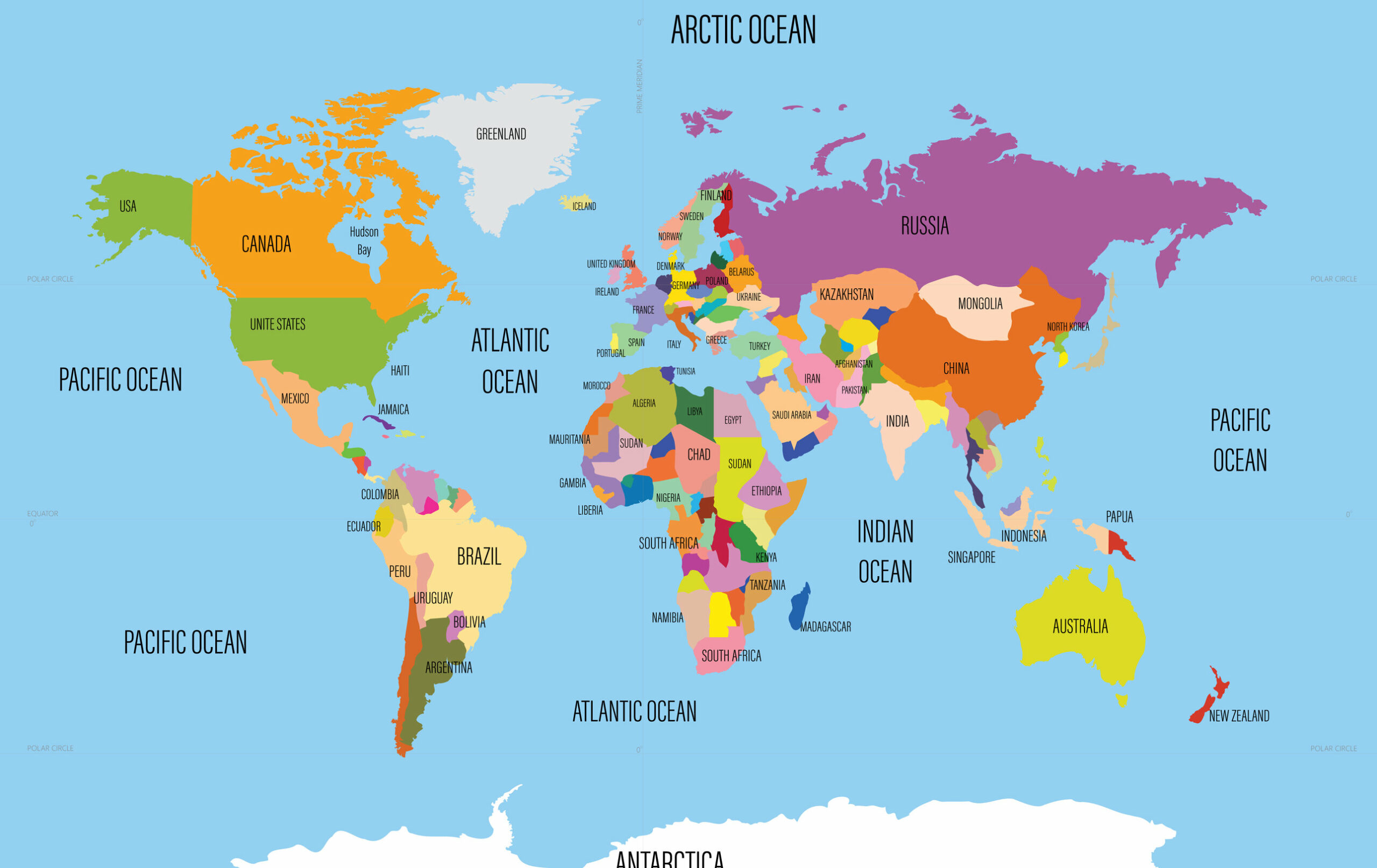

You’ve probably spent your whole life looking at a flat lie. Every time you open a world map and oceans are spread out across a rectangular screen or a paper poster, you’re seeing a version of Earth that doesn't actually exist. It’s distorted. It’s stretched. Honestly, it’s kinda weird how we still rely on maps designed in the 1500s to understand a 21st-century planet.

Maps are basically just flat representations of a curved reality. You can't peel an orange and lay the skin flat without it tearing, right? Mapmakers have been wrestling with that exact problem for centuries. They usually choose to preserve direction at the expense of size, or size at the expense of shape. This isn't just a nerdy cartography debate. It actually changes how we perceive power, travel, and the massive scale of our global waters.

The Great Mercator Deception

Gerardus Mercator changed everything in 1569. He needed a map that helped sailors navigate. If you draw a straight line on his map, you can follow a constant compass bearing. That was a massive deal for explorers. But to make those straight lines work, he had to stretch the areas near the poles.

📖 Related: Hershey Sweet Lights: What Most People Get Wrong About This Pennsylvania Tradition

This is why Greenland looks as big as Africa on many maps. In reality? Africa is fourteen times larger. You could fit Greenland, the United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside Africa with room to spare. When we look at a world map and oceans appear to be secondary to these giant northern landmasses, we’re falling for a 500-year-old navigation hack.

People often forget how much the Pacific Ocean dominates the globe. It's huge. Like, mind-bogglingly huge. It covers about one-third of the entire Earth's surface. If you look at the Pacific from the right angle on a globe, you won't see much land at all. Just blue. Endless blue. The Mercator projection makes the Atlantic look like a central highway, but the Pacific is the real titan. It's deeper and wider than most people can even visualize.

The Five Oceans (Or Is It One?)

For a long time, we talked about the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Arctic. Then, in 2021, the National Geographic Society officially recognized the Southern Ocean around Antarctica. It’s defined by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. That’s a fast-moving, cold water stream that keeps the bottom of the world frozen.

- The Pacific: The biggest and deepest. It holds the Mariana Trench, which goes down about 36,000 feet. If you dropped Mount Everest into it, the peak would still be over a mile underwater.

- The Atlantic: It’s growing. Literally. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a volcanic mountain range underwater where tectonic plates are pulling apart, adding new seafloor every year.

- The Indian Ocean: This one is the warmest. Because it's so warm, it doesn't hold as much oxygen, which affects the kind of marine life that can thrive there.

- The Southern Ocean: It's the "newest" officially recognized one, but it’s arguably the most important for regulating global climate.

- The Arctic: The smallest and shallowest. It’s mostly covered by ice, though that’s changing faster than anyone expected.

Technically, there is only one "Global Ocean." All these bodies of water are connected. If you drop a message in a bottle off the coast of New York, it could eventually end up in Perth or Tokyo. The water is constantly moving in a massive conveyor belt called thermohaline circulation. It takes about 1,000 years for a single drop of water to complete the whole circuit.

Why the World Map and Oceans Look Different Today

Technology has moved past paper. We have bathymetric maps now. These use sonar and satellite altimetry to map the "mountains" and "valleys" on the ocean floor. Before we had this, we thought the bottom of the ocean was a flat, muddy wasteland.

📖 Related: How Far is Fontana From Los Angeles: What Most People Get Wrong

We were wrong.

The ocean floor is more rugged than the surface of the moon. There are "seamounts" that are taller than any mountain on land. There are giant trenches where the earth's crust is being swallowed back into the mantle. When you look at a modern world map and oceans are shown with their topographical detail, you see the scars of plate tectonics.

The most accurate map we have today is arguably the AuthaGraph. It was created by Japanese architect Hajime Narukawa. It manages to represent the relative sizes of landmasses and oceans almost perfectly by folding the globe into a tetrahedron and then flattening it. It looks a bit strange—kinda like a jigsaw puzzle that hasn't been put together right—but it’s the closest we can get to the truth on a flat surface.

The Economic Reality of Water

The way we draw maps affects how we think about trade. Most people don't realize that 90% of everything you own—your phone, your shoes, the coffee in your kitchen—arrived via the ocean. Shipping lanes are the invisible threads on the world map.

The "Chokepoints" are the most critical spots. Think of the Strait of Malacca between Malaysia and Indonesia. Or the Suez Canal. When a ship gets stuck in the Suez, the entire global economy holds its breath. These tiny strips of water on a map represent trillions of dollars in trade.

Climate change is also redrawing the map. As Arctic ice melts, the "Northwest Passage" is becoming a real shipping route. This would cut weeks off the time it takes to get goods from Asia to Europe. Countries like Russia and Canada are already fighting over who owns these new watery "roads." The map isn't static. It’s a living, shifting thing.

Practical Steps for Understanding the Globe

Stop looking at flat maps if you want to understand scale.

- Use a Globe: It sounds old school, but a physical globe is the only way to see how big the Pacific really is. You’ll realize that the flight from LA to Singapore isn't just a long hop; it's a journey across a massive portion of the planet.

- Check the Peters Projection: Look up a Gall-Peters map. It looks "stretched" vertically, but it shows the correct size of countries. It’s a shock to see how tiny Europe actually is compared to South America.

- Explore Bathymetry: Use tools like Google Ocean (within Google Earth) to look at the ridges and trenches. Seeing the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in 3D changes your perspective on how the earth is actually built.

- Follow Current Trackers: Look at real-time maps of ocean currents like the Gulf Stream. It’ll help you understand why London is much warmer than Newfoundland, even though they are at similar latitudes.

The ocean isn't just the space between the countries. It is the dominant feature of our planet. When you look at a world map and oceans seem like background noise, remember that you’re looking at the engine of our climate, the highway of our economy, and the final frontier of exploration on Earth. We've mapped the surface of Mars better than we've mapped the deep sea. There is still so much we don't know about what’s happening three miles down.

Understanding the map is the first step in understanding the world. Just don't trust the flat ones too much. They're lying to you for the sake of convenience.

To get a better handle on the reality of our planet, start by comparing the land area of your own country to a "true scale" map tool online. You might find that your corner of the world is a lot smaller—or larger—than you were taught in school.