You’ve probably seen the word on a fancy candle or a "Yuletide" greeting card and figured it was just a flowery, old-timey synonym for Christmas. It’s not. Not exactly, anyway. If you really want to get into the meaning of Yule, you have to look past the plastic tinsel and the department store sales. You have to go back to a time when the dark was actually scary.

Long before the world was electrified, midwinter was a precarious threshold. Yule was the hinge. It was a period of about twelve days where the Germanic and Nordic peoples basically sat in the dark, looked at the freezing horizon, and waited to see if the sun would actually come back. It’s a gut-level celebration of survival.

Most people today use the word interchangeably with the December holidays, but its roots are deep, tangled, and a little bit wild. It’s about the Winter Solstice. It’s about the "Wild Hunt" screaming across the sky. It’s about the weird, beautiful overlap between ancient pagan grit and modern festive cheer.

Where the Word Actually Comes From

Etymology is usually dry, but with Yule, it’s actually kind of cool. The word comes from the Old Norse jól and the Old English ġéol. Interestingly, it wasn't just a day. It was a whole month—or two. The months surrounding the solstice were known as Giuli.

Scholars like Rudolf Simek, a noted expert on Germanic mythology, point out that Yule was originally a sacrificial feast. It wasn't just about "being jolly." It was about tiwa, or the gods. Specifically, it was linked to Odin. One of Odin’s many names is Jólnir, which literally means "The Yule One."

Imagine a longhouse in Norway around 900 AD. It’s pitch black outside. You’ve slaughtered the livestock you can’t afford to feed through the winter. You’re drinking fermented ale and hoping the "All-Father" doesn't decide to carry your soul away during the Wild Hunt. That’s the original vibe. It was high-stakes.

The Solstice Connection: Why the Date Shifts

If you talk to a modern Heathen or a Wiccan today, they’ll tell you Yule starts on the Winter Solstice. In 2025/2026, that falls around December 21st. But historically? It was more flexible.

Before the Julian and Gregorian calendars messed everything up, the timing was tied to the lunar cycle. The historian Bede, writing in the 8th century, mentioned Mōdraniht or "Mothers' Night," which happened right around the start of the festivities. It was a time to honor female ancestors or deities.

Nowadays, we’ve flattened it out. We picked a date on the calendar and stuck to it. But the meaning of Yule is fundamentally astronomical. It marks the shortest day and the longest night of the year. After this point, the days start getting longer. The "Sun King" is reborn. It’s the ultimate "light at the end of the tunnel" metaphor, except back then, the tunnel was made of ice and starvation.

The Log, the Tree, and the Ham: It’s All Pagan

Ever wonder why we drag a dying coniferous tree into our living rooms? Or why we eat a massive ham?

💡 You might also like: Marc Jacobs for Marc: What Most People Get Wrong About the Comeback

The Yule Log is the big one. Traditionally, this wasn't a chocolate cake from a bakery. It was a massive hunk of oak or ash. You’d bring it in, decorate it with greenery, and douse it with ale or mead. The goal was to keep it burning for twelve days.

- The Ash: If you couldn't find oak, ash was the go-to because it's linked to Yggdrasil, the world tree.

- The Protection: People kept the charred remains of the log under their beds for the rest of the year. They believed it protected the house from lightning and fire.

- The Symbolism: The fire was a sympathetic magic trick. You’re making a small sun on your hearth to encourage the big sun in the sky to get its act together.

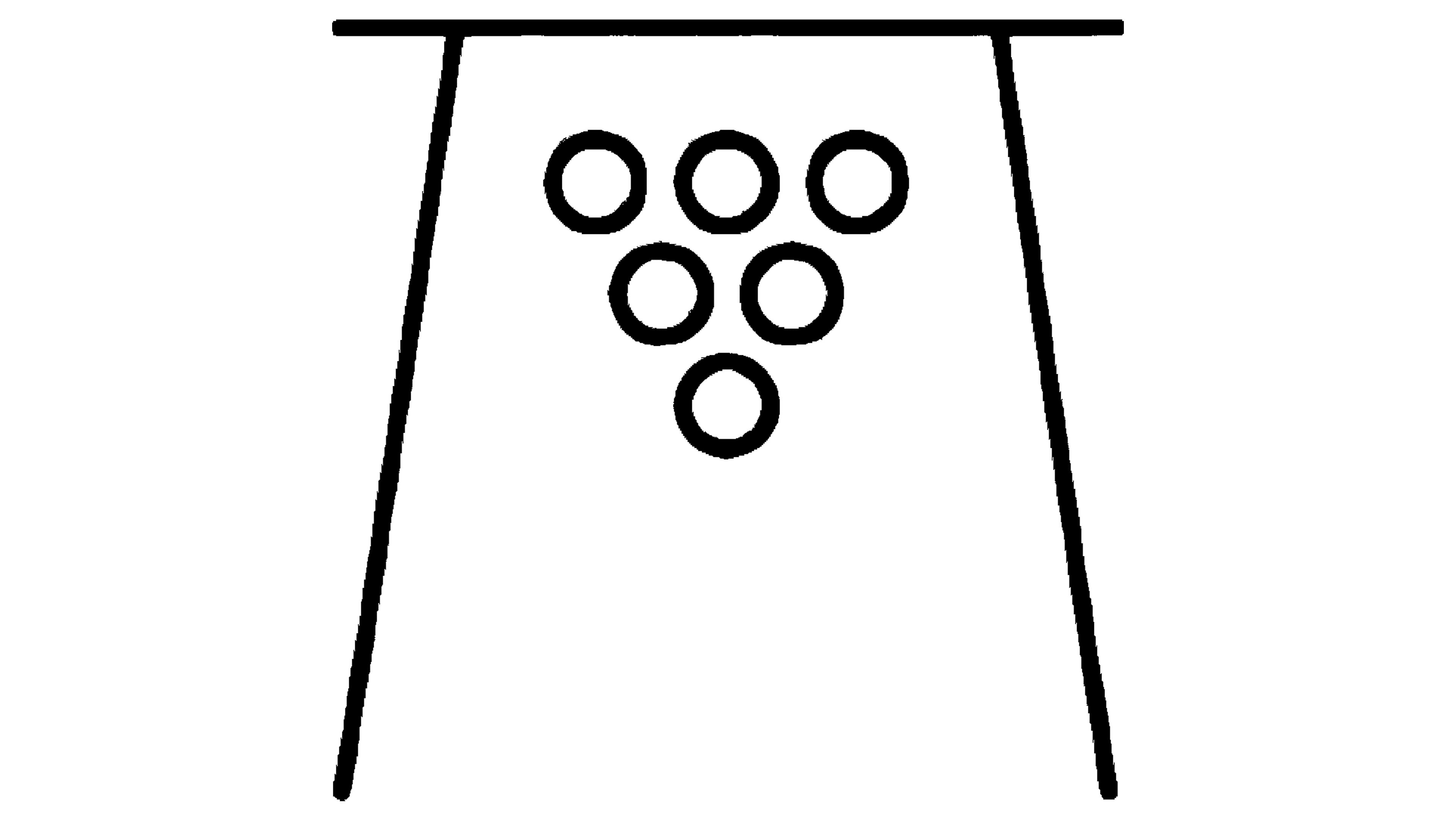

Then there’s the Yule Goat. In Sweden, you’ll still see the Gävlebocken, a giant straw goat. This traces back to Thor, whose chariot was pulled by two goats, Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr. The goat used to be the one delivering presents before a certain jolly fat man in a red suit took over the branding.

And the ham? That’s for Freyr. He’s the Norse god of fertility and sunshine, and his companion is a golden boar named Gullinbursti. Sacrificing a boar at Yule was a way to ensure the crops would actually grow once the snow melted.

How Christianity and Yule Collided

This is where things get spicy. A lot of people think the Church "stole" Yule. That’s a bit simplistic. It was more like a slow-motion cultural merger.

In the 10th century, King Haakon the Good of Norway, who was a Christian, passed a law. He mandated that the celebration of Yule should happen at the same time as the Christian Nativity. He basically told everyone: "You can still have your big party and drink your ale, but we’re doing it for Jesus now."

It was a brilliant PR move.

The festivities were so deeply ingrained in the Germanic psyche that the Church knew they couldn't just ban them. Instead, they "baptized" the traditions. The evergreen branches that represented eternal life in the face of winter became symbols of the eternal life of Christ. The candles stayed. The feasting stayed. The name even stayed in many languages.

The "Wild Hunt" and the Spooky Side of the Season

Honestly, we’ve sanitized the holidays way too much. The meaning of Yule used to include a healthy dose of terror.

During these twelve nights, the veil between worlds was considered paper-thin. This is when the Wild Hunt happened. Led by Odin or sometimes the goddess Berchta, a ghostly procession of hunters and hounds would scream through the night sky. If you were outside at the wrong time, you might get swept up in it and dropped miles away—or never seen again.

This is why people stayed inside. They drank. They told stories. They kept the fire bright. It wasn't just about being cozy; it was a defensive maneuver against the supernatural. Even the "Twelve Days of Christmas" is basically a ghost-story-filled remnant of this period.

Why We Still Care About Yule in 2026

You’d think in an age of central heating and seasonal affective disorder lamps, we wouldn't care about a prehistoric sun festival. But we do.

There’s a reason "hygge" became a massive trend. There’s a reason people still feel a weird, primal urge to put lights on their houses in December. We still have that ancestral memory of the "Long Night."

Modern Pagans and Wiccans have done a lot to revive the specific rituals of Yule. For them, it’s a "Sabbat." It’s a time for reflection. It’s about looking at the "shadow self" and deciding what you want to bring into the light in the coming year.

✨ Don't miss: The Love Language Type Test: What Most People Get Wrong About Modern Relationships

But even if you aren't religious, the meaning of Yule offers a better way to look at winter. Instead of seeing it as a miserable gap between autumn and spring, Yule frames it as a necessary pause. It’s the silence before the song.

Common Misconceptions (The "Actually" Section)

Let's clear some stuff up because the internet is full of "history" that people just made up on Tumblr in 2012.

- "Yule is just the 'Real' Christmas": Not quite. Christmas is a composite. It’s got Roman Saturnalia, Persian Mithraism, and Levantine Christianity mixed in. Yule is specifically the Germanic/Northern European contribution to that soup.

- "Holly and Mistletoe are only for Druids": While the Celts loved them, Germanic tribes used them too. Mistletoe was actually the thing that killed the god Baldur in Norse myth. It was later used as a symbol of peace—if you met an enemy under mistletoe in the woods, you had to lay down your arms for the day.

- "It’s always been about 12 days": The "12 Days" count actually varied. Some traditions saw it as a three-day feast. The 12-day thing became standardized much later, partly to bridge the gap between the lunar and solar calendars.

How to Lean Into the Meaning of Yule Right Now

If the commercialism of modern holidays makes you want to scream into a pillow, reclaiming a bit of the Yule spirit might help. It’s lower pressure.

Watch the Sunset

On the solstice, try to actually see the sun go down. Acknowledge that it’s the lowest point. It’s a bit of a psychological reset.

Bring the Outside In

Don’t just buy a plastic garland. Grab some real pine, some cedar, or some holly. The scent isn't just "festive"—it’s a reminder that life persists even when the ground is frozen solid.

The Silent Night

Try turning off all the lights for an hour. Sit by a fire or a single candle. Think about what you're leaving behind in the "dark" of the past year.

Feast with Intent

Instead of just eating until you're uncomfortable, make a meal that honors the season. Root vegetables, nuts, and yes, maybe some pork. Invite people you actually like.

The Actionable Bottom Line

The meaning of Yule isn't found in a history book or a store aisle. It’s found in the realization that the cycle always turns. No matter how dark it gets—literally or metaphorically—the sun is technically on its way back.

To bring this into your own life, start by identifying one "winter burden" you want to let go of. Write it on a piece of scrap wood and, if you have a safe place to do it, toss it in a fire. As that wood turns to ash, consider that the space it left behind is now open for the returning light.

- Audit your decorations: Swap one piece of plastic for something natural (pinecones, dried orange slices).

- Practice "Sun Waiting": On the morning after the solstice, try to catch the first light. It’s the "new" year in the most ancient sense.

- Tell a story: Not a movie, but a real story. Share a family memory or an old myth with someone. Keep the oral tradition alive.

Winter is long. Yule is the reminder that we don't have to just endure it; we can find a strange, flickering kind of joy in the middle of it.