You’ve probably seen one before. A muscle diagram of the arm usually looks like a chaotic map of red fibers and white tendons, stripping away the skin to show what's happening underneath. Most people look at these diagrams and focus entirely on the biceps. It’s the "show muscle." It’s what you flex in the mirror. But honestly, if you're looking at a diagram to understand how your arm actually functions or why your elbow hurts after a long day at a desk, the biceps are often the least interesting part of the story.

The human arm is a mechanical masterpiece of levers and pulleys.

It's not just about "the guns."

Why Your Muscle Diagram of the Arm is More Complex Than You Think

When you first glance at a muscle diagram of the arm, your eyes go straight to the upper arm. You see the Biceps Brachii and the Triceps Brachii. Simple, right? One pulls, one pushes. But that's a massive oversimplification that leads to a lot of gym injuries and ergonomic mistakes.

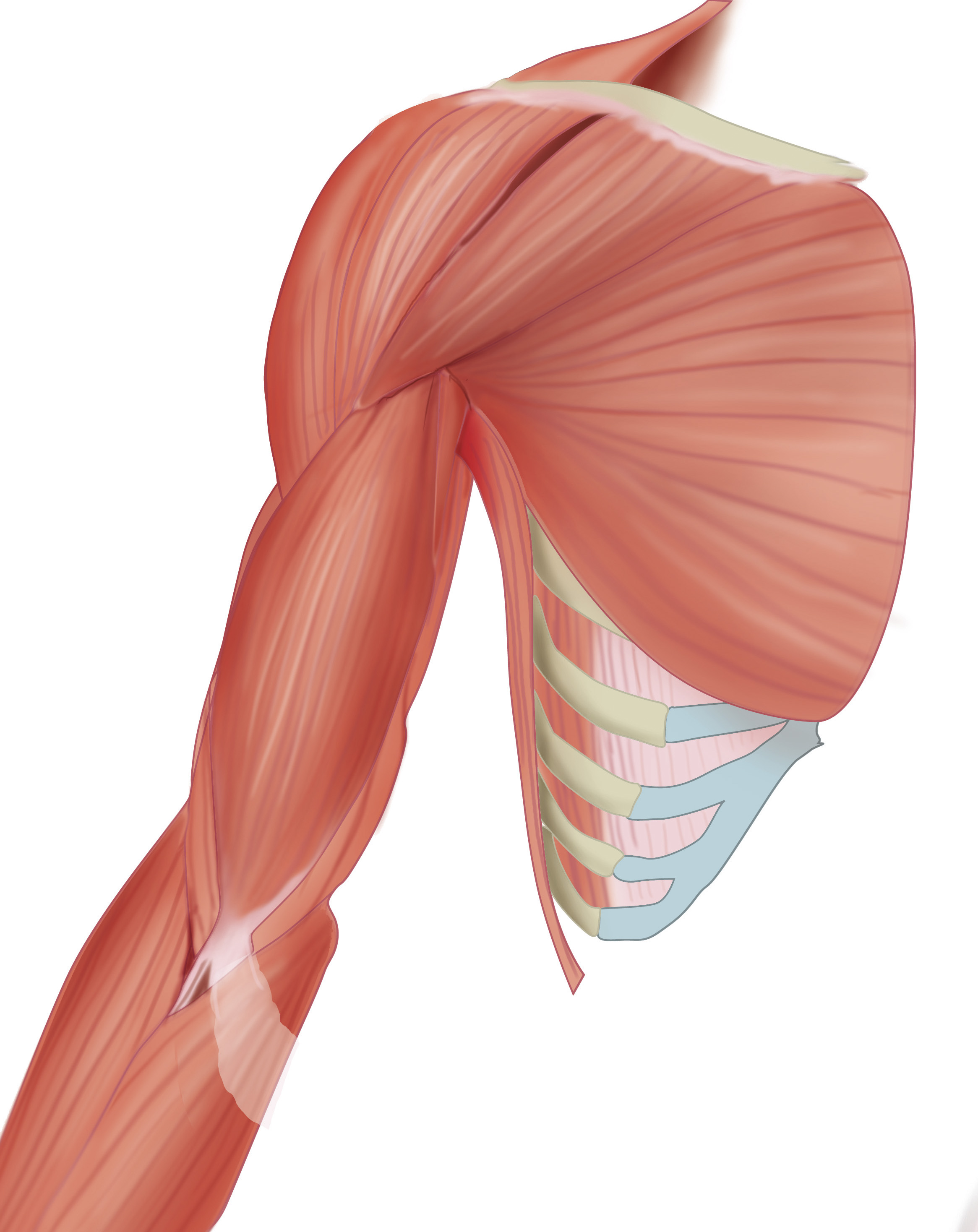

The arm is actually divided into "compartments" by tough connective tissue called fascia. In the upper arm, you have the anterior compartment (the front) and the posterior compartment (the back). The anterior side houses the biceps, but it also hides the brachialis. If you look closely at a high-quality anatomical chart, you’ll see the brachialis sitting deep—literally underneath the biceps. This muscle is actually the "workhorse" of elbow flexion. While the biceps gets all the credit, the brachialis generates more raw power when you’re lifting a heavy grocery bag or doing a pull-up.

Then there’s the coracobrachialis. It’s a tiny, slender muscle near the armpit. Most people ignore it. Yet, it's vital for stabilizing the humerus (the upper arm bone) against the shoulder socket. Without it, your shoulder would be incredibly unstable during overhead movements.

The Forearm: An Anatomical Jungle

If the upper arm is the "big picture," the forearm is where the real complexity lives. Look at any detailed muscle diagram of the arm and you’ll notice the forearm has significantly more muscles than the upper arm. Why? Because your hands are capable of incredibly fine motor skills.

We’re talking about roughly 20 different muscles.

These are split into the flexors (the palm side) and the extensors (the back of the hand side). Most of these muscles don’t even stay in the forearm; they send long, thin tendons down through the wrist and into the fingers. This is why you can feel the underside of your forearm moving when you wiggle your fingers. It’s like a puppet show where the puppeteer is located inches away from the puppet.

One muscle often misidentified is the Brachioradialis. It’s that thick muscle on the thumb-side of your forearm. Even though it's technically a forearm muscle, it actually crosses the elbow joint to help flex the arm. It’s the bridge between the two halves. If you have "tennis elbow," you're likely dealing with inflammation where these extensor muscles attach to the lateral epicondyle—the bony bump on the outside of your elbow.

Understanding the "Push-Pull" Relationship

Muscle diagrams usually show muscles in a static state, but they never work alone. They work in pairs. This is known as antagonistic pairing.

When you perform a bicep curl, the biceps is the "agonist" (the one doing the work). But for that movement to happen smoothly, the triceps—on the back of the arm—must be the "antagonist" and relax. If both contracted at the same time with full force, your arm wouldn't move; it would just shake.

The Triceps: The Unsung Hero

Actually, the triceps makes up about two-thirds of the muscle mass in your upper arm. If you’re looking at a muscle diagram of the arm because you want your arms to look bigger, you should be focusing on the three heads of the triceps:

- Long Head: Starts at the shoulder blade (scapula).

- Lateral Head: On the outside of the arm.

- Medial Head: Hidden deeper toward the midline.

The long head is unique because it crosses two joints—the shoulder and the elbow. This means its position changes based on whether your arm is over your head or down by your side. This is a level of nuance that basic diagrams often miss.

Real-World Application: Why This Matters for Your Health

Knowing where these muscles are isn't just for bodybuilders or med students. It’s about longevity.

Take "Golfer’s Elbow" (medial epicondylitis). This isn't a bone problem; it's a muscle and tendon problem. It happens when the flexor muscles on the inside of your forearm get overworked and pull on the bone. If you look at your muscle diagram of the arm, you’ll see that all those flexors converge into a single spot on the inner elbow. Knowing this allows you to target your recovery. You don't just massage the elbow; you have to release the tension in the entire forearm "belly" of the muscle.

👉 See also: Calculate Due Date Based on Ovulation: Why It Is More Accurate Than Your Last Period

The Role of the Deltoid

Wait, is the shoulder part of the arm? In a functional sense, yes. The deltoid is the "cap" of the shoulder and it’s divided into three distinct sections: anterior (front), lateral (side), and posterior (back).

A common mistake in reading these diagrams is thinking the arm starts at the shoulder joint. In reality, the muscles of the arm are deeply integrated with the torso. The Pectoralis Major (chest) and Latissimus Dorsi (back) both attach to the humerus. This means when you do a "chest press," you are heavily involving the triceps, and when you do a "row," you are using your biceps. You can't isolate them perfectly because the body doesn't work in isolation.

The Fascia Factor

One thing a standard muscle diagram of the arm almost always leaves out is the fascia. Fascia is a web of connective tissue that wraps around every muscle fiber, every bundle, and the entire muscle itself. Think of it like a thin, slippery sausage casing.

When people feel "tightness" in their arms, it's often the fascia getting sticky or dehydrated, rather than the muscle itself being short. This is why "myofascial release" (using a foam roller or a lacrosse ball) can feel so much better than a traditional stretch. You're un-sticking the layers so they can slide over each other.

Actionable Steps for Better Arm Health

Looking at a diagram is the first step toward "proprioception"—the sense of your body's position in space. Here is how to use that knowledge:

- Identify Your Weak Points: Hold your arm out. If your wrist hurts when typing, look at the "extensor" group on the top of your forearm in the diagram. Those are likely the culprits. Take a break every 30 minutes to stretch those specific tendons by gently pulling your fingers toward the underside of your wrist.

- Balance Your Training: If you spend your time doing curls (flexion), you must spend equal time on tricep extensions (extension). An imbalance in the arm muscles is a fast track to chronic elbow pain because one side is constantly "tugging" on the joint more than the other.

- Massage the Brachialis: Next time your bicep feels tight, try poking around the side of your arm, between the bicep and tricep. You'll find a hard, knotty muscle—the brachialis. Massaging this can often relieve "bicep pain" more effectively than massaging the bicep itself.

- Neutral Grip Matters: Many people find that pulling movements (like rows) hurt their elbows. If you look at how the muscles attach in a diagram, you'll see that a "neutral grip" (palms facing each other) puts the Brachioradialis in its strongest position and takes the strain off the tendons at the elbow joint.

The human body isn't a static image on a page. It's a living, breathing system of tension and compression. By understanding the layout provided by a muscle diagram of the arm, you move from just "moving your body" to actually "operating your machine" with precision. Whether you're trying to lift heavier, type without pain, or just understand why your shoulder clicks, the answers are written in the anatomy.

Start by palpating your own arm as you look at a diagram. Feel the tendons move. Notice where the muscle "belly" ends and the tough cord of the tendon begins. That physical connection between the image and your own body is where true anatomical literacy begins.