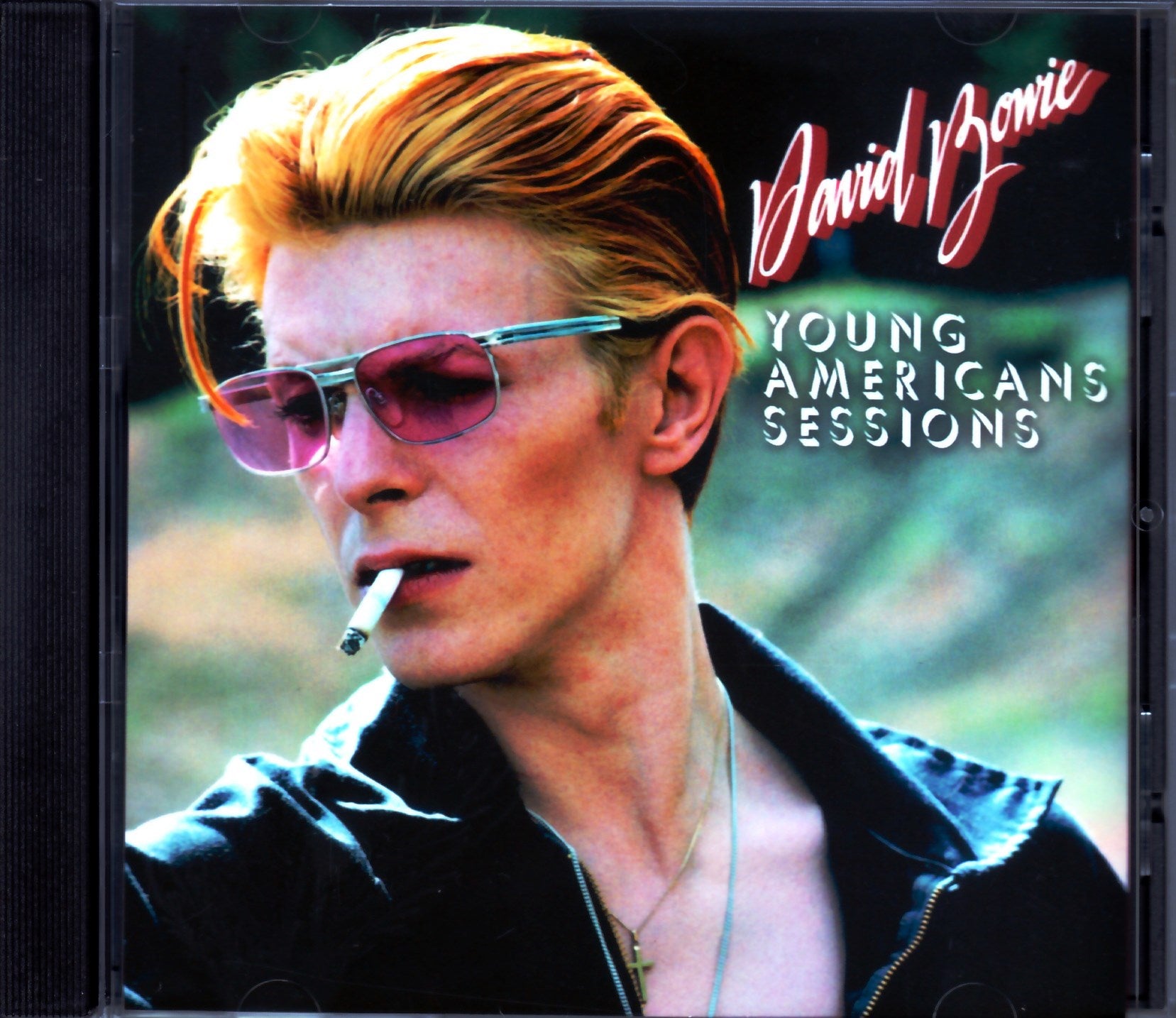

David Bowie was bored. Or maybe he was just restless. By 1974, the glitter was falling off the glam rock movement he’d essentially birthed. Ziggy Stardust was dead, the Spiders from Mars were history, and Bowie was looking for something that felt more like the streets of Harlem than the rings of Saturn. He found it in Philadelphia.

Honestly, people often overlook how risky Young Americans David Bowie actually was for him. It wasn't just a costume change; it was a total sonic hijacking. He went from theatrical rock to what he jokingly—and somewhat cynically—called "plastic soul."

The Sigma Sound Sessions: Milk, Peppers, and Magic

Bowie didn't just walk into a studio; he took over Sigma Sound Studios in Philly. He brought in Carlos Alomar, a guitarist who had played with James Brown and didn't care much for Bowie’s glam pedigree. Alomar brought his wife, Robin Clark, and a then-unknown singer named Luther Vandross.

Yeah, that Luther Vandross.

At the time, Luther was just a kid with a golden voice. During the sessions, Bowie overheard Luther arranging some complex backing vocals for the title track. Instead of being the "rock star," Bowie stepped back. He basically handed Luther the keys to the vocal arrangements. You can hear that influence throughout the album—it's dense, gospel-tinged, and deeply American.

The "Plastic Soul" Dilemma

Bowie knew he was a white "limey" (his words) dipping into Black American music. He called it "plastic soul" because he felt it was a synthetic version of the real thing, filtered through a British perspective. It was self-deprecating but also honest.

He was living on a diet of red peppers, milk, and enough cocaine to fuel a small jet. He looked like a ghost—thin, pale, and constantly on edge. Yet, the music coming out of the speakers was warm and lush. It’s a wild contradiction. The title track "Young Americans" remains a masterpiece of lyrical density, cramming in everything from Nixon to the McCarthy era in a breathless five minutes.

What Happened in New York with John Lennon

The album was mostly done, but it wasn't quite finished. Bowie moved the party to Electric Lady Studios in New York in January 1975. That’s where things got weird in the best way possible.

He met John Lennon.

They started jamming. They did a cover of "Across the Universe," which... look, it’s polarizing. Some fans hate it. But the real gold came from a guitar riff Carlos Alomar had been kicking around. Lennon started singing the word "Aim" over the riff. Bowie, ever the lyricist, flipped it to "Fame."

- Fame became Bowie's first No. 1 hit in the U.S.

- Lennon sang the high-pitched "Fame!" backing vocals.

- They wrote the whole thing in a single day.

It was a total fluke. Bowie actually didn't think much of the song at first, yet it became the cornerstone of the record’s success. It knocked "Rhinestone Cowboy" off the top of the charts. Think about that for a second.

The "Sigma Kids" and the First Listen

One of the coolest stories about the Young Americans David Bowie era is the "Sigma Kids." These were about a dozen fans who camped outside the studio every single night. They weren't just groupies; they were part of the furniture.

On the final night of recording, Bowie did something very un-rockstar-like. He invited them all into the studio. He ordered a mountain of sandwiches and sodas and played them the entire album from start to finish. He wanted to see how "real" Americans reacted to his "plastic soul." They loved it.

💡 You might also like: Avatar the Last Airbender Jet: Why We Can't Stop Arguing About Him

Why it Still Rings True

So many artists today try to "pivot" genres, but it usually feels like a marketing ploy. With Bowie, it felt like a survival tactic. He was shedding a skin that had become too tight.

If you listen to "Win" or "Somebody Up There Likes Me" today, they don't sound like 1975. They sound like a blueprint for the next thirty years of pop and R&B. He took the "Sound of Philadelphia" and twisted it into something more paranoid and modern.

Getting the Most Out of Young Americans

If you’re just discovering this record, don’t just stick to the hits. You’ve gotta dig into the deeper cuts to see what Bowie was actually doing.

- Listen for the backing vocals: Pay attention to Luther Vandross on "Fascination." You can hear the beginnings of an R&B legend right there.

- Check out the lyrics to "Young Americans": It’s a cynical, beautiful look at 1970s America. "Ain't there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?"

- Watch the Dick Cavett performance: Bowie performed these songs on TV while clearly under the influence of... well, everything. It’s a fascinating, twitchy look at a genius at work.

The legacy of Young Americans David Bowie isn't just that it gave us "Fame." It's that it proved a British rock star could respect, dismantle, and reinvent American soul music without it becoming a parody. It paved the way for the "Berlin Trilogy" and everything that followed.

To truly appreciate this era, find a copy of the Gouster sessions—the original, funkier version of the album before Lennon got involved. It offers a raw look at what Bowie was originally chasing before the "Fame" phenomenon took over.

Actionable Next Steps

- Listen to the "Gouster" version: Seek out the Who Can I Be Now? (1974–1976) box set. It contains the original tracklist before Bowie swapped songs for the Lennon collaborations. It’s much more "soul" and less "pop."

- Explore Carlos Alomar’s Work: Check out his later collaborations with Bowie on Station to Station and Low. You'll see how the "Young Americans" rhythm section essentially built the foundation for Bowie's most experimental decade.

- Read the Lyrics: Print out the lyrics to the title track. It’s basically a piece of 1970s literature that requires several reads to fully grasp the social commentary.