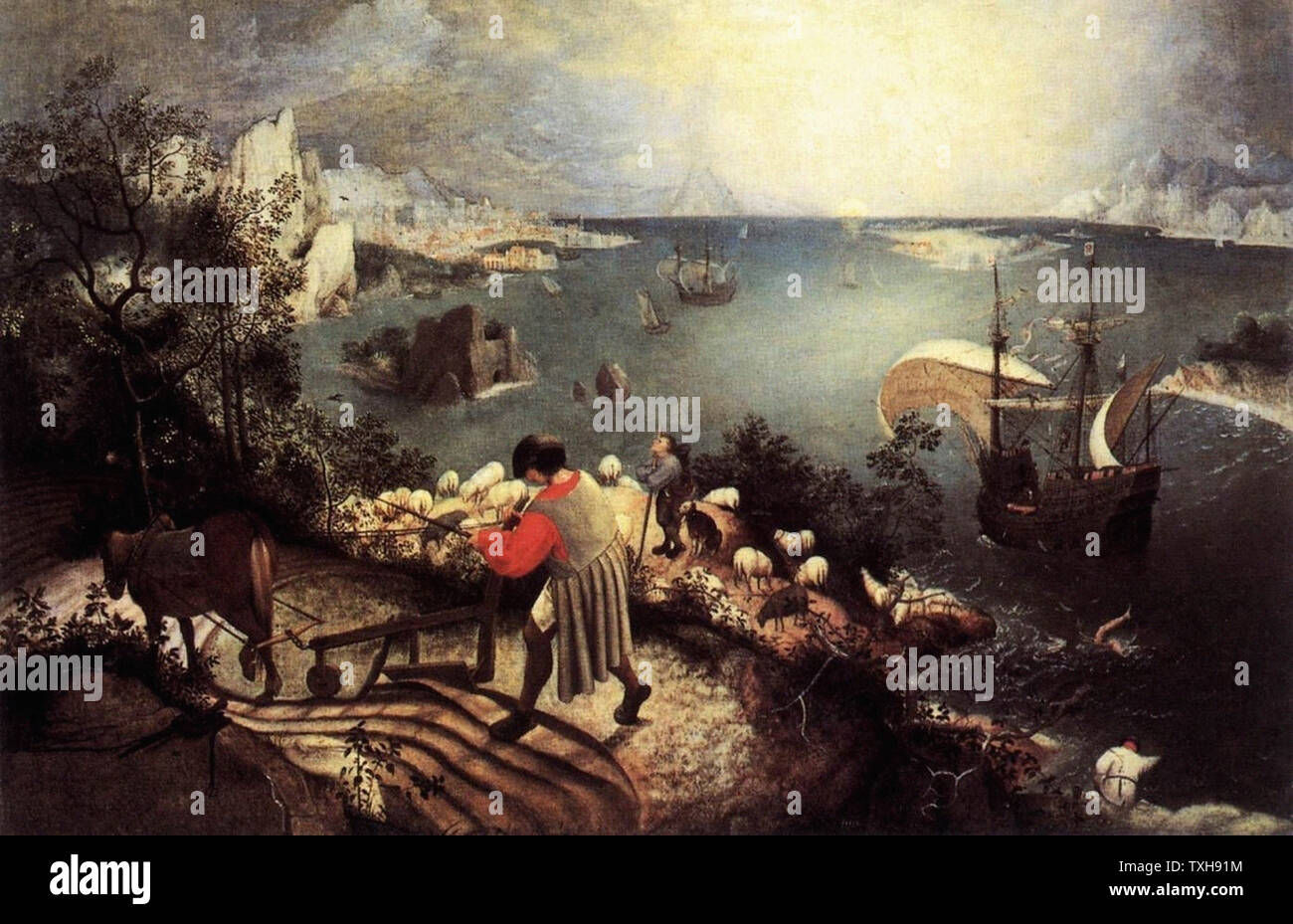

You’ve probably seen it in a textbook or scrolled past it on a "most famous paintings" list. A gorgeous, hazy coastline. A farmer pushing a plow. A ship with golden sails catching the light. And then, if you look at the bottom right corner, there’s this tiny, almost pathetic pair of legs splashing into the water.

That’s Icarus. The boy who flew too close to the sun. The guy who should be the hero of the story is literally a footnote in his own tragedy.

Honestly, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus is one of the weirdest, most frustrating, and deeply human pieces of art ever made. But here’s the kicker: it might not even be by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

The Mystery of Who Actually Painted This Thing

For a long time, everyone just assumed this was a Bruegel original. It has his "vibe"—the obsession with peasants, the massive scale, the "bird's eye" perspective. But around 1998, scientists got bored and decided to do some actual testing. They ran radiocarbon dating on the canvas.

The results? The canvas was made around 1600.

Bruegel died in 1569.

Unless he was painting from beyond the grave, he didn't touch this specific piece of fabric. Most experts now agree that the version hanging in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels is a very good copy of a lost Bruegel original. It’s like a high-end cover song. We know the "lyrics" are Bruegel’s, but the "performance" belongs to someone else—maybe his son, or a very talented workshop assistant.

Does that make it less valuable? Maybe to a billionaire collector, but for the rest of us, the message is still there.

Why the Ploughman Doesn't Care

The most jarring thing about Landscape with the Fall of Icarus isn’t the drowning boy. It’s the fact that nobody—and I mean nobody—is looking at him.

The ploughman is staring at the dirt. The shepherd is looking up at the sky, but he’s looking the wrong way (probably at Daedalus, who is actually missing from this version of the painting). The fisherman is too busy with his line.

There’s an old Flemish proverb that basically says, "No plough stops for a dying man."

That’s the core of the painting. It’s not about a mythological hero. It’s about the fact that while you are having the worst day of your life—while your dreams are literally melting and you’re drowning in the sea—the rest of the world is just trying to get through their shift.

It’s brutal.

But it’s also kind of a relief? There's a certain comfort in knowing that the world keeps spinning. The sun "shone as it had to," as W.H. Auden famously wrote in his poem about this very painting.

Look Closer: The Details You Missed

If you look at the bushes to the left of the ploughman, you might see something creepy. There’s a pale shape. Most art historians think it’s a corpse.

Seriously.

So you have a dead body in the woods and a drowning boy in the water, and this farmer is just... keepin' on. It reinforces that "life goes on" theme to a dark degree.

Then there’s the ship. It’s this "expensive delicate ship," as Auden called it. It’s right next to Icarus. The sailors must have seen him. They must have heard the splash. But they have "somewhere to get to." They’ve got cargo. They’ve got a schedule.

The Icarus Myth vs. Bruegel’s Reality

In the original Greek myth by Ovid, the ploughman and the shepherd are supposed to be "amazed" when they see Icarus and Daedalus flying. They’re supposed to think they’re seeing gods.

Bruegel (or whoever painted this) completely flips the script.

By making Icarus tiny and the peasant huge, the artist is making a statement about what actually matters. In the 16th century, people weren't obsessed with "main character energy." They were obsessed with survival. The farmer is the one providing food. The shepherd is the one watching the flock.

Icarus? He’s just a kid who didn't listen to his dad and wasted some perfectly good wax.

Why This Painting Still Hits Different in 2026

We live in an age of "look at me." We post our triumphs and our tragedies online, expecting the world to stop and notice.

✨ Don't miss: Antiperspirant spray for women: Why your morning routine might be failing you

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus is the ultimate reality check. It’s the 500-year-old version of being left on "read."

It teaches us a few things:

- Perspective is everything. Your personal catastrophe is usually a background detail to someone else.

- Duty is grounding. There is something noble about the ploughman just doing his job while the "gods" fall from the sky.

- Authenticity is complicated. Whether Bruegel painted it or not, the idea is what survived.

If you ever find yourself in Brussels, go see it. It’s smaller than you think. And when you see those little legs kicking in the water, remember that it’s okay if the world doesn't stop for you.

The sun is going to keep shining, the tide is going to keep coming in, and the ploughman is still going to have to finish that row.

How to Appreciate Art Like an Expert

If you want to dive deeper into this kind of "hidden detail" art, start looking at other Northern Renaissance painters like Hieronymus Bosch or Pieter Aertsen. They loved hiding the "important" stuff in the corners.

Next time you're at a museum, don't just read the little plaque and move on. Look for the person who isn't supposed to be there. Look for the splash.

Actionable Insight: Spend five minutes today looking at a "crowded" classic painting online. Don't look at the center. Look at the edges. You’ll be surprised at how much of the "real" story is hidden in the margins where the artist thought no one would notice.