You’ve seen it. That flimsy, laminated piece of paper taped to the wall of a doctor’s office. It looks like it belongs in the 1950s. Honestly, because most of the data behind it is nearly that old. We call it the healthy height and weight chart, but for most of us, it’s a source of pure anxiety. You step on the scale, the nurse slides the metal weight across the bar, and suddenly you’re told you’re "overweight" because you happen to have dense bones or a bit of muscle. It’s frustrating. It's often wrong.

Let's be real about what these charts actually are. They aren't a divine decree of how much you should weigh to be a "good" human. They are statistical averages. Most of the early versions were actually created by life insurance companies—specifically Metropolitan Life Insurance Company back in the 1940s—to figure out who was likely to die sooner so they could set premiums. They weren't looking at "health" in the way we do now; they were looking at actuarial risk.

The Problem With the Standard Metric

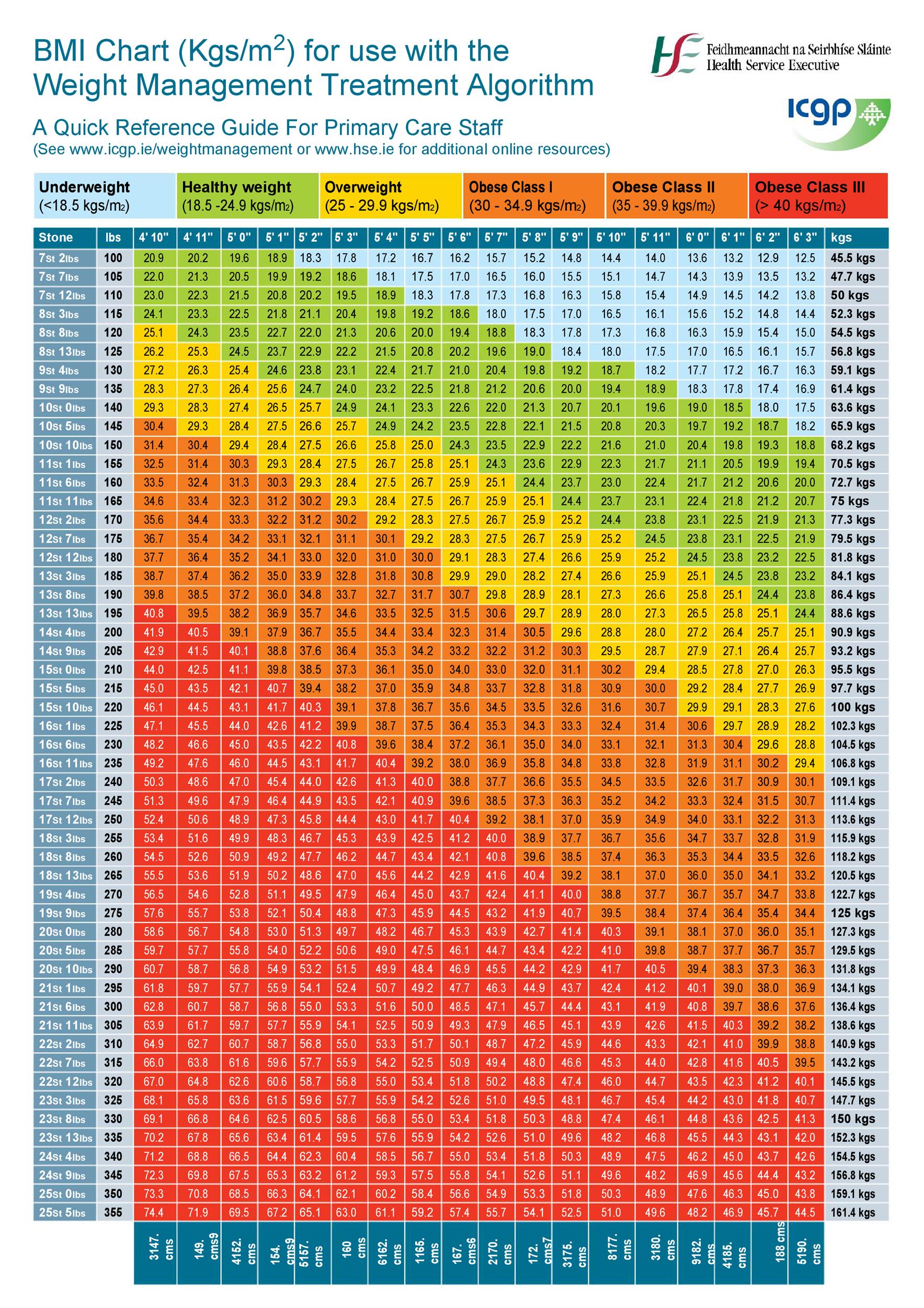

The Body Mass Index (BMI) is usually the engine behind any healthy height and weight chart you find online. Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian mathematician, came up with the formula in the 1830s. He wasn't even a doctor. He was a social scientist trying to define the "average man." He explicitly stated that BMI should not be used to judge the health of an individual, yet here we are, nearly 200 years later, using it as the gold standard in clinical settings.

It's a blunt instrument.

🔗 Read more: How Can You Tell If Your Pregnant Without a Test: What Your Body is Actually Trying to Say

BMI is just your weight in kilograms divided by the square of your height in meters. It doesn't know if that weight is marbled fat around your organs or the heavy quad muscles of a cyclist. For example, a 5'10" man weighing 200 pounds is technically "obese" on a standard chart. But if that man is a professional athlete with 10% body fat, the chart is effectively lying to him.

What the Numbers Actually Look Like

If we look at the CDC's general guidelines for adults, the ranges are pretty broad. For someone who is 5'5", the "healthy" range usually spans from about 114 to 150 pounds. That’s a 36-pound difference. Think about that. You could lose or gain the weight of a medium-sized dog and still be "normal" according to the government.

For a 6'0" person, the range jumps from 136 to 177 pounds.

But these numbers don't account for age. As we get older, our bodies naturally change. Some research, including a notable 2016 study published in The Lancet, suggests that for older adults, being slightly "overweight" on a BMI chart might actually be protective against frailty and certain diseases. It’s called the "obesity paradox." It sounds weird, but having a little extra cushion can sometimes be a literal lifesaver if you get hit with a serious illness that causes rapid weight loss.

Gender and Bone Density

Men and women are built differently. Obvious, right? But many simplified versions of the healthy height and weight chart don't emphasize this enough. Women naturally require a higher body fat percentage for hormonal health. If a woman's weight drops too low, even if she's in the "healthy" range on a chart, she might stop menstruating—a condition called amenorrhea. This can lead to bone density loss and long-term issues like osteoporosis.

Then there’s frame size. Some of us are "small-boned," and others are "large-boned." These aren't just excuses people make up at Thanksgiving. The width of your elbows and wrists actually dictates how much weight your skeleton is designed to carry. To find your frame size, you can wrap your thumb and index finger around your opposite wrist. If they overlap, you're likely a small frame. If they just touch, you're medium. If they don't meet, you've got a large frame. A large-framed person will always be at the top end of a healthy height and weight chart, and that is perfectly okay.

🔗 Read more: Fixing a no chin side profile: What actually works according to surgeons

Why Distribution Matters More Than the Total

If you really want to know if your weight is "healthy," stop looking at the total number and start looking at where it lives.

Abdominal fat—visceral fat—is the real villain here. This is the stuff that wraps around your liver and kidneys. You could be a "normal" weight on a chart but have a high waist-to-hip ratio, which puts you at a higher risk for Type 2 diabetes and heart disease than someone who is technically "overweight" but carries their weight in their hips and thighs.

Doctors are increasingly looking at Waist-to-Height Ratio (WtHR). The rule of thumb is simple: your waist circumference should be less than half your height. If you are 70 inches tall (5'10"), your waist should ideally be 35 inches or less. This is often a way more accurate predictor of health than any BMI-based healthy height and weight chart.

The Emotional Weight of the Scale

We have a weird relationship with these numbers. We let a piece of floor plastic determine if we’re going to have a good day or a bad day. But weight fluctuates. Daily. You can "gain" three pounds overnight just by eating a salty sushi dinner because your body is holding onto water. That isn't fat. It's just chemistry.

Even your hydration level changes the reading. Muscle glycogen holds onto water, too. If you’ve had a hard workout, your muscles might be inflamed and holding fluid to repair themselves. The scale goes up. You feel like a failure. In reality, you’re actually getting fitter.

Real-World Limitations

Let’s look at the "Asian BMI Paradox." Research has shown that people of South Asian descent often face higher risks of heart disease and diabetes at much lower BMI levels than Caucasians. For these populations, a "healthy" weight on a standard Western chart might actually be too high. The World Health Organization (WHO) has actually suggested lower BMI cut-offs for Asian populations because the standard healthy height and weight chart was developed primarily using data from people of European descent.

It’s a perfect example of why "one size fits all" is a dangerous lie in medicine.

Moving Beyond the Chart

If the chart is broken, what do we use?

- Blood Pressure and Blood Sugar: These are much better indicators of what's actually happening inside your pipes.

- Mobility: Can you walk up a flight of stairs without getting winded? Can you sit on the floor and get back up without using your hands? These are functional markers of health.

- Sleep Quality: Believe it or not, your weight and your sleep are a two-way street. Sleep apnea is often linked to weight, but poor sleep also messes with your hunger hormones (ghrelin and leptin), making you gain weight.

- Energy Levels: Do you feel like a zombie at 3:00 PM every day?

A Different Way to Measure Progress

If you're trying to get healthy, hide the scale for a month. Seriously. Put it in the attic. Use a piece of string to measure your waist once a week. Or just notice how your favorite pair of jeans fits.

The healthy height and weight chart is a map. But as the saying goes, the map is not the territory. You live in the territory. You know how your joints feel. You know if you’re eating enough greens or if you’re living on caffeine and stress.

Practical Next Steps for Your Health

Stop aiming for a "perfect" number on a chart that was designed for insurance companies in the 1940s. Instead, focus on these shifts:

🔗 Read more: Bottom Left Eye Twitching: Why Your Eyelid Won't Stop Jumping

- Measure your waist-to-height ratio. Grab a tape measure. If your waist is more than half your height, don't panic, but maybe start looking at your sugar intake and daily movement.

- Prioritize protein and fiber. These keep you full and help maintain muscle mass, which is what actually keeps your metabolism running.

- Focus on "Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis" (NEAT). This is a fancy way of saying "move more during the day." Pace while you’re on the phone. Take the stairs. It burns more calories over a week than a 30-minute gym session ever will.

- Check your labs. Ask your doctor for a full metabolic panel. If your triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and A1C are in the green, your weight might just be where your body wants to be.

- Build muscle. Especially as you age. Muscle is metabolically active tissue. The more you have, the more you can eat while maintaining a stable weight.

The goal isn't to be thin. The goal is to be durable. A healthy height and weight chart can give you a starting point, but your own body’s data—how you feel, how you move, and how your blood work looks—is the only chart that actually matters.