You're standing in the El Yunque rainforest, sweat dripping down your neck, squinting into a dense canopy of emerald green. You've been told this is the spot. This is where you find the Puerto Rico birds everyone posts about on Instagram. But honestly? All you hear is the rhythmic, deafening "co-qui" of the tree frogs and the rustle of wind. You might see a flash of red, but by the time you raise your binoculars, it's gone. Most people come to the island, do the big tourist hike, and leave thinking they've "done" the birding scene. They're wrong. Totally wrong.

The reality of birdwatching in Puerto Rico is that the island is a compressed explosion of biodiversity, but it's picky about where it shows off. We aren't just talking about seagulls at the beach. We’re talking about 17 endemic species—birds found nowhere else on this entire planet—living in ecosystems that range from bone-dry cactus deserts to misty cloud forests. If you want to see the good stuff, you have to stop acting like a tourist and start acting like a local biologist.

The Endemic Holy Grail: Beyond the Parrot

Most people know about the Puerto Rican Parrot (Amazona vittata). It’s the poster child for conservation. It’s also nearly impossible to see in the wild unless you know exactly which managed release site you're hovering near. For a long time, these guys were down to just 13 individuals. Thirteen! Thanks to the Luquillo Aviary and the Rio Abajo State Forest programs, they're bouncing back, but they aren't exactly hanging out at the San Juan Marriott.

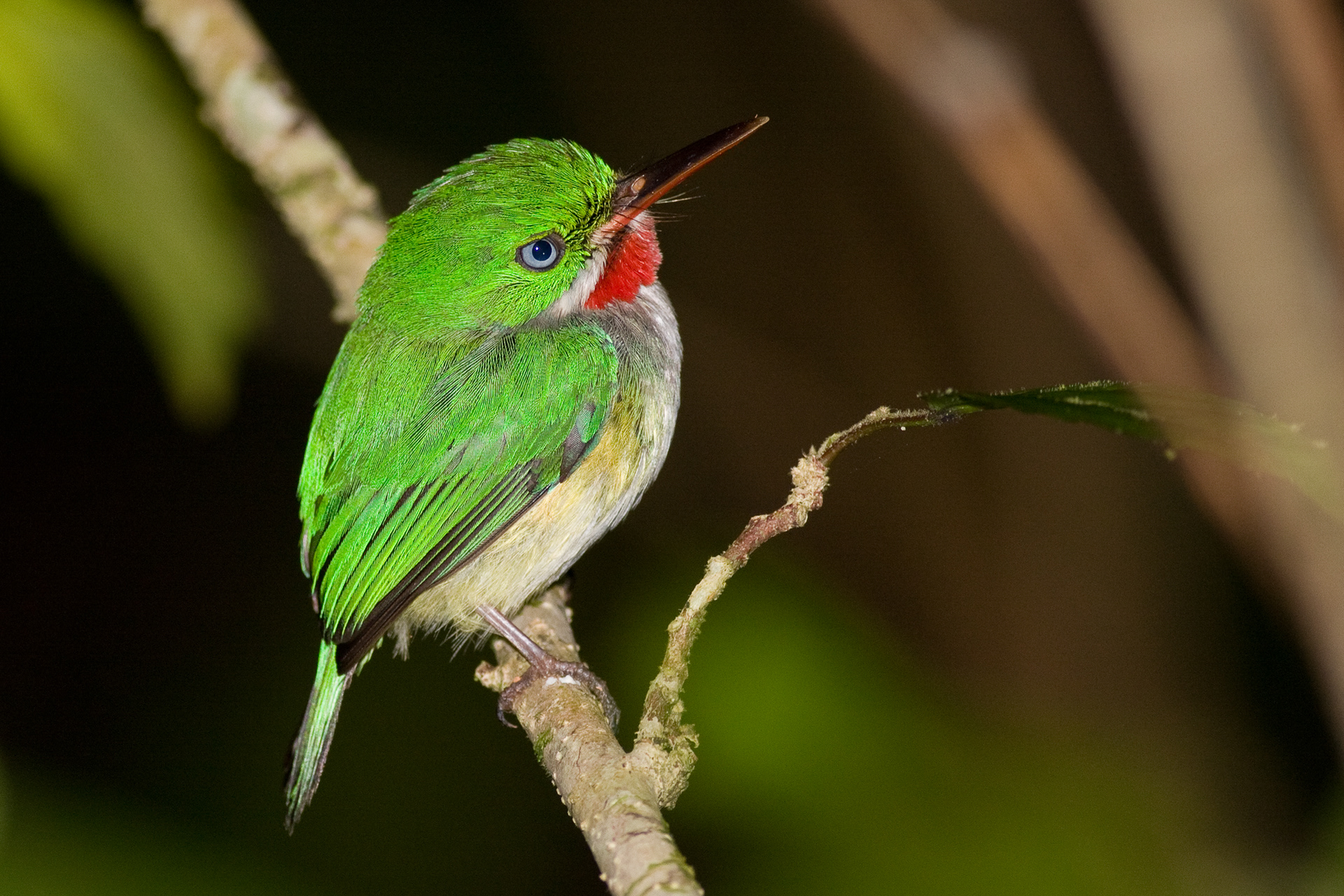

If you actually want to see Puerto Rico birds that define the island's soul, you look for the Puerto Rican Tody, or the San Pedrito.

It’s tiny. Think of a lime-green cotton ball with a bright red throat and a beak that looks slightly too big for its body. These birds are fascinating because they don't just nest in trees; they burrow into mud banks like miniature kingfishers. If you walk along the trails in the Guajataca Forest and stay quiet—really quiet—you’ll hear a sharp beep sound. That’s him. He’s sitting on a branch, dead still, waiting for an insect to fly by. You’ve probably walked past ten of them without realizing it. They are remarkably chill around humans once you spot them, often letting you get within a few feet before they even think about fluttering away.

The Night Shift: Finding the Guabairo

Puerto Rico has a ghost. It’s called the Puerto Rican Nightjar (Antrostomus noctitherus). For decades, people thought it was extinct. Gone. A footnote in a textbook. Then, in the 1960s, someone realized that the weird whistling "whip-poor-will" sound coming from the dry forests of the south wasn't a mistake. It was the Nightjar.

This bird is the ultimate test of a birder’s patience. It lives in the Guanica Dry Forest—a place that feels more like Arizona than the Caribbean. They have perfect camouflage. They look like a pile of dead leaves. You won't see them during the day. You have to go at dusk, deal with the heat, and listen for that haunting, repetitive call. It’s a specialized experience. It’s not for the casual hiker who just wants a selfie. It’s for the person who wants to see a survivor that beat the odds of extinction.

Why the Southwestern Coast is the Real MVP

Forget the rainforest for a second. If you want volume, you go southwest. Cabo Rojo is the spot. Specifically, the Salt Flats (Las Salinas).

The Salt Flats look like a different planet. The water is pink because of the brine shrimp and algae, and the ground is crusted with white salt. This is a massive pit stop for migratory shorebirds. If you're there during the winter months, you’ll see thousands of Semipalmated Sandpipers, Stilts, and Plovers.

But the real prize here is the Yellow-shouldered Blackbird.

It’s endangered, mostly because of shiny cowbirds laying eggs in their nests—brood parasitism is a nasty business. The Yellow-shouldered Blackbird is sleek, black, with a flash of brilliant yellow on the wing. They hang out near the mangroves and the scrubland. Honestly, they look a bit like a standard red-winged blackbird you’d see in a Kansas cornfield, but the rarity makes the sighting hit different.

- Pro Tip: Hit the Birdwatching Tower at the Cabo Rojo National Wildlife Refuge.

- Warning: There is zero shade. You will bake. Bring more water than you think you need.

- Timing: Get there at 6:30 AM. By 10:00 AM, the birds are hiding from the heat, and you should be too.

The Misunderstood "Trash Birds"

Every region has birds that locals ignore. In the States, it’s pigeons or sparrows. In Puerto Rico, people sometimes overlook the Bananaquit (Reinita Mora).

Don't be that person.

📖 Related: Why the G Line Matters: Everything to Know About the Los Angeles Metro Orange Line

The Bananaquit is a tiny, curved-beak nectar-thief with a bright yellow belly and a white "eyebrow." They are everywhere. They will literally try to steal sugar off your table if you're eating breakfast outside in Rincon. They’re bold, they’re loud, and they’re technically the official bird of Puerto Rico (though some argue it’s the Stripe-headed Tanager). Their nests are these messy globes of grass and string that they build in the most inconvenient places, like hanging flower pots or ceiling fans.

Then there’s the Gray Kingbird, or Pitirre. You’ll see them perched on power lines. They are incredibly aggressive. There is a famous saying in Puerto Rico: "Cada guaraguao tiene su pitirre." It basically means every hawk has a kingbird that harasses it. These tiny birds will dive-bomb red-tailed hawks ten times their size just to get them out of their territory. It’s peak "big bird energy" in a small package.

The Complexity of the Coffee Plantations

One of the coolest things about Puerto Rico birds is how they’ve adapted to the island's agriculture. Traditionally, coffee was grown under the shade of massive trees. This "shade-grown" coffee created a secondary forest canopy.

The Puerto Rican Emerald hummingbird loves these spots.

But as farmers move toward "sun coffee" (high-yield, no trees), the birds are losing their homes. When you buy coffee in Puerto Rico, look for the brands that support bird-friendly practices. You’re not just buying a caffeine fix; you’re paying for the habitat of the Puerto Rican Bullfinch—a chunky black bird with a rufous-colored crown and throat that sings like a flute.

If you visit a plantation like Hacienda Pomarrosa in the mountains near Ponce, you’ll see the difference immediately. The air is cooler, the birds are louder, and the ecosystem feels alive. You’ll likely spot the Puerto Rican Woodpecker there, too. It’s the only woodpecker endemic to the island. It has a bright red throat and breast, and it spends its day hammering away at the trunks of shade trees. It’s a steady, rhythmic sound that becomes the soundtrack of the Cordillera Central.

✨ Don't miss: Weather in Downtown LA: What Most People Get Wrong

The Controversy of the Escaped Parrots

Now, if you’re in San Juan, you’re going to see parrots. Bright green ones. Loud ones. These are NOT the endangered Puerto Rican Parrots.

They are mostly Monk Parakeets and Orange-winged Amazons that escaped from the pet trade or were released during hurricanes. They’ve formed massive colonies in urban parks. Some locals love them. Some ecologists hate them because they compete with native species for food and nesting holes.

It’s a weird, modern reality of island birding. You’ll be sitting in a traffic jam in Santurce and see a flock of twenty parrots scream overhead. It feels tropical and wild, but it’s actually a sign of a shifting ecosystem. It’s a reminder that islands are fragile. One hurricane, like Maria in 2017, can wipe out decades of conservation work in a single afternoon. In fact, Maria decimated the fruit trees that many endemics rely on, forcing birds like the Scaly-naped Pigeon to find new ways to survive in the aftermath.

Practical Steps for Your Birding Trip

If you're serious about seeing these birds, you can't just wing it. Puerto Rico's terrain is rugged, and the birds are localized. Here is exactly how you should plan your route to maximize your sightings of Puerto Rico birds.

1. Secure the Right Gear

Don't bring your heavy, long-range spotting scope if you're hiking El Yunque; the humidity will fog it up, and the density of the trees makes it useless. Bring a pair of 8x42 binoculars. They offer a wide enough field of view to catch the Tody before it moves. Also, download the Merlin Bird ID app, but specifically download the "Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands" pack before you leave your hotel. Cell service in the mountains is a joke.

2. The Early Bird Rule (Literally)

In the tropics, the "dawn chorus" is everything. By 9:30 AM, the activity drops by 70%. If you aren't at the trailhead by 6:30 AM, you're just taking a walk in the woods. This is especially true for the Puerto Rican Screech Owl (Múcaro). If you want to see one, you need to be out at 5:00 AM in the secondary forests near Arecibo. They have these big, expressive eyes and a call that sounds like a descending whinny.

3. Target the Hubs

Focus your itinerary on these four distinct zones to see the widest variety of species:

- El Yunque National Forest: High altitude, wet. Good for the Puerto Rican Tanager and the Elfin-woods Warbler (which was only discovered in 1971!).

- Guanica Dry Forest: Dry, scrubby. Essential for the Nightjar and the Adelaide's Warbler.

- Cabo Rojo Salt Flats: Coastal, salty. Best for shorebirds and the Yellow-shouldered Blackbird.

- The Central Cordillera: Coffee country. Great for woodpeckers, bullfinches, and hummingbirds.

4. Hire a Local Guide

Honestly, this is the best move. People like Sergio Colon or the guides from local conservation groups know the specific trees where the birds nest. They can hear a faint "chip" and tell you exactly which species it is. Supporting local guides also puts money back into the island's economy, which incentivizes the protection of these habitats.

5. Be Mindful of the Weather

Hurricane season (June to November) isn't just a threat to your flight; it changes bird behavior. Post-hurricane birding is often easier because the canopy is thinner, but it’s heartbreaking to see the birds struggling for food. February to April is generally the "sweet spot" for birding—the weather is cooler, the migratory birds are still there, and the endemics are starting their breeding seasons.

🔗 Read more: Maui Weather: What Most People Get Wrong About the Temperature

Birding in Puerto Rico isn't about checking boxes on a list. It’s about understanding the resilience of an island that has been battered by storms and development but still managed to keep its unique feathered inhabitants alive. When you finally see that tiny green Tody or hear the call of the Nightjar in the dark, you realize you're witnessing something ancient and incredibly precious. Pack your boots, get some DEET, and get out there. The birds are waiting, but they won't come to you. You have to go find them.