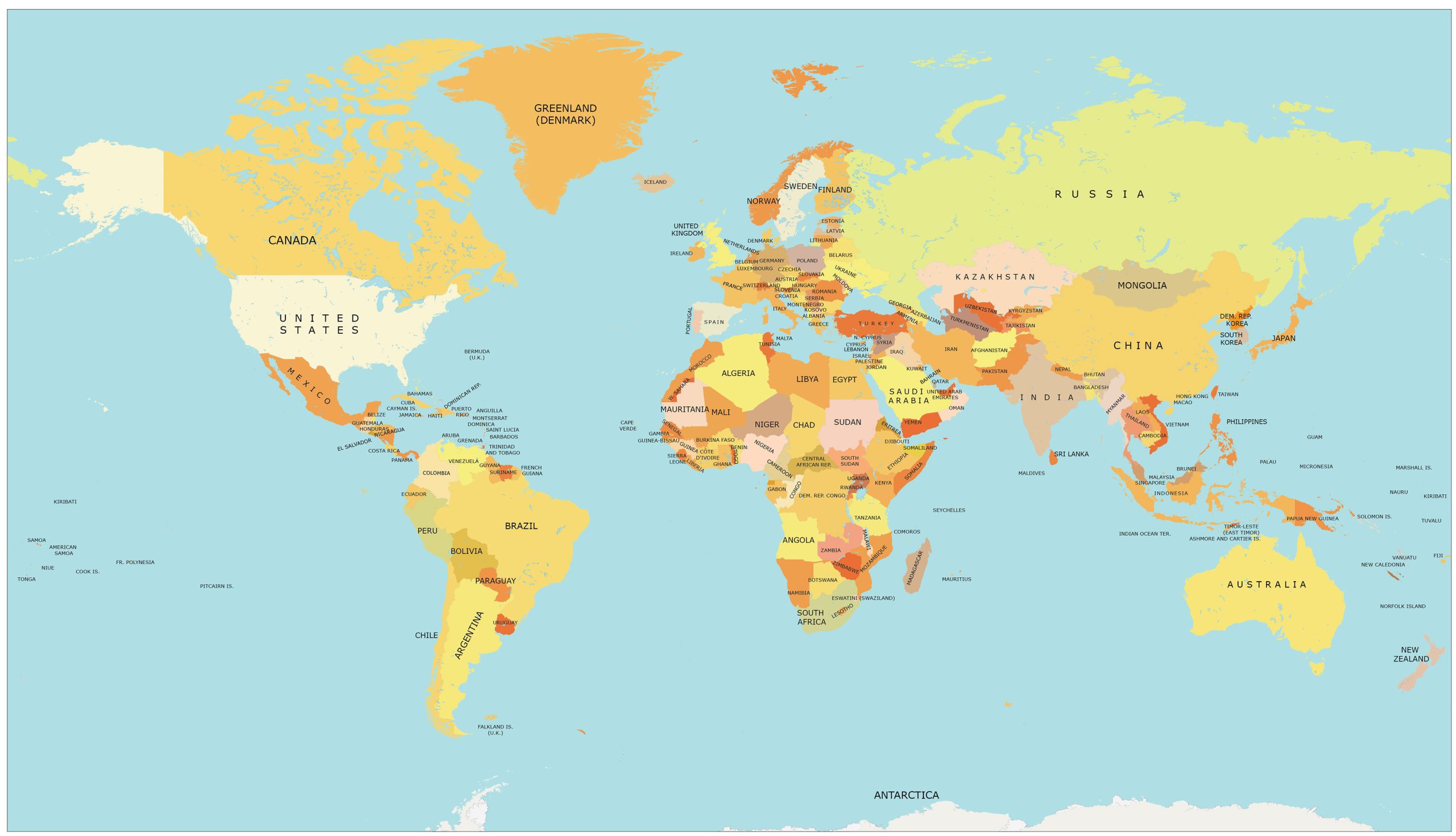

Maps are weird. We look at a map of the world and all the countries and think we’re seeing reality, but honestly, we’re just looking at a very useful compromise. You’ve probably seen the viral videos showing how huge Africa actually is compared to Greenland. It’s a shock because our brains are hardwired to trust the visual data on the paper or screen. But here’s the thing: you can’t flatten a sphere onto a rectangle without stretching something. It’s mathematically impossible.

If you peel an orange and try to press the skin flat, it rips. To keep a map from ripping, cartographers have to stretch it. Usually, they stretch the parts near the poles. This is why the Mercator projection—the one you saw in every geography classroom—makes Europe look massive and South America look tiny. In reality, South America is nearly double the size of Europe.

The Political Maze of Modern Borders

Defining a map of the world and all the countries isn't just about geography; it’s about who is talking. If you ask the United Nations, there are 193 member states. But if you ask a FIFA official or the Olympic Committee, that number jumps significantly.

Think about Taiwan. Or Kosovo. Or the Holy See.

Geography is messy. Most people think borders are these permanent, etched-in-stone lines, but they’re constantly shifting. Look at the recent history of South Sudan, which became the world’s youngest sovereign state in 2011. Even today, there are dozens of "frozen conflicts" where two countries claim the exact same patch of dirt. The Map of the World is a living document, not a static image.

Size Matters (And We Get It Wrong)

We need to talk about the Gall-Peters projection. It’s that "ugly" map where the continents look like they’re melting or stretching downwards. While it looks strange, it’s actually much more accurate regarding landmass area.

💡 You might also like: Dream Hotel Miami Beach: What Most Travelers Get Wrong About This Collins Ave Icon

When you look at a standard map of the world and all the countries, Greenland looks like it could swallow Africa whole. It can’t. Africa is actually fourteen times larger than Greenland. You could fit the USA, China, India, and most of Europe inside the borders of Africa, and you’d still have room for change.

Why does this happen? Most maps we use today are based on navigation. Sailors needed to maintain a constant bearing, and the Mercator projection allows for that. It keeps the shapes of the countries mostly correct so you don't crash your ship, but it sacrifices the actual size. This "size distortion" has arguably shaped how we view the importance of certain nations for centuries.

The Problem with 195 Countries

You’ll often hear the number 195 tossed around. That’s the 193 UN members plus Palestine and Vatican City. But that's a very Western-centric way of looking at a map of the world and all the countries.

If you go to Somaliland, they have their own currency, their own government, and their own police force. They’ve been functioning as a country for decades. Yet, look at a standard map, and it’s just part of Somalia. The same goes for Transnistria or Abkhazia. There is a massive gap between "de facto" independence (actually running a country) and "de jure" recognition (being on the official map).

Islands, Atolls, and Disappearing Acts

Climate change is literally rewriting the map. For nations like Kiribati or the Marshall Islands, the map of the world and all the countries is shrinking. These aren't just lines on a page; they are homes that are physically disappearing under the Pacific.

Some of these nations are already buying land in other countries—like Fiji—to relocate their entire populations. It raises a wild legal question: if a country’s land is underwater, is it still a country? Do they keep their seat at the UN? Do they keep their fishing rights? We don't really have a plan for that yet.

👉 See also: Is the Get Out Pass Utah Actually Worth It? A Brutally Honest Look at the Numbers

Navigating the Digital Map

Google Maps and Apple Maps have changed how we interact with the globe. We no longer see the whole world; we see the blue dot. We see ourselves. This "micro-mapping" is great for finding a taco truck, but it’s terrible for understanding global context.

Digital maps also change based on where you are. If you open a map in India, the borders of Kashmir might look different than if you open that same map in Pakistan. Tech companies have to follow local laws, which means the "truth" of a map of the world and all the countries is now geofenced. It’s a personalized reality.

The Continental Drift of Definitions

We were all taught there are seven continents. Or six, if you’re in Europe or Latin America. Or five, if you follow the Olympic rings.

Even the definition of a continent is shaky. Is Europe actually a continent, or just a massive peninsula of Asia? Geologically, it’s Eurasia. The division is cultural and historical, not based on tectonic plates. And then there’s Zealandia—a massive landmass submerged under New Zealand that scientists now argue should be considered the eighth continent.

How to Actually Read a Map

To get a real sense of the map of the world and all the countries, you have to look at multiple projections.

- Winkel Tripel: This is what the National Geographic Society uses. It tries to balance the distortion of area, direction, and distance. It’s not perfect, but it’s probably the most "honest" flat map we have.

- The Globe: Seriously. If you want to see the world without lies, buy a physical globe. It’s the only way to see the true spatial relationship between Russia and North America (they’re much closer than you think) or the true scale of the Pacific Ocean.

- AuthaGraph: This is a Japanese invention that folds the world into a 3D shape before flattening it. It’s arguably the most accurate representation of land and water proportions ever made.

Actionable Steps for the Globally Curious

Stop relying on the wall map in your office. If you want to understand the world, start by using tools like The True Size Of, a website that lets you drag countries around to see how they actually compare when you account for distortion.

Next, diversify your sources. Don't just look at Western-produced maps. Check out the World Mapper project, which resizes countries based on things like population, wealth, or even carbon emissions. It’s a trip to see the world where India and China dwarf everything else based on people rather than dirt.

Finally, keep an eye on the news regarding the "UN Convention on the Law of the Sea." As the Arctic ice melts, new shipping routes are opening up, and the map of the world and all the countries is about to get a lot more crowded as nations scramble to claim the North Pole. The map isn't finished. It never will be.