You’ve probably seen the classic map of Polynesia islands in a geography textbook or on a grainy travel poster. It looks like a simple cluster of dots splashed across a blue background. Easy, right? Well, not really.

Most people think of Polynesia as a tiny vacation spot. In reality, it is a massive, sprawling triangle that covers roughly 16 million square miles of the Pacific Ocean. To put that in perspective, you could fit the entire continental United States, China, and most of Europe inside that triangle, and you’d still have plenty of water to spare.

It’s huge. It's empty. And it's incredibly complex.

The Massive Geometry of the Polynesian Triangle

If you want to understand the map of Polynesia islands, you have to start with the "Triangle." This isn't just a catchy name; it’s a geographical boundary defined by three massive anchors.

- Hawaii sits at the northern tip.

- Easter Island (Rapa Nui) marks the southeastern corner.

- New Zealand (Aotearoa) anchors the southwestern point.

Everything inside those lines is Polynesia. Everything outside—like Fiji, the Marshall Islands, or the Solomons—technically falls into Melanesia or Micronesia. Kinda crazy when you realize how close they are on a map, but the cultural and linguistic lines are sharp.

The land-to-water ratio is the first thing that messes with your head. Polynesia is about 99% water. The total land area is roughly 118,000 square miles, but here’s the kicker: New Zealand accounts for about 103,000 of that. If you take New Zealand and Hawaii out of the equation, the rest of the islands together wouldn't even cover the state of Vermont.

Why the Map Changes Depending on Who You Ask

Maps aren't just about rocks in the water. They're about people. While the "Triangle" is the standard definition, anthropologists talk about "Polynesian Outliers." These are islands like Rennell in the Solomon Islands or Kapingamarangi in Micronesia.

📖 Related: Idol Ridge Winery & Alder Creek Distillery: What Most People Get Wrong

They are geographically way outside the triangle.

But here’s the thing—the people there speak Polynesian languages and have Polynesian customs. So, if you're looking at a map of Polynesia islands through a cultural lens, the triangle starts to look a lot more like a spilled inkblot spreading across the Pacific.

Breaking Down the Major Island Groups

Honestly, trying to list every island is a fool’s errand because there are over a thousand of them. But we can group them into manageable chunks. Most of these fall under the umbrella of "French Polynesia," "Samoa," or "The Cook Islands."

French Polynesia: The Postcard Star

This is what most people picture when they close their eyes and think "Pacific Paradise." It’s actually five distinct archipelagos:

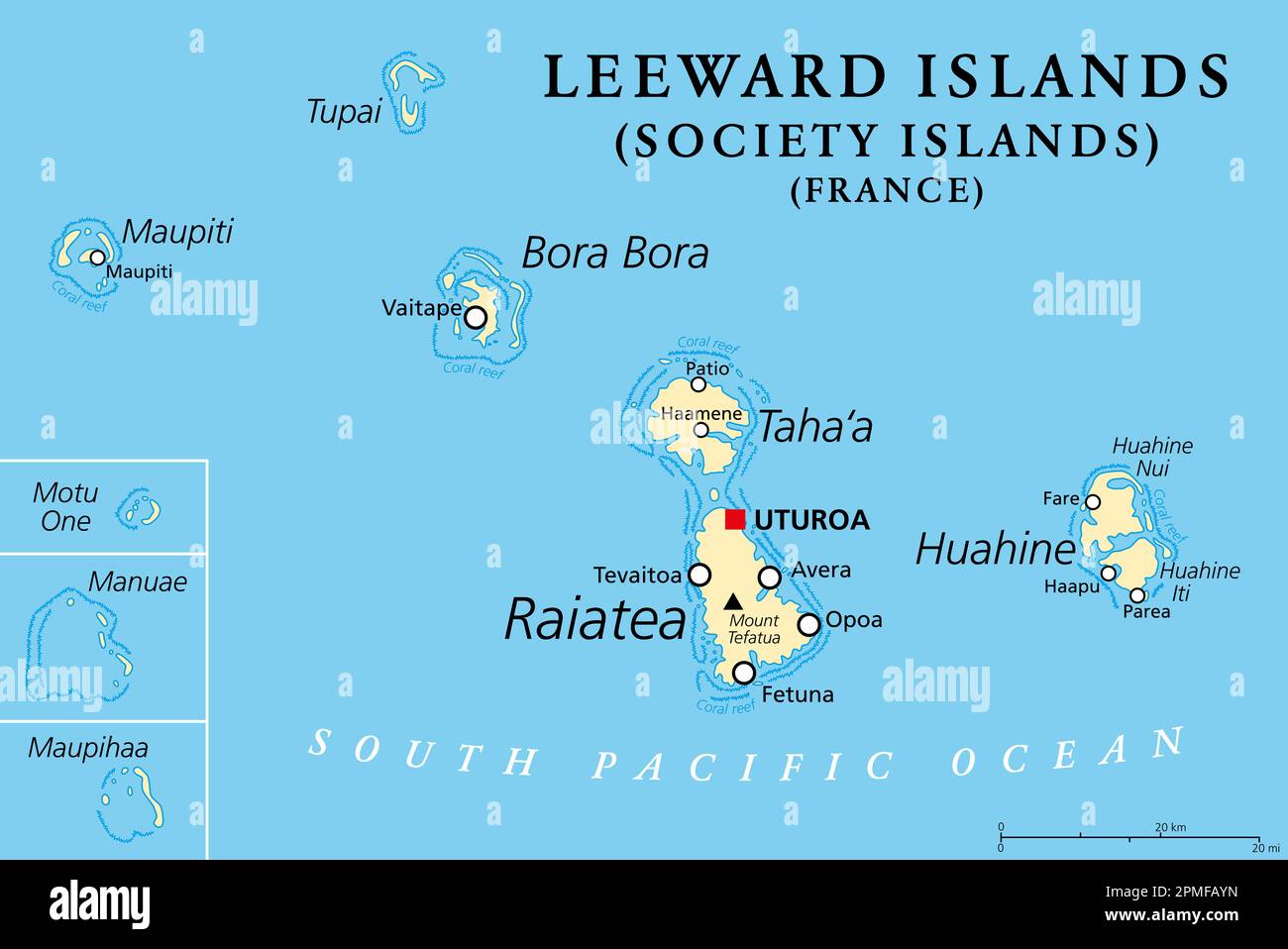

- The Society Islands: This includes Tahiti, Moorea, and Bora Bora. High volcanic peaks and turquoise lagoons.

- The Tuamotu Archipelago: These are low-lying atolls. Basically, rings of coral with a lake in the middle.

- The Marquesas Islands: Rugged, no reefs, and extremely remote.

- The Austral and Gambier Islands: Way down south, cooler, and much less visited.

Samoa and Tonga: The Cultural Heart

West Polynesia is often called the "Cradle of Polynesia." Samoa and Tonga are sovereign nations, unlike Hawaii (USA) or Tahiti (France). In Tonga, they still have a monarchy—the last one in the South Pacific. The map of Polynesia islands in this region is dense with history; this is where the distinct Polynesian culture first began to separate from its earlier Lapita roots about 3,000 years ago.

The Cook Islands and Niue

The Cooks are basically the quiet cousins of Tahiti. Rarotonga is the main hub, and Aitutaki is famous for having a lagoon that rivals Bora Bora but with half the crowds. They are in "free association" with New Zealand, which is a fancy way of saying they use Kiwi dollars and have New Zealand passports but run their own show.

How Ancient Navigators "Mapped" Without Maps

Modern maps are digital. We have GPS. We have satellites. The ancient Polynesians had... birds.

And stars. And the feeling of the waves against the hull of a double-hulled canoe.

✨ Don't miss: Back Bay to Providence: Why the Train is Always Better Than the Drive

If you looked at a map of Polynesia islands 1,000 years ago, it wouldn't be on paper. It was a mental map. Navigators used "wayfinding." They didn't just look at the stars; they memorized the "star path" for specific islands. If a certain star rose at a certain point on the horizon, they knew that sailing toward it would eventually hit Tahiti.

They also watched the birds. White terns and noddy terns fly out to sea to fish in the morning and return to land at night. If you’re a navigator and you see a tern at 4:00 PM, you just follow it. It’s literally a living GPS arrow pointing to land.

They even read the "reflection" of islands in the clouds. A high volcanic island like Moorea creates a distinct green tint on the underside of clouds that can be seen from miles away, long before the island itself clears the horizon.

Geology: Hotspots vs. Continental Fragments

Not all dots on the map of Polynesia islands are created equal.

Most of the islands—Hawaii, Samoa, the Society Islands—were formed by "hotspots." Essentially, there's a weak spot in the Earth's crust, and as the Pacific Plate slides over it, volcanoes poke through. It’s like a conveyor belt of islands. This is why the islands in a chain get older and more eroded the further you move from the active hotspot.

New Zealand is the weirdo. It’s not a volcanic hotspot creation. It’s actually a fragment of a "lost continent" called Zealandia. About 94% of Zealandia is underwater, leaving New Zealand as the biggest chunk sticking out.

Then you have the atolls. These are basically the "ghosts" of volcanic islands. After millions of years, a volcano sinks back into the ocean, but the coral reef that grew around its edges keeps growing upward. You're left with a ring of sand and palm trees surrounding a lagoon where a mountain used to be.

Travel Reality: Getting Around the Map

Let’s be real for a second. Looking at a map of Polynesia islands and actually traveling between them are two very different things.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: The Map of Maine Coastal Towns Most Tourists Miss

Because the distances are so vast, "island hopping" isn't really a thing like it is in Greece or the Caribbean. You can't just take a 20-minute ferry from Samoa to Tahiti. That’s a 1,500-mile flight, and honestly, you’ll probably have to fly through Auckland or Honolulu to get there.

Travel in Polynesia is expensive and logistically a bit of a nightmare. But that’s also why it stays so pristine. In 2026, many of these islands are leaning harder into "regenerative tourism." They don't just want your money; they want you to leave the reef better than you found it.

The Future of the Polynesian Map

Climate change is the elephant in the room. When you look at a map of Polynesia islands, you’ll notice a lot of those dots are Tuvalu or the Tuamotus. These are atolls that sit only a few feet above sea level.

As sea levels rise, the map is literally shrinking.

Some nations, like Tuvalu, are already looking at "digital twin" versions of their islands to preserve their geography and culture in the metaverse because the physical land might not be there in 50 years. It’s a sobering thought when you’re planning a trip to a "tropical paradise."

Actionable Insights for Your Next Step

If you're fascinated by the geography of this region and want to explore it beyond just a flat image, here is how to actually engage with the map of Polynesia islands:

- Use Bathymetric Maps: Instead of a standard Google Map, look for a bathymetric (undersea) map of the Pacific. It reveals the massive mountain ranges and "seamounts" that explain why the islands are where they are.

- Track the Hōkūleʻa: The Polynesian Voyaging Society often sails their traditional canoe, the Hōkūleʻa, using only ancient navigation. Tracking their route online is the best way to understand the scale of the Pacific.

- Check the Flight Hubs: If you are planning a trip, realize that the "map" is centered around three hubs: Honolulu (North), Auckland (South/West), and Papeete (East). All your travel plans will likely branch out from those three points.

- Support Local Mapping: Look into projects like the "Pacific Community (SPC)" which works on coastal mapping to help island nations prepare for rising tides. Understanding the vulnerability of these islands is just as important as knowing their coordinates.

The Pacific isn't just a space between continents. It’s a world unto itself, and the map is still being written by the people who call it home.