is contagious. If you're looking for a film that captures the soul of the 1980s without the rose-tinted glasses, this is it. It’s a neon noir that actually earns the "noir" label.

Key takeaways for the modern viewer:

- Study the Craft: Look at the "printing" sequences. They are a masterclass in visual storytelling through process.

- Analyze the Anti-Hero: Compare Richard Chance to modern characters like Vic Mackey or Walter White. You’ll see the DNA of the modern anti-hero right here.

- Appreciate the Practicality: In a world of CGI car crashes, the raw stunt work in the freeway chase is a reminder of what real weight and momentum look like on screen.

- Listen to the Atmosphere: Pay attention to how the Wang Chung score dictates the pacing of the dialogue, not just the action.

To truly appreciate the film, seek out the 4K restoration. The grain, the smog, and the vibrant, sickening colors of Müller’s cinematography deserve to be seen in the highest fidelity possible. It’s not just a movie about L.A.; it’s a movie that feels like L.A. used to be—dangerous, beautiful, and completely indifferent to whether you survive it or not.

Moving Forward with the Film

If you've just finished the movie or are planning a rewatch, your next step should be a deep dive into the work of Robby Müller. His use of natural light and "ugly" urban spaces defined an entire aesthetic of 80s and 90s cinema. Beyond that, compare this film to Friedkin’s other masterpiece, The French Connection. Seeing how his style evolved from the gritty, handheld 70s realism to this heightened, stylized 80s nihilism offers a fascinating look at one of cinema's most uncompromising directors. Finally, track down the original novel by Gerald Petievich. As a former Secret Service agent himself, Petievich provided the procedural backbone that makes the film feel so uncomfortably real.