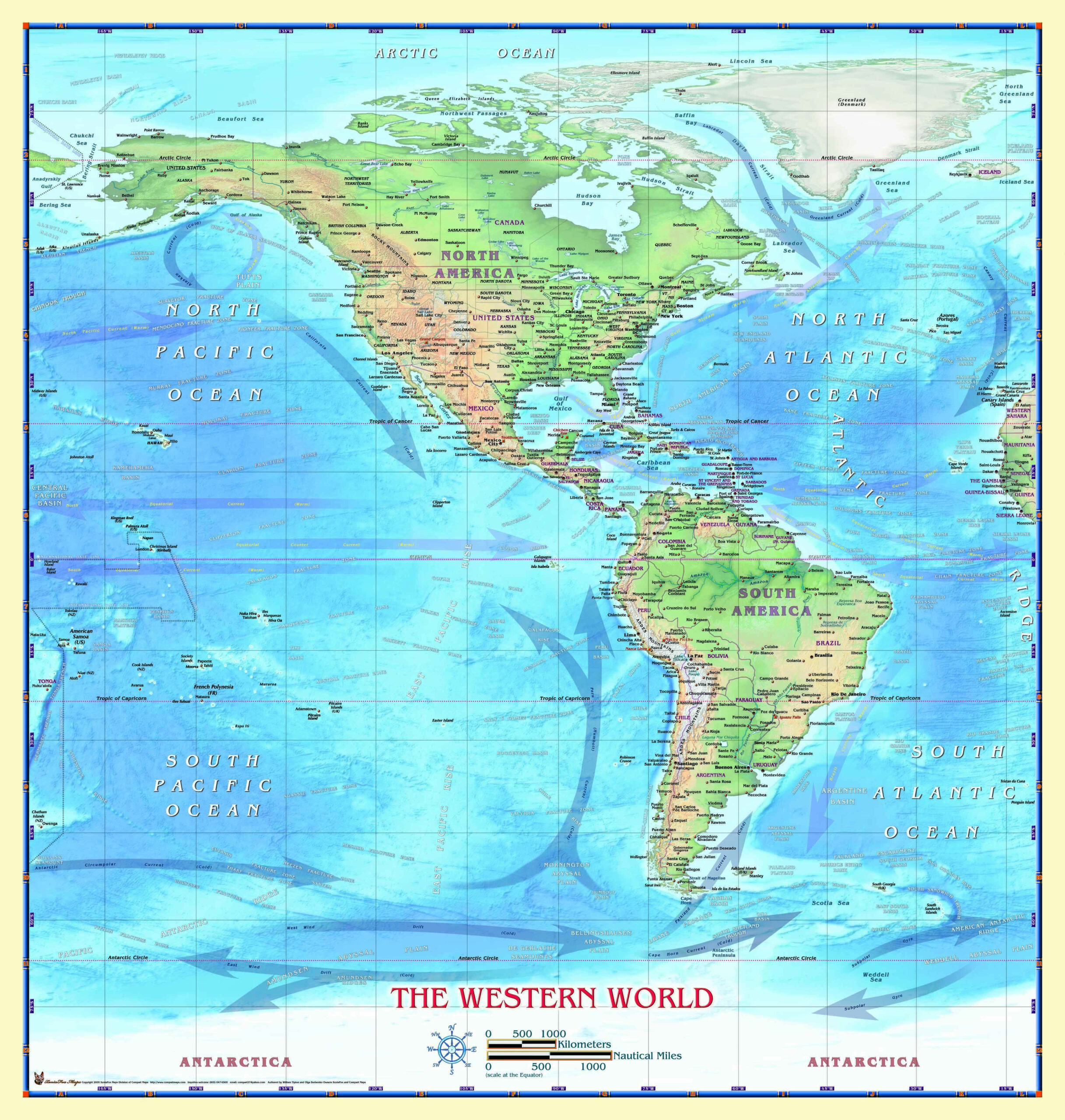

Maps are liars. Seriously. If you look at a standard world map of western hemisphere projections, you’re seeing a flat version of a round world, which means something has to give. Usually, it's the size of the continents. We’ve all seen those classroom maps where Greenland looks roughly the size of Africa, even though Africa is actually fourteen times larger. It's wild how much our visual understanding of "the West" is shaped by 16th-century sailors trying not to crash into rocks.

The Western Hemisphere is basically the Americas, the Atlantic, the Pacific, and a tiny slice of Europe and Africa. It’s defined by the Prime Meridian and the 180th meridian. But here is where it gets kinda weird. People often use "Western Hemisphere" as a synonym for "The Americas." Geographically? That’s not quite right. Parts of the United Kingdom, France, Spain, and a massive chunk of West Africa actually sit inside the Western Hemisphere.

The Mapping Glitch You Probably Missed

Most people think the Western Hemisphere is just North and South America. It’s a common mistake. If you’re looking at a world map of western hemisphere data, you'll notice the line cuts straight through Greenwich, London. This means that if you’re standing in certain parts of Spain or Algeria, you’re technically in the "West" along with someone in New York or Lima.

🔗 Read more: Gunstock Inn & Resort Gilford NH: What Most People Get Wrong

Mapping this specific half of the globe isn't just about drawing lines. It’s about the "New World" identity. Historically, the term was popularized during the Cold War to distinguish the "democratic" West from the Eastern Bloc. But geography doesn't care about politics. The physical reality of the Western Hemisphere includes the Caribbean, the vastness of the Pacific islands like Hawaii and American Samoa, and the icy reaches of Antarctica’s western side.

The Mercator Mess

Why do maps look so distorted? Gerardus Mercator created his map in 1569. It was a tool for navigation. It preserved directions, which was great for captains but terrible for anyone trying to understand the actual landmass.

On a standard Mercator projection of the Western Hemisphere, North America looks gargantuan compared to South America. In reality, South America is nearly 7 million square miles. It's massive. Brazil alone is almost the size of the contiguous United States. When we look at these maps, our brains subconsciously assign "importance" to size. This "Northern bias" is a huge topic in cartographic circles because it subtly influences how we perceive global power and resources.

Navigating the Americas and Beyond

If you’re traveling across the Western Hemisphere, you’re dealing with an incredible range of biodiversity. You have the Arctic tundra in Northern Canada, the Amazon rainforest in Brazil, and the windswept plains of Patagonia.

Let's talk about the Andes for a second. This mountain range is the longest continental mountain range in the world. It stretches about 4,350 miles along the western edge of South America. On a world map of western hemisphere terrain, it looks like a thin spine. In person, it's a colossal wall that dictates the climate for an entire continent. It creates the Atacama Desert—one of the driest places on Earth—by blocking moisture from the east.

- North America: Dominated by the Canadian Shield, the Great Plains, and the Rockies.

- The Caribbean: A massive archipelago of over 7,000 islands, most of which sit on the Caribbean Plate.

- South America: Home to the Amazon River, which carries more water than the next seven largest rivers combined.

Geology is basically the boss here. The "Ring of Fire" circles the Pacific side of the Western Hemisphere. This isn't just a catchy name; it’s a zone of intense volcanic and seismic activity. From the Aleutian Islands in Alaska down to the southern tip of Chile, the earth is constantly shifting. This is why cities like San Francisco, Mexico City, and Santiago are so prone to earthquakes.

The Cultural Divide vs. The Geographic Divide

There is a huge difference between the "Cultural West" and the "Geographic Western Hemisphere." This trips people up all the time. Australia is culturally "Western" but sits entirely in the Eastern Hemisphere. Meanwhile, countries like Ghana or Mali have territory in the Western Hemisphere but aren't what people mean when they say "the West."

When cartographers design a world map of western hemisphere perspectives, they have to decide where to center the view. If you center it on the Americas, you lose the context of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. These oceans aren't just empty spaces; they are the highways of history. The Atlantic crossing transformed the hemisphere through the Columbian Exchange—the massive transfer of plants, animals, and, unfortunately, diseases between the Old and New Worlds.

Think about the potato. It’s a staple in Ireland and Idaho. It originated in the Andes of South America. Without the maps that charted the Western Hemisphere, the global food supply would look completely different today. Honestly, the world would be a lot hungrier.

How to Actually Read a Western Hemisphere Map

If you want to understand the scale of this half of the planet, you have to look at different projections. Stop relying on Mercator. Check out the Gall-Peters projection. It’s "equal-area," meaning it shows the actual relative sizes of the continents. South America suddenly looks much longer and more imposing, while Greenland shrinks down to its rightful size.

Another one to look for is the Robinson projection. It’s a compromise. It doesn’t get the area or the angles perfectly right, but it "looks" more natural to the human eye. Most modern atlases use something like this to show the Western Hemisphere because it minimizes the stretching at the poles.

📖 Related: Why staying at the Hollywood Media Hotel Berlin feels like a movie set

Essential Landmarks You Should Know

When you study the map, look for the Panama Canal. It’s a tiny sliver of a waterway, but it’s the most important geopolitical point in the hemisphere. Before it opened in 1914, ships had to sail all the way around Cape Horn at the tip of South America—a brutal and dangerous journey. The canal literally sliced a continent in half to save 8,000 miles of travel.

Also, keep an eye on the 100th Meridian in the United States. It roughly bisects the country. Historically, it was the "breadbasket" line—east of the line was humid and good for farming, west of it was arid and required irrigation. Climate change is actually shifting this line eastward, changing the geography of American agriculture in real-time.

Actionable Steps for Map Enthusiasts

If you're trying to master the geography of this region or planning a massive trip across the Americas, don't just stare at a Google Map on your phone. Digital maps are great for finding a coffee shop, but they suck at showing scale because they use Web Mercator.

- Use an Earth Ball (Globe): It’s the only way to see the Western Hemisphere without distortion. You’ll realize how close Alaska actually is to Russia (only about 55 miles at the Bering Strait).

- Compare Projections: Go to a site like "The True Size Of" and drag South American countries over Europe or North America. It’ll blow your mind how big Brazil actually is.

- Study Tectonic Plates: To understand why the map looks the way it does—why there are mountains in the west and plains in the east—look at a map of the North American and South American plates. The geography is just a result of these massive slabs of rock crashing into each other.

- Check the Time Zones: The Western Hemisphere spans roughly 12 hours of time zones. Following the lines of longitude on the map will help you understand why it can be noon in New York but only 9:00 AM in Los Angeles and 2:00 PM in Rio de Janeiro.

The world map of western hemisphere isn't just a drawing of land and water. It's a snapshot of a changing planet. Coastlines are shifting due to rising sea levels, and new islands are being born from volcanic activity in the Pacific. To really "see" the map, you have to look past the borders and see the physical forces that shaped the land long before we started drawing lines on it.