Ever stared at a Wyoming and Idaho map and thought, "That looks like a simple enough line"? Honestly, it's not. Most people see two big, rectangular-ish blocks in the American West and assume the border is just some arbitrary pencil stroke made by a bored bureaucrat in D.C.

It wasn't.

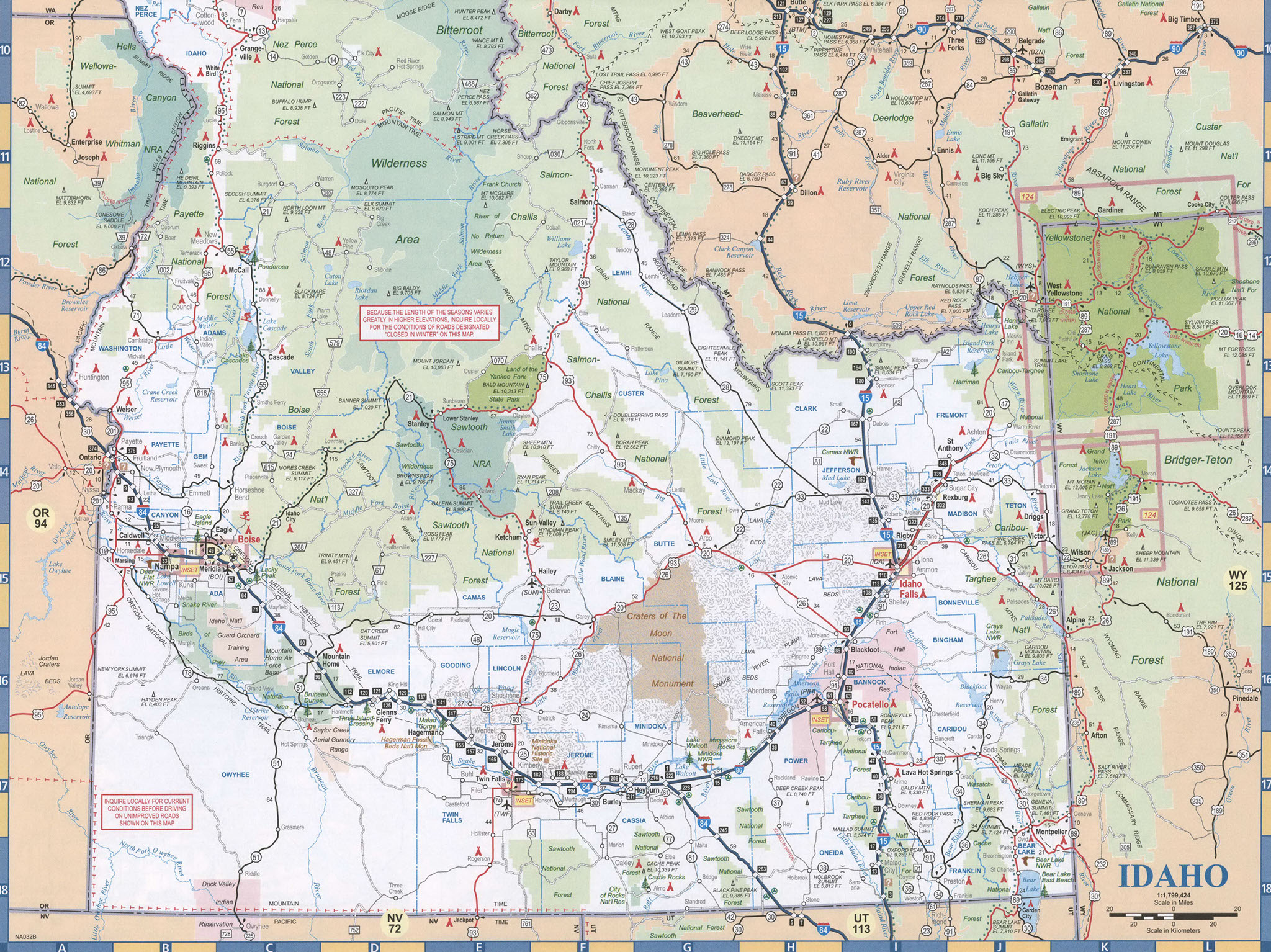

That jagged, zig-zagging western edge of Wyoming is actually a battlefield of historical ego, drunken (maybe) surveyors, and some of the most vertical geography on the planet. If you're looking at a map of these two states, you aren't just looking at political lines; you're looking at a 150-year-old wrestling match between the Rockies and the people who tried to tame them.

Why the Border Isn't a Straight Line

Look closely at where Idaho and Wyoming meet. You've got this long, vertical stretch that suddenly feels "off" as it moves north. Historically, Idaho Territory was actually massive—like, "taking up most of the West" massive. In 1863, Idaho included all of present-day Montana and Wyoming.

Basically, Idaho was the giant of the Rockies.

But then Congress started carving it up like a Thanksgiving turkey. When they finally got around to setting the Wyoming-Idaho boundary in 1868, they didn't just use a ruler. They were following the 42nd parallel at the bottom (where they meet Utah) and then heading north.

There’s this famous legend that the surveyors were drunk and missed the Continental Divide, which is why Montana got a bigger slice of the pie. While the "drunk surveyor" story is mostly just a fun campfire tale, the reality is that the 1874 survey led by A.V. Richards was a brutal slog through "the roughest mountains and deepest canyons." They weren't drunk; they were just trying not to die while lugging heavy brass instruments over 10,000-foot peaks.

The Geologic "Smile" Across the Map

If you pull up a satellite version of a Wyoming and Idaho map, you'll notice a massive, dark crescent shape cutting across southern Idaho and hooking into northwestern Wyoming. Geologists call this the Snake River Plain.

I like to think of it as the "scar" left by the Yellowstone Hotspot.

As the North American tectonic plate slowly drifted southwest, this stationary plume of magma underneath basically burned a path through the crust. It’s why southern Idaho is relatively flat and covered in volcanic basalt, while the areas just north and south are jagged mountains.

- Yellowstone's Core: Most of the park is in Wyoming, but look at the map—there’s a tiny sliver of Idaho in there.

- The Overthrust Belt: This is a fancy way of saying the rocks here are folded like a piece of paper. It runs right along the border and is the reason the area is so rich in oil, gas, and weird minerals.

- The Snake River: It starts in Wyoming (Yellowstone/Grand Teton area), dives into Idaho, and creates the lifeblood of Idaho’s agriculture.

Navigating the Teton Pass and Beyond

If you’re actually planning a road trip using a Wyoming and Idaho map, you need to respect the Teton Pass. This is State Highway 22 in Wyoming, which becomes Highway 33 in Idaho. It’s the primary link between Jackson Hole, WY, and Victor, ID.

Don't underestimate this road. It has a 10% grade.

For the uninitiated, a 10% grade means your brakes will be screaming if you aren't careful. People often stay in Victor or Driggs, Idaho, because it’s cheaper than Jackson, but they forget they have to climb over a mountain every morning. On the map, it looks like a 20-minute jump. In a snowstorm? It's a different world.

🔗 Read more: Why San Francisco de Asis Mission Church in Taos Still Matters

Essential Landmarks Along the Border

- Bear Lake: Half in Idaho, half in Utah, and just a stone's throw from the Wyoming line. It's called the "Caribbean of the Rockies" because the limestone minerals turn the water an insane turquoise blue.

- The Salt River Range: This is the massive wall of rock you see looking east from the Idaho side of the border near Afton, Wyoming.

- Grand Targhee Resort: Here is a map quirk for you. This ski resort is technically in Wyoming, but the only way to drive to it is through Alta, Wyoming, which you can only reach via Driggs, Idaho. It’s a geographical headache that produces some of the best powder in the world.

Why This Map Still Matters in 2026

In a world of GPS, why do we care about a Wyoming and Idaho map? Because the "Line" is becoming a cultural and economic divide.

Wyoming has no state income tax. Idaho does. This has created a weird phenomenon where people work in one state and live in the other, causing a massive "commuter crawl" over the passes. You’ve got billionaires in Jackson pushing the "working class" over the border into Teton Valley, Idaho.

When you look at the map now, you aren't just seeing geography; you're seeing the "New West" struggle.

The physical map hasn't changed much since the 1800s, but the way we use it has. We use it to find the last bits of "wild." You can still go to the Caribou-Targhee National Forest—which straddles the line—and get lost for three days without seeing another human. That’s the real value of these maps. They show us where the pavement ends and the real stuff begins.

Actionable Next Steps

If you're using this map for travel or research, do these three things:

- Check the passes: Before driving, use the WYDOT or Idaho 511 apps. The map doesn't show you the three feet of snow on Teton Pass.

- Look for the "Three Corners" marker: If you're a map nerd, you can actually hike to the spot where Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah all meet. It’s southwest of Cokeville, WY.

- Explore the "West Side" of the Tetons: Most people see the Tetons from the Wyoming side. Use your map to find the Idaho side (the "quiet side") for a completely different perspective of the peaks.

The border might be a man-made invention, but the land it cuts through is anything but orderly. Whether you're tracking the Snake River or trying to find a cheaper hotel room, the Wyoming and Idaho map is your guide to the most rugged, beautiful, and geologically confusing part of the United States.