History isn't a straight line. When you unfold a traditional battles civil war map, you’re usually looking at a series of neat little blue and red boxes, maybe some crisp arrows showing a "flank attack," and a bunch of dates that make the whole thing look like a pre-planned chess match. It’s too clean. It feels like the generals had a God-eye view of the Virginia wilderness or the Tennessee riverbanks. They didn't.

Maps are liars by omission.

💡 You might also like: Why timer 24 hours 60 min 60 seconds Is Actually Your Most Misunderstood Tool

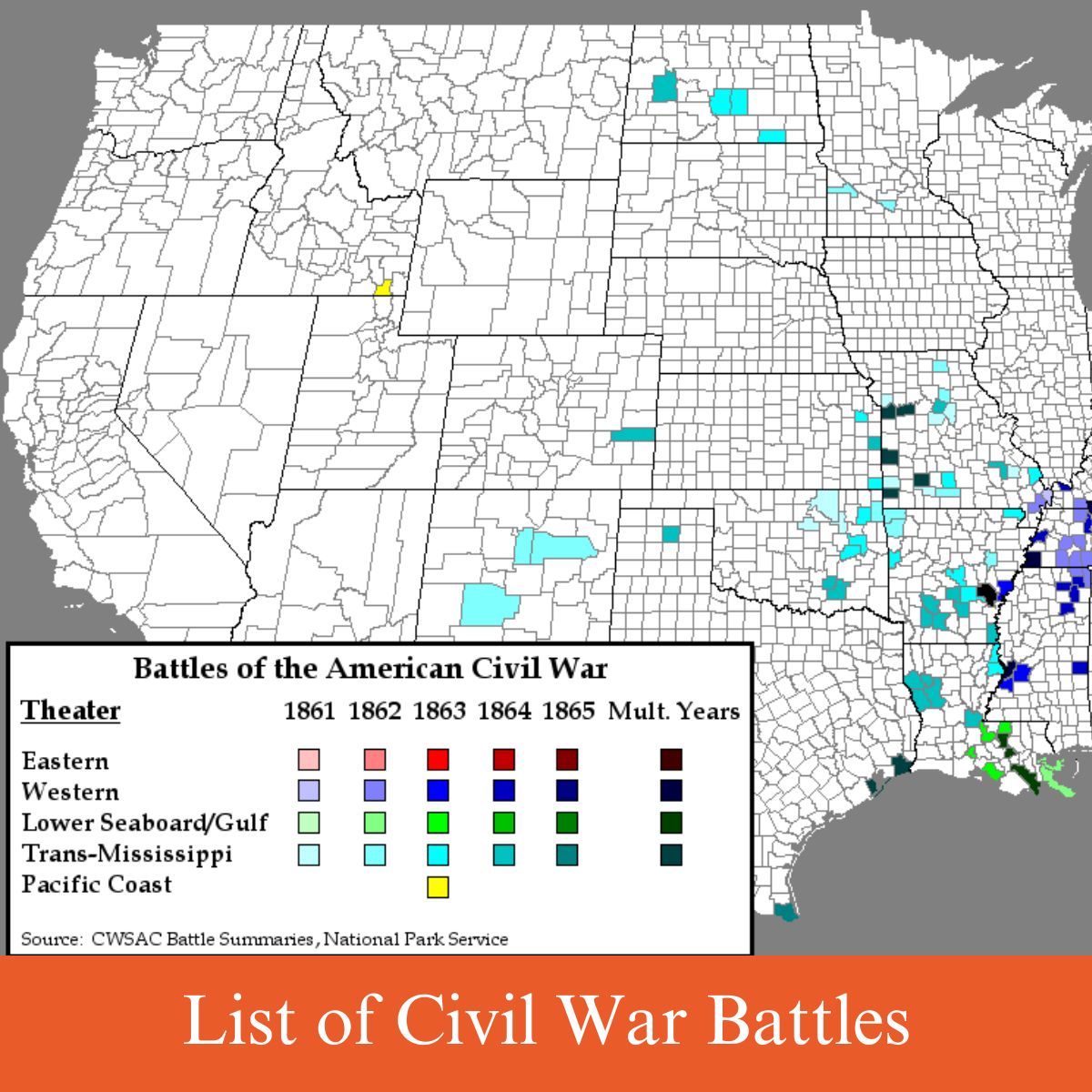

If you really want to understand the American Civil War, you have to look past the static graphics. You have to realize that a map of Gettysburg or Antietam is actually a snapshot of chaos, mud, and terrifyingly bad communication. Most people use these maps to memorize who won where. That's boring. The real value is in seeing the "why"—why a ridge held, why a creek became a graveyard, and why a general like Lee or Grant looked at a piece of parchment and made a choice that cost ten thousand lives.

The Geography of Blood and Why the Terrain Won

Geography dictated everything. Honestly, if you look at a battles civil war map of the Eastern Theater, you start to see a pattern that has nothing to do with politics and everything to do with dirt. The Appalachian Mountains acted like a massive divider. You had the Shenandoah Valley running northeast to southwest, which was basically a "back door" for the Confederacy to threaten Washington D.C.

Rivers were the interstate highways of the 1860s. Look at the Mississippi. Control that, and you split the South in half. Look at the Rappahannock in Virginia. It wasn't just a river; it was a wall. At the Battle of Fredericksburg, Burnside’s Union army had to bridge that water under fire. A map shows a blue line crossing a blue ribbon. The reality was a slaughterhouse where the geography itself—that sunken road at the base of Marye’s Heights—did more work than the Confederate infantry.

Modern cartography tools, like those provided by the American Battlefield Trust, have started using LIDAR. This is cool stuff. It strips away the trees and houses to show the actual "wrinkles" in the ground. You realize a "hill" on an old paper map was actually a complex series of folds where a whole regiment could hide. Suddenly, the movements make sense. You see that a commander wasn't being stupid; he just literally couldn't see over the next rise.

The Misunderstood Scale of the Western Theater

We talk about Virginia a lot. It’s close to the media hubs. But look at a map of the Western Theater. It’s massive. We’re talking about thousands of miles of logistics. While the East was a cramped prize fight in a phone booth, the West was a sprawling brawl.

- Shiloh.

- Vicksburg.

- Chickamauga.

- Atlanta.

These weren't just isolated dots. They were connected by railroads. If you want to understand the war, find a map that overlays the iron rails. The South had fewer of them, and they were different gauges. This meant they couldn't move troops effectively. The Union, meanwhile, was turning the map into a giant machine. When you see the "March to the Sea," don't just look at the path. Look at the distance from the supply lines. Sherman wasn't just marching; he was cutting the umbilical cord of the Confederate economy.

Reading Between the Lines of a Battles Civil War Map

What most people get wrong is thinking a map represents a single moment. It doesn't. A battle map is a four-dimensional event flattened into two dimensions. Take Gettysburg, Day Two. If you look at a map of the struggle for Little Round Top, it looks like a coordinated Union defense. It wasn't. It was a frantic, desperate scramble. Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain wasn't some chess piece; he was a guy who ran out of bullets and told his men to fix bayonets because there was literally nowhere else on the map to go.

There's also the "fog of war" factor. Maps today show exactly where everyone was. In 1863, Lee often had no idea where his cavalry was. Stuart was off joyriding, leaving Lee "blind" in enemy territory. When you look at his movements toward Gettysburg, you should see a man feeling his way through a dark room.

👉 See also: Finding the Right Baby Boy Blessing Outfit Without Losing Your Mind

The Evolution of Cartography

Back then, "maps" were often hand-drawn sketches by engineers who might have been on a horse five minutes ago. They were frequently wrong.

- Inaccurate creek depths.

- Missing roads.

- Misjudged elevations.

At the Battle of the Crater (Petersburg), the Union dug a massive tunnel and blew up a portion of the Confederate line. The map said it was a great idea. The physical reality was a giant hole that the Union troops jumped into, only to realize they couldn't climb out the other side. They were trapped in a bowl of fire. The map didn't show the "steepness" of the rim. That's a lesson in why the three-dimensional world always beats the two-dimensional plan.

Logistics: The Map's Hidden Language

You've probably heard that "amateurs study tactics, professionals study logistics." It's true. A good battles civil war map isn't just about the frontline. It’s about the "tail."

Think about the Overland Campaign in 1864. Grant and Lee were locked in a dance. Grant would attack, fail to break through, and then move "left" (southeast). Look at a map of this. It’s a series of hooks. Grant was trying to get between Lee and Richmond. Lee was moving on interior lines—shorter distances—to stay in front of him. It’s a race. The map shows the geometry of exhaustion. By the time they hit Cold Harbor, both armies were digging in. This is where the map starts looking like World War I. Trenches. Miles of them.

Why the Navy Matters on Your Map

People ignore the water. Big mistake. If your map doesn't show the Union blockade (the Anaconda Plan), you’re missing half the war. The "battles" weren't just at Bull Run or Antietam. They were at the mouth of every major Southern port. The Union Navy was a giant noose. When you look at a map of the coast, every "X" at a port represents a slow strangulation of the Southern economy. No cotton out, no guns in.

Basically, the North used the map to squeeze the South until it popped.

How to Actually Use Maps for Research

Don't just look at one. Compare them. Take an original 1860s reconnaissance map and lay it over a modern Google Earth view. You’ll see that things have changed—suburbs have paved over the "Wheatfield" or the "Peach Orchard"—but the bones of the land remain.

- Check the Contour Lines: If the lines are close together, it’s a steep climb. That’s where the men died.

- Look for the "High Ground": Cemetery Ridge, Culp’s Hill, Marye’s Heights. These names appear on maps for a reason.

- Identify the Chokepoints: Bridges and gaps in the mountains. These were the "valves" that controlled the flow of the war.

The Library of Congress has an incredible digital collection of Civil War maps. Many are hand-colored. You can see the tea stains and the fold marks. These weren't library references; they were tools used in the wind and rain. When you see a map with a smudge on it, that might be where a general’s thumb rested while he decided to send 15,000 men across an open field at Pickett's Charge.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs

To truly master the visualization of these conflicts, you need to go beyond the screen.

First, get your hands on a topographical map. Standard road maps or basic historical diagrams hide the "relief" of the land. Understanding that a 50-foot elevation change was the difference between life and death changes your perspective on every tactical decision made by people like Stonewall Jackson or George Meade.

Second, visit a battlefield if you can, but do it with a map in hand. Stand where the map says "General Longstreet's Corps" stood. Look toward the Union line. Is it further than it looks on paper? Usually, it is. The scale of the "mile-wide" charge at Gettysburg is haunting when you see it in person. The map says it’s a short distance; your legs tell you it’s an eternity under cannon fire.

Third, study the railroad maps of 1861 specifically. Compare them to 1865. The destruction of the Southern rail network is the story of the Confederacy's collapse. Maps of the "Great Locomotive Chase" or the "Burnt District" of Richmond provide a visceral look at the total war aspect that static battle maps often ignore.

Finally, use digital tools like the National Park Service's interactive maps. They often allow you to "scrub" through time, showing how positions changed hour by hour. This removes the "static" lie of the paper map and replaces it with the fluid, terrifying reality of 19th-century combat. History isn't just about what happened; it's about the space it happened in.