Ever stared at a poster in a doctor's office and thought, "Yeah, my back definitely doesn't feel like that"? You aren't alone. Most people look at a body diagram of muscles and see a neat, color-coded map of red fibers and white tendons. It looks clean. It looks organized. It looks... wrong. Real human anatomy is messy. It’s a literal web of connective tissue, overlapping layers, and variations that make you unique. Honestly, the standard anatomical chart is basically just a simplified "tube map" for a system that’s actually a tangled forest.

If you’re trying to fix a nagging shoulder impingement or finally grow your calves, looking at a generic chart might actually be holding you back. We’ve been taught to see muscles as isolated pulleys. Bicep curls for the biceps. Leg extensions for the quads. But that isn't how the body actually moves. Understanding the reality of muscle maps requires looking past the surface.

👉 See also: STAI: Why This Obscure Biotech Metric is Changing How We Think About Aging

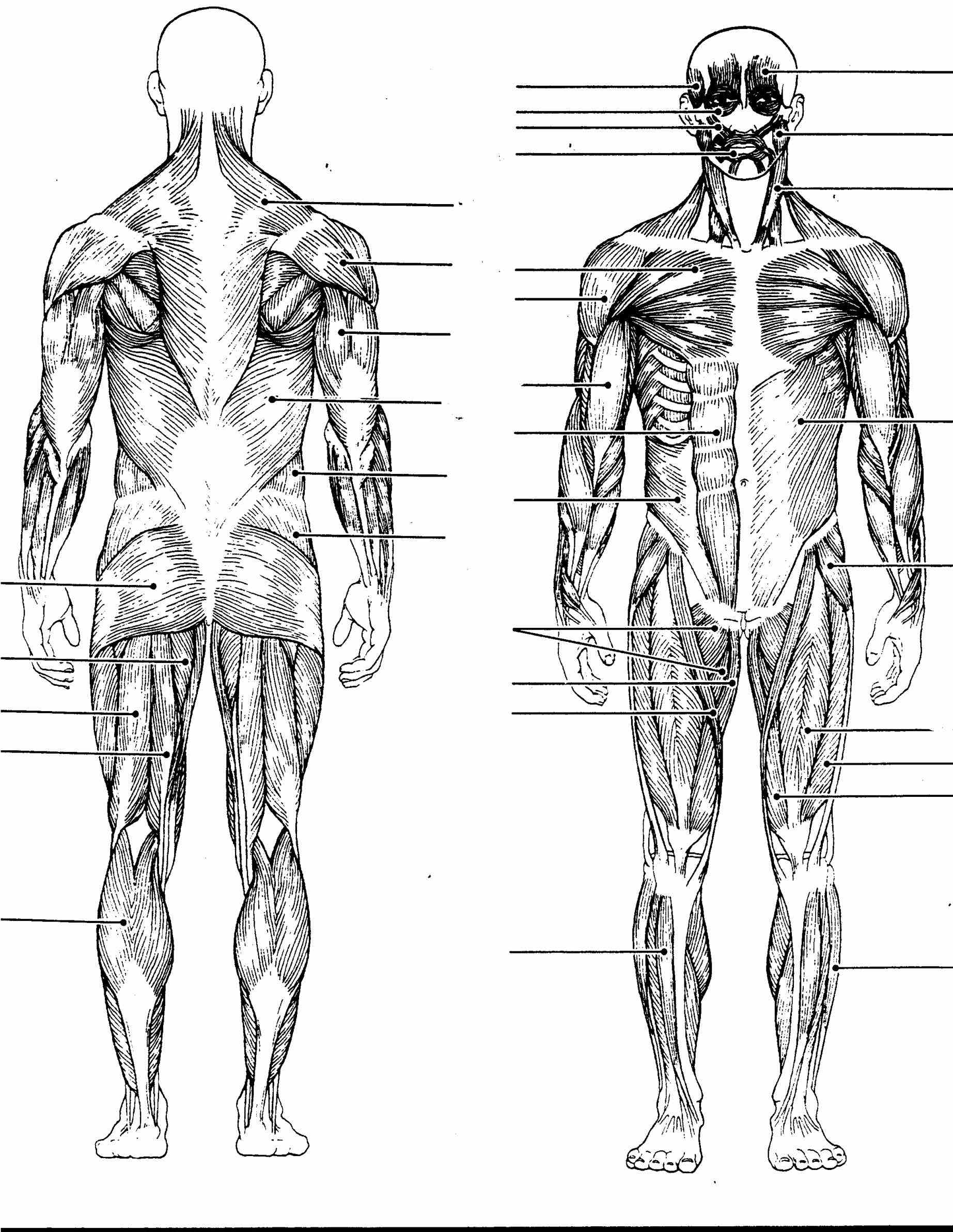

The Anatomy of a Body Diagram of Muscles: What’s Missing?

The biggest lie in your typical body diagram of muscles is the lack of fascia. Dr. Carla Stecco, a renowned professor of anatomy, has spent years documenting how this "white stuff" (the connective tissue) actually dictates how muscles slide against each other. If you look at a classic diagram, the muscles look like individual pieces of meat. In reality, they are encased in a continuous bodysuit of fascia. When you move your arm, you aren't just firing the deltoid; you’re pulling on a chain that stretches all the way to your opposite hip.

Most diagrams focus on the "Superficial Layer." These are the "show" muscles. Think rectus abdominis or the pectoralis major. But beneath those lie the deep stabilizers—the transverse abdominis, the multifidus, and the rotators. Without these hidden players, those big muscles on the chart would basically just tear your skeleton apart. It’s like looking at a car and only seeing the paint job while ignoring the engine block.

Variability is the Rule, Not the Exception

Standard charts show "The Average Human." Guess what? You probably aren't average. Anatomical variations are incredibly common. Some people are born without a palmaris longus muscle in their forearm. Roughly 10% to 15% of the population is missing it, and it doesn't affect their grip strength one bit. Others have an extra muscle in their lower leg called the plantaris. If you’re looking at a body diagram of muscles to diagnose a pain point, you have to realize your internal "wiring" might have a slightly different layout than the textbook.

Then there’s the issue of muscle insertions. One person's bicep might attach slightly further down the radius than another’s. This tiny millimeter of difference changes the mechanical advantage entirely. It’s why some people are naturally "strong" at certain lifts even without much mass. The diagram shows the what, but it rarely explains the where or the how for your specific frame.

Why the Posterior Chain Wins Every Time

Look at the back of any body diagram of muscles. You’ll see the glutes, the hamstrings, and the erector spinae. This is the posterior chain. In our modern "sit-all-day" culture, this side of the diagram is usually screaming for help. While we obsess over what we see in the mirror (the anterior side), the back of the body is doing all the heavy lifting for posture.

The gluteus maximus is the largest muscle in the human body. Period. But on a flat piece of paper, it just looks like a big red blob. What the diagram doesn't show is how it works in tandem with the latissimus dorsi through the thoracolumbar fascia. This "X" pattern across your back is what allows you to walk, run, and throw. If you’re only training the muscles you can see in the mirror, you’re ignoring 60% of your functional power.

The Problem with "Isolation" Thinking

We love to categorize. We say "today is chest day." But the pec major is a complex, fan-shaped muscle. It has different fiber orientations—some run horizontally, some diagonally. A flat body diagram of muscles often fails to show the depth and the "twist" of these fibers. When you press a weight, you aren't just "doing chest." You’re engaging the serratus anterior to stabilize the shoulder blade and the triceps to extend the elbow.

Complexity in the Core

Most people point to their "abs" on a body diagram of muscles and think of the six-pack. That’s just the rectus abdominis. It’s essentially a long, thin muscle that prevents you from leaning too far back. The real "core" is a cylinder. You have the diaphragm at the top, the pelvic floor at the bottom, and the transverse abdominis wrapping around like a corset.

🔗 Read more: Is DayQuil ok while breastfeeding? What you actually need to know before taking it

- Rectus Abdominis: The visible "blocks."

- External/Internal Obliques: The diagonal fibers that handle rotation.

- Transverse Abdominis: The deep "weight belt" that creates internal pressure.

- Multifidus: Tiny muscles along the spine that provide micro-stability.

If you only train what’s visible on the surface of the diagram, you're building a house with no foundation. This is why people with "shredded" abs still end up with lower back pain. Their surface map is great, but their internal structural map is a mess.

Actionable Steps: Using Your Muscle Map Better

Don't just look at a diagram to memorize names for a biology quiz. Use it to understand your own limitations and strengths.

- Feel the Insertion: Instead of just looking at the chart, poke your own muscles while they move. Find where your bicep actually turns into a tendon near your elbow. That’s your personal "anchor point."

- Think in Chains: Next time you look at a body diagram of muscles, try to trace a line from your big toe to your neck. Notice how the muscles overlap. When you have a tight neck, it might actually be coming from a tight calf pulling on the entire posterior line.

- Test for Symmetry: Use a mirror and compare yourself to the "perfect" diagram. Most humans have one shoulder slightly higher or one leg slightly more muscular. This isn't a "defect." It's a reflection of how you’ve lived, worked, and moved.

- Prioritize the "Invisible": Spend more time on the muscles that look small or are hidden under layers on the chart. The rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis) is way more important for your long-term health than a massive chest.

Stop treating your body like a collection of separate parts. The body diagram of muscles is a helpful tool, but it's just a map. And as the saying goes, the map is not the territory. Your territory is a living, breathing, adapting system of tension and compression. Treat it like a whole unit, and it’ll start behaving like one. Focus on the connections, not just the labels. That’s how you actually master your own anatomy.